I was born in 1996.

When I was 4, my dad bought a computer on finance. It cost him £1200 over a two year period, and by today’s standards was pretty shit. Specs aside, it was probably the best headstart I could ever receive in life.

Every day after school I would boot up the machine, and surf the web.

Every time I would boot up this machine I was preparing for an adventure. What would I learn on YouTube that evening? Which Wikipedia rabbit-hole would I wind up in? What software would I torrent? (spoilers: it was Photoshop, thanks Adobe!)

The Internet I know today is a very, very different place.

The Internet is a place, and we’re always there

I had more friends URL than IRL. Depressing as it may be, I wasn’t a very popular kid. I was one of few coloured kids in a very white neighbourhood, in a very white school. The Internet was a place I went not just to learn, but a place I went to exercise an exciting and novel kind of freedom. My computer was my car, and every night I could drive away to hundreds of different cities, each with their own rules and cultures. That bit is important. It’s indicative of something quite ‘Human’. We seek out and gravitate towards places that accept us, our ideologies and our identities. The Internet in some way shape or form helped me find all of the people and places that are most important to me now, and I’m sure I’m not the only one.

Over the course of my life I’ve watched the Internet gradually move in some welcome directions:

- More integrated and accessible: the way I interact with the web is primarily mobile, and I’d be willing to wager that’d be the same for you too

- Powerful: the capabilities of the Internet (as a platform) are vastly superior to what I grew up with

It also moved in some less positive directions:

- More centralised: 31% of all traffic on the internet points at AWS data centres

