There’s an ugly, complex, tangle of common misconceptions about your data that I will now explain to you so please pay attention.

After GDPR the likes of Facebook and Google were all like “woo power to the people, you all own your data now!”

Haha, great. Except not, because: they’re wrong.

Not wrong because they’re doing something which results in you not owning your data - but wrong because what they are saying is impossible. There is literally no such thing as ‘your data’ and ‘owning it’. Consider these easily digestible facts about you: your name, when you were born, and how tall you are. Quick-fire, let me explain:

- Your name: sorry, other people are called that. It’s not yours; you don’t own it.

- Your date of birth: duh, other people were born that day too, so…

- Your height: I think you know the answer to this.

I imagine you’re shouting the following words at your screen: “well what do I own then? Do I even own my shoes?” Yes, you own your shoes, silly. They are possessions that you paid for and they are not data.

Think about it this way: your name, age, and height is not your data. It is data about you. Same goes for your shoe size, your heart rate, the colour of your hair (we all know that you can’t own a colour unless you’re Anish Kapoor and we don’t like him, so…).

Right so that’s the first step in destroying this very dangerous idea that you now ‘own your data’. Let me just - once more - quickly translate this inaccurate and misleading language into the truth:

Your data = data about you.

Owning it = [blank space]

Let’s call ‘data about you’ what it actually is

Nowadays there’s all kinds of data out there about you. It comes in large amounts and it’s very detailed. Never mind for a moment how it got there and who’s using it. We’ll get to that. For now, forget about you, and consider this person I just made up called April.

April works at RGB Time, an art gallery in Soho. She often meets up with old uni friends after work and they go to Noodle Town, the hippest noodle joint that ever did noodle. On the weekends she visits other art galleries like the Tate and secretly wishes she worked there instead because RGB Time are terrible. She does yoga every Tuesday morning. She plays football every Sunday afternoon. She goes out in Dalston.

So there you go, we know a bit about April now. The fact that she does yoga and likes noodles is all data about her. And this is the day to day habitual stuff. Some actually refer to this as ‘personal data’. But I don’t think that’s descriptive enough either.

The fact April plays football and does yoga on the same morning every week is not personal information. It’s behavioural. Therefore, we can (and should) call it behavioural data. So that’s… data about behaviour. Can you own a behaviour?

BONK. What was that? Oh that was just the sound of a hammer hitting a nail on the head. That means something important happened. The important thing that happened is this realisation: don’t be silly, of course you cannot own a behaviour.

This means that, not only does ‘your data’ not exist (because it’s actually behavioural data), you also have no ownership over it (because, again, it’s behaviour).

The term ‘personal data’ should be reserved for basic things like your name, age, and gender. And coupled with behavioural data, you get something very powerful indeed…

Behavioural data is just a computery guessing game…

Now it’s time to look outside of April’s world. The stuff we know about her is fairly superficial, and on it’s own it’s nothing and it’s boring. What about all the people who are like April? They also like noodles and do yoga and maybe even work in an art gallery. Collective behavioural data is where things start to get interesting (or scary - depends how you look at it). Allow me to explain.

