Our physical universe started from [what seems like] nothing. Over 13.8 billion years the system’s complexity increased — the creation of matter, the building of stars, the construction of solar systems and then, finally, the origination of life.

Now, within this complex system that is our physical universe, life seems to be creating a universe of its own. A digital universe.

Extraordinarily youthful in comparison to our physical universe, our digital universe has seen a remarkable evolution over the last 28 years. And this evolution has uncanny similarities to the evolution of our physical world. Matter, stars, solar systems, galaxies and black holes — versions of all of these exist in our digital world too.

But how did all of this happen? Let’s start with a very brief physics primer.

Stars in our physical universe form from clouds of dust and gas that lie in empty space.

Whilst dust and gas rest peacefully, something can change — perhaps a gravitational disturbance from a nearby supernova — causing some of the dust and gas within the cloud to pull together in clumps. As the clumps attain more mass, their gravitational pull increases — drawing more and more matter in in a vicious cycle.

Over the next million years, a clump continues to grow in size and temperature into a dense body called a protostar. At about 7 million degrees Celsius, nuclear fusion starts — turning hydrogen into helium. Material continues streaming into the protostar from its gravitational attraction, increasing its mass and temperature even further.

Eventually, the protostar (if big enough) has a massive release of gas, blasting other matter away from its fiery surface and leaving a shining star. The matter blasted away now starts forming new clumps which begin orbiting the star as planets.

This is, on a basic level, how a solar system is formed in our physical universe.

Our digital universe follows a remarkably similar story. Just with different physics and much smaller timescales.

Rewind about thirty years. The digital universe’s ‘big bang’ occurred in 1990 when the world wide web started. An entire universe was formed where information (text, images, audio, video, etc) now became interconnected in a single space — an information space.

The path into this new universe was the Internet. And for the next 10 years, entrepreneurs, scientists and corporations of all sizes explored our new universe and its potential value — what could it offer that we didn’t already have around us?

In the early 2000s, the value to individuals was beginning to be realised. Social media began. Companies like Six Degrees, Friendster and LinkedIn allowed us to redefine ourselves and connect with anyone else in this new universe via whatever identity we wanted. People flooded online in their digital form — data — to explore this new exciting universe.

Soon, our digital universe was no longer empty space, but an ever-expanding rich cloud of data about us.

The Facebook Star is born

In 2004, Facebook was started. Harvard University students began uploading simple data about themselves online — name, email, phone, interests, education, political views, relationship status, etc.

The once nebulous cloud of our data started to clump together around a single entity, Facebook.

A natural phenomena started to take place. Just like in our physical universe where heavier objects have larger gravity, something similar is true in our digital universe. The more people on Facebook, the greater the digital gravity pulling in more people and more data. We start posting what’s on our mind, what food we’re eating, where we’re going that day, pictures of our outings with family and friends, and even our real-time location. Thousands more people each day start doing the same thing.

When a clump of matter in our physical universe reaches a certain size and high enough temperature, chemical reactions start taking place. Notably, the fusion of hydrogen nuclei in to helium. This is the reaction that keeps the star alive — making it shine and preventing it from collapsing.