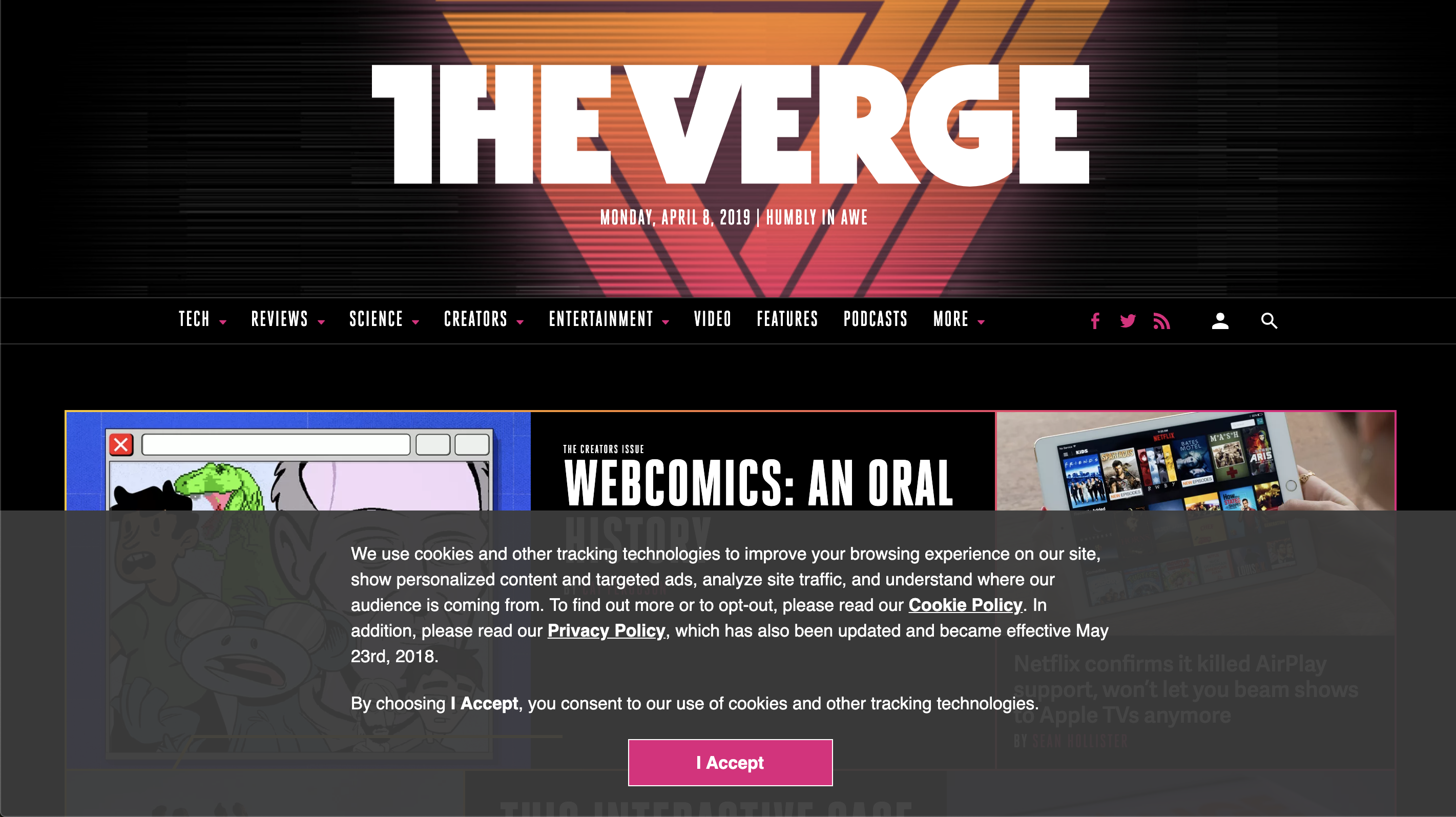

- Disgusting: I’ll talk about this more later, but we’ve got a real littering problem in our cities. I guarantee you’ll see one of the following today: pop-ups, notification requests, feature-walls and cookie banners… Gross, gross cookie banners.

Love him or hate him, Elon Musk made a point a while back about how we’re already cyborgs. We’re wired into this place via the smartphones in our pocket. When your phone buzzes it has the same salience as someone tapping you on the shoulder. When you run out of battery you slowly begin to feel that dreaded FOMO.

The Internet is a place. We’re always there. And it’s our responsibility to look after it.

But… We fucked it

I’m a pretty firm believer in the Internet being both a Proper Noun, and the most important technological advance humanity has ever made. But we fucked it.

A brief history of how we fucked it from my perspective:

The Internet first became publicly accessible on August 6 1991. We began building our own cities (sometimes GeoCities), our own spaces. We tried to get some real-estate.

Then in the mid 2000s, Silicon Valley began building bustling, virtual metropolitan cities in the form of Facebook, Twitter, etc. We all began leaving our GeoCities and decided to live over there instead. It had a better economy on the surface. The caveat of course is that Facebook and your GeoCity used two different kinds of currency.

Then Facebook fucked democracy, so we started talking about our data.

While all that was happening, the first proposal for a more powerful data protection act was making its way through the EU.

Cookie banners were the first sign of an Internet on its decline. There’s more insidious stuff behind them. And other kinds of distractions altogether. Tracking technologies became more sophisticated, browsers began asking us for notifications, and pop-ups decided to come out of retirement.

Our cities became poorly kept and intensely surveilled - all in the name of collecting data to then hook us back into The Feed, to then sell us things we so desperately needed. The Web of today is not the one of openness, exploration and excitement - it’s become a horrible machine, and the machine is creating value for its shareholders.

We were once explorers. Now we’re slaves to opaque power structures that siphon our data and follow us everywhere we go.

Let’s talk briefly about GDPR (sorry)

Whilst I’d recommend a read of this infamous piece of regulation, the truth is it’s quite boring. So here’s the takeaway that I care most about:

- GDPR isn’t about cookies, but cookies can contain identifiable information

- GDPR requires anyone processing any kind of identifiable information to ask for consent to process this data

My interpretation is that GDPRs implicit end goal was to give a ‘Subject’ (you), some sense of sovereignty and control over the data that could be used to change your experience of a product, to sell you things, or to get you to vote an Actual Baboon into presidency.

With that in mind, there are a few things I can do as a designer on this crusade to clean up the internet.