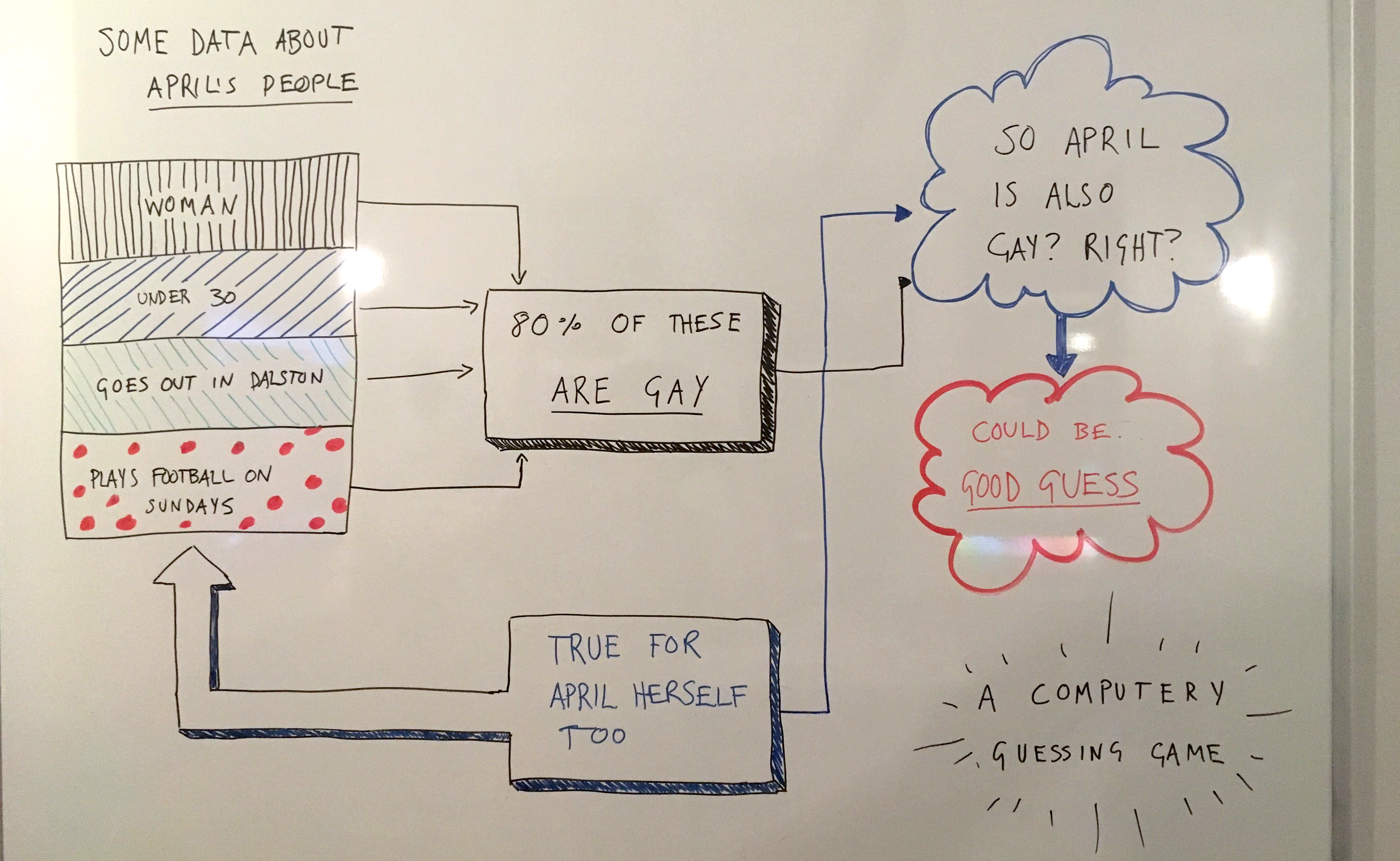

Let’s take some of the other stuff about April that we learned earlier. She plays football on Sundays and goes out in Dalston. There are a bunch of other people like April who also do these two things. Let’s narrow down this cross-section of people by using some personal data about April: her age and gender. She is a woman under 30.

Okay, so, here’s the thing - the majority of these people like April who: play football on Sundays, go out in Dalston, are a woman, and are under 30… are also gay. Therefore, if you are a computery thing (technical term) looking at data about April, it would be very easy to infer that April is also gay.

BONK. Oh, ha there’s that sound again. Must be something important. The important thing that happened is that I just inferred something about April. There’s nothing out there to suggest that she is gay - that was literally just a guess, based on the piles of behavioural data out there about her (and people like her).

You damn sure can’t own data that was inferred. This kind of data is a product of your existence in the digital age. The other thing about guessing is, sometimes it’s wrong. Weird to take ownership over information that isn’t even accurate, don’t you think?