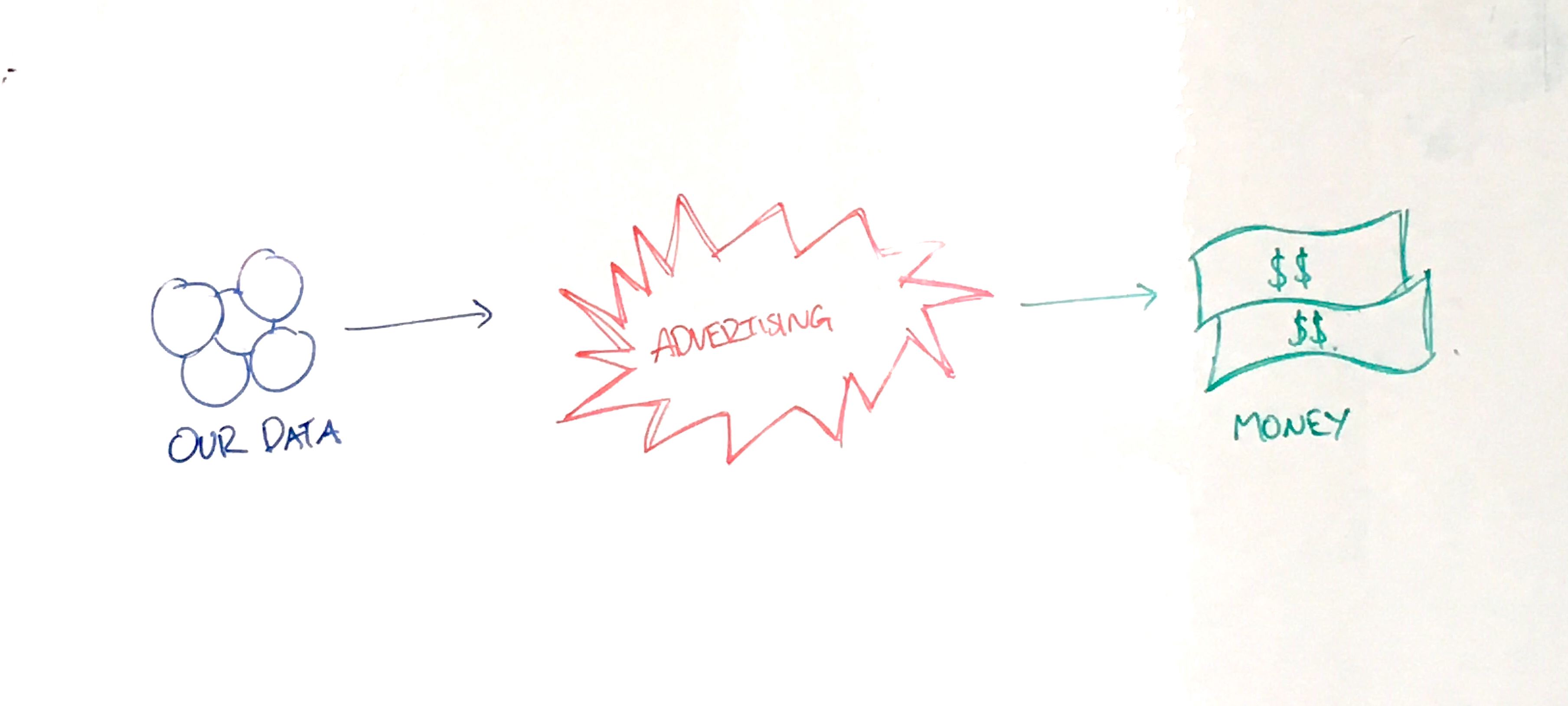

At this point in our digital evolution, Facebook has reached a similar stage. It has enough data and enough digital gravitational pull for chemical reactions to take place. Advertising.

A physical star burns hydrogen through nuclear fusion to create helium. A digital star burns data through advertising to create money.

With enough money coming out the other end, Facebook can prevent itself from collapsing by creating new features, engulfing other competing stars using its money (i.e. acquisitions like Instagram) and paying its employees to keep the operations running smoothly.