‘Business needs’

Before we can start talking about how to design interruptions well, let’s get this one thing out of the way. The only ‘business need’ there is is money. They want your data, because it’s essentially a convertible note that’ll, through some means, turn into cold hard cash.

This manifests itself as business turning to dark patterns to try and get your ‘consent’.

For example, some of our competitors, will give a business the option to assume a scroll event on a webpage is consent. Gross.

Exploiting the aesthetic-usability effect to design interruptions well

If my house caught fire and I could only take one thing, I’d take the book ‘Universal Principles of Design’. The book outlines an ever-growing set of principles that are considered evolutionary predispositions in relation to design. One of these principles is the aesthetic-usability effect - it describes a paradox that people perceive more aesthetically pleasing designs as much more intuitive (even if they aren’t), than those considered to be not aesthetically pleasing.

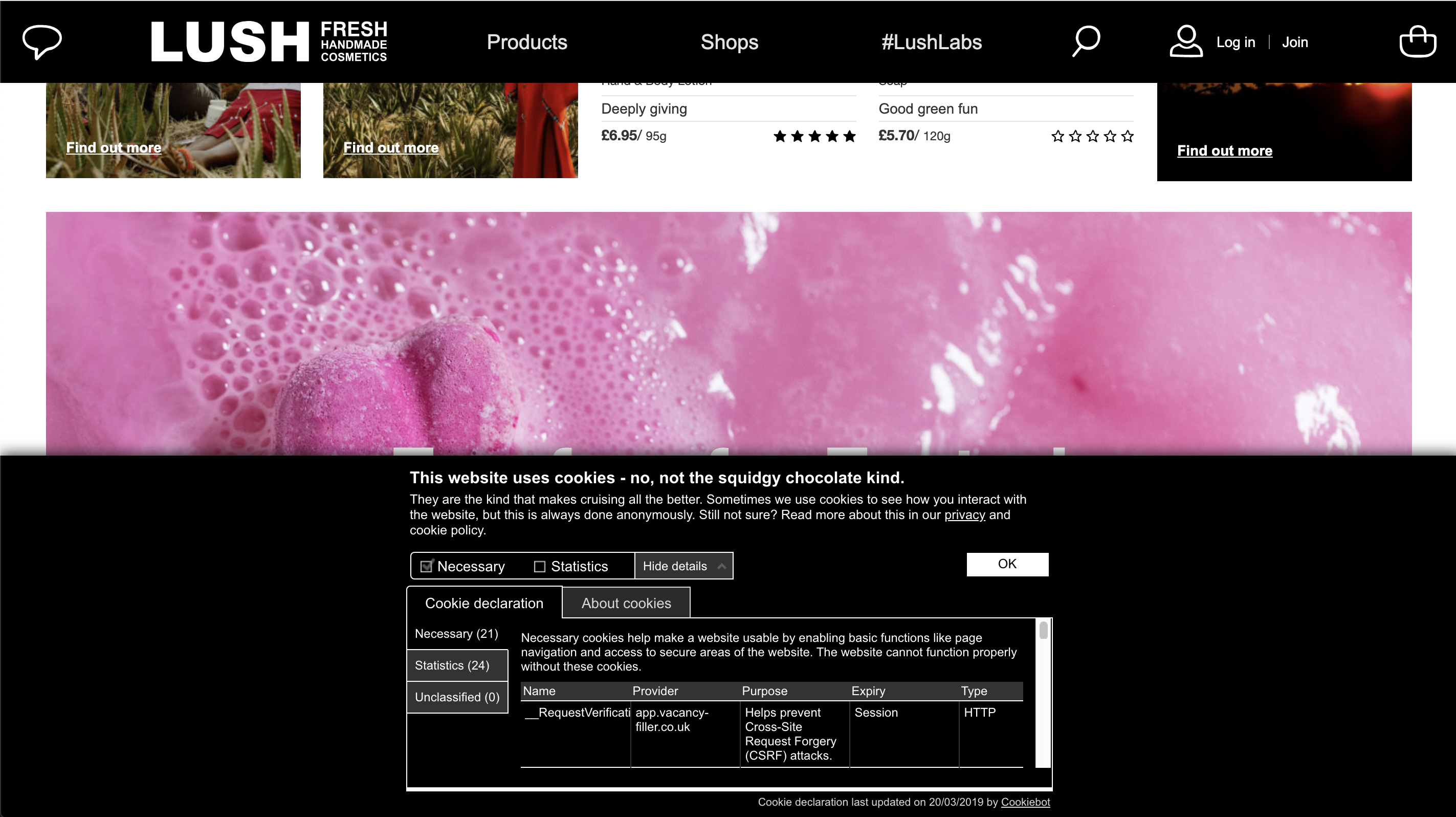

Fortunately for me though, the bar isn’t very high.

50% of screen real-estate spent on this shit. Acknowledge me. Please.

We took a simpler approach. Stop trying to be funny with your copy, stop overwhelming the user, give them a tl;dr and some options:

No. It’s not a cookie banner. And it’s going to become so much more.

Converting dark patterns into lighter patterns by injecting them with transparency

If a business relies on tracking technologies to make money, they really don’t want you to be able to opt-out of cookies. So they model their cookie banners after a needy ex-partner: they just want to be acknowledged - and they’ll send you about 42 texts to make sure you interact with them.

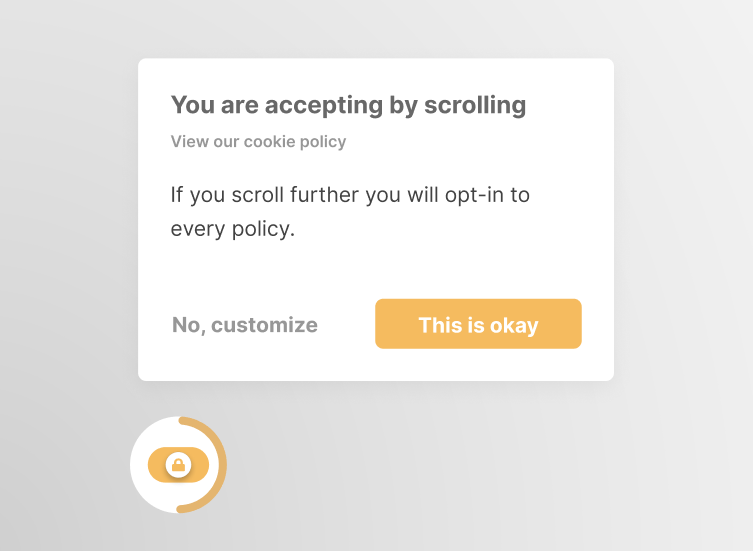