So the power lies in matching personal data with large amounts of behavioural data:

Collective behavioural data on people like April + Personal data about April herself

=

a chance to fill in the gaps with educated guesses.

+++Wooo let the computery guessing games begin+++

The harder I guess, the harder I do profits

Right okay so all this data about what April does on a day to day basis is painting a picture of who she is. Who is this picture for? Duh, businesses who want to sell her things. With the data they hold - or have access to - they can do lots of powerful things like show April targeted ads and, you know, guess her sexuality.

But why is this useful and why are they guessing? Glad you asked. Types faster and harder

Please remember that you, just like April, are a consumer. Most of the time, vendors are just finding cool new ways to get you to consume. If they don’t know what you like they will not let that stop them - they will just guess what you like. Just look at this really awesome business model:

- Learn about the humans and identify their wants and desires

- Find or make products which fulfil those wants and desires.

- Advertise products to the humans, sell products to the humans.

- Jess Bezos can now have another super yacht - the status quo is maintained.

The problem with this model is not that it’s totally fictionalised to help you understand my point. It’s that there is a secret key step between 1 and 2. As we’ve learned, identifying wants and desires can be done by inferring. Doing this instead of just using actual facts is done for two reasons: it’s easier than asking, and you can guess things that you ‘aren’t allowed’ to ask.

For example, imagine ASOS asking you your sexual orientation before checking out - that just wouldn’t work. But what if ASOS already have enough data about you to just take a guess? Exactly. They do have enough data about you, and they are guessing.

How did all these businesses get all this data in the first place?

Duh, because we gave it to them. It’s really quite simple; every time you use Facebook or Twitter or ANYTHING you, sort of, ‘implicitly agree’ that they can share the data you generate with whoever they want, and as a result our society is under constant surveillance which means-

Oh yeah wait it’s actually devastatingly and unnecessarily complex. What a world. The large collections of behavioural data out there are fed in a number of ways - cookies are one big way. I won’t go into detail about that here, because there are other articles that cover it.

Behavioural data is a valuable resource.

Quick, name another resource: oil? Yep that’s a resource.

And what’s one of the biggest problems with oil? It’s going to run out.

What’s the difference between oil and data?

Data will never run out because all we do is produce it. If you delete all the world’s data today we’d probably be fine because we’d just make more quite easily. We probably wouldn’t be fine actually - please do not attempt to delete all the world’s data.

What I’m getting at here is the next step in our wholesome journey of demystification: looking at data as a resource. And resources have value. But only to the right people. Oil has no value to an individual consumer, but central heating does.

So one of the issues we have here is that we do not value the data that we produce in the same way that big business does. Makes sense, why would you? There’s nothing you can do with it, and everything about you, you already know.

UNBONK. What was that? That was the sound of a hammer NOT hitting a nail on the head (sorry, I don’t know what sound that makes, if any. ‘Unbonk’ will have to do). The notion that you can’t do anything with the behavioural data that you produce is inaccurate. Individuals can actually extract value from this data, but business are making it really hard. This is because controlling access to the data also controls the value.

Since GDPR came out (like a hit single 😉), companies have to let us make data requests. This is where you say ‘hey gimme all that data that I’ve produced by using your product’, and then they send you some files. Companies have leveraged this legal requirement by using it to demonstrate that you have some ownership over this data. That is, yet again, extremely misleading. Surely if you owned it, you wouldn’t have to ask for it?

So once again I will ask you to forget about ownership. Just forget it. Stop remembering it forever. And now start thinking about access.

Just look at this real-world example of someone trying to get their data from Spotify so they can use it in a new account. This is basically what happens when you try and request data from Spotify:

- They take like over a month to send it to you because processing data is SO HARD and SO BORING

- When you get it you realise:

- It’s only 250kb. Apparently all data you’ve produced this whole time has amounted to less than a megabyte? Okay…

- It’s in a .zip file and it’s like, several layers of awkward.

- When you try and move this data to a different service or even just different Spotify account, you can’t.