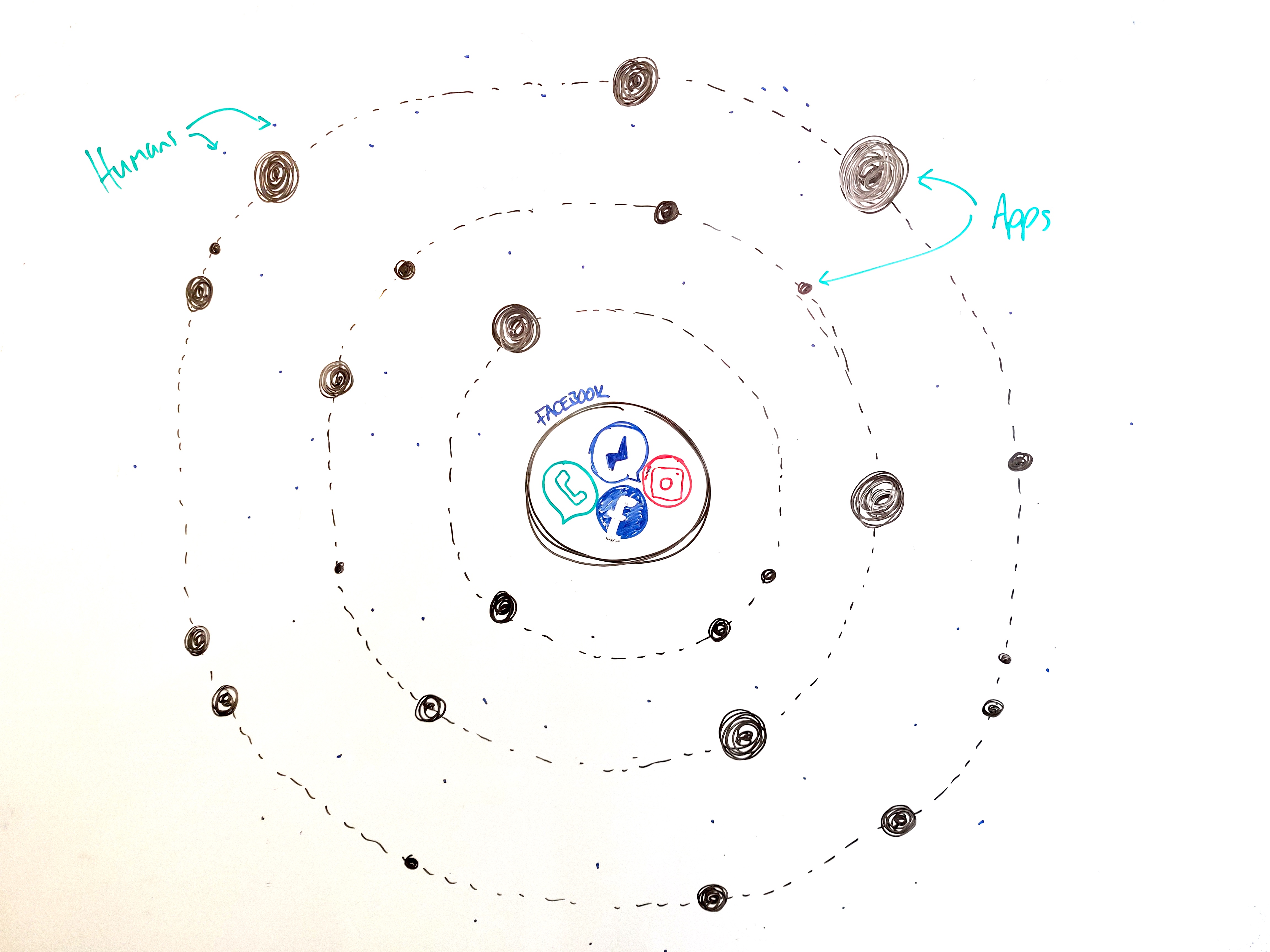

The digital solar system

The energy being released by Facebook is now immense and a rich ecosystem is feeding off of it.

- People are communicating through it

- Developers are building on it

- Third party apps are connecting to it

- Marketers are advertising on it

- Brands are digitally representing themselves on it

- Well-known celebrities are maintaining their status on it

- New celebrities are being created on it

- and so much more

Facebook has gone from a small clump of data to something at the centre of an entire digital solar system. We, human beings, are just mere particles of matter revolving around it.

Digital black holes

As Robert Scoble said in 2007: “I added the WordPress Facebook Application a few days ago. Now my blog, and your comments, are showing up on my Facebook Profile Page. Along with my Twitters. My Flickr photos. My Google Reader items. My Kyte videos. And a bunch of other things.”

Facebook is now sucking in data at uncontrollable rates, sometimes without us even knowing it. But where exactly is all of this data going? What’s being done with it? Can we get it back?

Black holes in our physical universe have an event horizon, beyond which nothing can return — not even light. Facebook seems to have its own event horizon, and beyond is a situation in which we have no idea what’s happening to our data. It’s chaos, it’s a digital black hole.

A lot of people refer to “the Facebook ecosystem”. I don’t think that does the true size justice. A better term might be “the Facebook Galaxy.”