If you don’t interact with a banner however, you wind up with businesses still trying to get that data using more nefarious means. One popular GDPR solution called OneTrust allows businesses to ‘scroll to consent’.

In design we call these dark patterns.

Dark patterns are ways by which some asshole designer or developer somewhere might design an interface that tricks you into making a decision. Scroll to consent probably takes the cake as my least favourite, but if a business needs it… Who am I to say no? Gotta keep feeding the machine, right?

I don’t think I have a problem with this kind of practice, if you want scroll to consent, go for it — but if you’re going to use our product, we’ll for sure let the user know. Our version of scroll to consent is transparent, and obvious:

The ball is going to drop on businesses using dark patterns. An example of how you’ll lose trust by deploying these dark arts is Facebook. Only recently Facebook began prompting users to increase their account security using 2FA. To set up 2-factor authentication, they needed your phone number. Awesome. Account on lock.

Wrong.

They then began, by default, allowing other Facebook users to look you up using your phone number that you’d provided for 2FA.

If a business wants you to consent via scroll so they can drop their cookies as soon as you interact with the site, they should feel free to do that. They should just keep you in the loop at all times.

I wish I could have written more words on this, but at this point I’m running out of CoherenceCoin.

This is just a sneak peak at some of the stuff I’m working on, and this is all subject to change. It’s early days. Though if you’d like to help me answer these questions and clean up the internet, get in touch with me via Twitter and I’ll be more than happy to answer any questions!