- You find a third-party tool to get this done

- The tool only really does half the job

- You marvel at the power bestowed upon you after having made this data request.

So if you make a data request from Spotify, the bundle of info you get is basically your search and streaming history, your playlists, everything else in your library, etc. You can’t use it in a new Spotify account. You can’t use it for another streaming service. You can’t do anything except look at it. It’s the exact same information you have access to when browsing around your Spotify app. Wow, so useful, so valuable, so cool.

As you can quite plainly see, this current model of data access is flimsy, useless, and shrouded in dishonesty. By allowing you access to the data you’ve produced, Spotify are technically being GDPR compliant, but is this useful to you?

They’ve heavily controlled the access to this data (look at this twitter thread to see what I mean), and therefore have not allowed you, the consumer, to extract any value from it at all. It’s like walking around with a badge that says ‘Hi, I’m April’ all the time. That’s nice, but why do you need to wear that?

It’s not about privacy, it’s about innovation

Okay ALSO why are you all so obsessed with ‘getting this data back’? Is it privacy? It’s privacy isn’t it? You’re worried about privacy. Good, you should be worried about that. But this isn’t the right way to worry about it.

Think back to Spotify: if you keep using it, you produce data about your music preferences, and Spotify uses this data to figure out what other music you might like. This is not an invasion of privacy. This is actually a good example of how you, as a consumer, do get some value from the data you produce (lest we forget that Spotify is a paid service… they have to at least make an attempt at being ‘of value’).

However, the problem with Spotifiy is that it appears to be completely dominating the world of music streaming, and is therefore one of the few decent choices out there (you’d have to pay me a lot of money to use Apple Music again. Sorry but that’s a no from me).

How has this nonsense happened? Because, as outlined above, when you make a data request from Spotify, the data you get is useless, and you can’t move it to another service. In other words, it’s not actually portable. People stick with Spotify because it’s just easier.

At the moment we get no value out of the data we produce as consumers, whereas businesses seem to be extracting a heap of value. And we keep producing data for them. If our access wasn’t so narrow, we could get a lot out of the data we produce too. If this data was more portable, other platforms may be able to use it to improve their services. Then you might get something that is like Spotify, but even better. Apply that to every other app and service out there and the world of tech might actually be hip and cool again instead of dark and evil.

Phew, how about a recap?

Yes recaps help us learn. So, as mentioned at the very beginning, Facebook and Google are peddling the line that ‘you own your data’. Let’s go over why this is bullshit:

‘Your data’ does not exist, it’s actually data about you

As we saw with April, she likes noodles and works in an art gallery. This is simply information about her, and it’s not helpful to say that she owns it. Eating noodles on a regular basis is a behaviour, therefore the data that exists about her is behavioural data. You can’t own a behaviour - you just can’t.

Behavioural data is used to infer things about you

If companies know who you are, and what demographics you fit into, they can quite easily guess more information about you. Why do they do this? To serve you more ads. Remember, April is a consumer and April is all of us. I mean, you really can’t own something that was inferred about you, can you?

Just because you’re good at guessing, doesn’t mean you’re right all the time

Some key information that was inferred about April on our journey is that she was gay. Is she? Dunno you’d have to ask April. But she might not know either. The internet may have inferred something about her sexuality before April inferred it herself. Ugh, what a weird proto-invasion of privacy…

Data is super valuable to everyone

But the only people who are able to truly extract that value are large companies who have all the data, and the resources to process that data. Consumers don’t get much out of the data that they keep on producing, because access to it is very narrow. That’s why we should stop talking about data ownership, and start talking about access.

Look, what if you used all this data not for evil?

Cool idea. If data wasn’t constantly being used to sell us more crap, maybe we’d have time to use it for something good? Yes…

What if we lived in a world where data was a bit more open and accessible? What would that look like? What if we lived in a world where all of this data was in one central place and we could get to it whenever we wanted?

Great questions, great questions. These are questions asked by everyone who wants to read part 2 of this article, where April slips into an alternate universe and we explore these ideas.