Its general election season in Spain, and political parties want your data. As a citizen, The Friday List is a tool to re-vindicate your rights over your personal data — to tell lawmakers that they are not to be sold short.

Back in December of 2018, Spanish lawyers, academics and journalists all sounded the alarm. The addition of Article 58 bis to the Organic Law of the General Electorate Regime (LOREG) was bad news. The LOREG is the collection of laws that regulate the functioning of general, municipal and autonomic elections in Spain. Article 58 bis was introduced as part of the third wave of Data Protection Implementation Law - implementing the GDPR into national law.

So what is Article 58 bis? Article 58 bis regulates the use of technological means and personal data in electoral activities.

What does Article 58 bis do?

Article 58 bis allows for the collection and use of personal data relating to the political opinions of individuals by political parties in their electoral activities. Simply put, it allows for political parties to send out electoral propaganda by electronic means or messaging systems as long as certain conditions are followed.

The following conditions apply: (i) Data must be obtained from websites or other publicly accessible resources (ii) Proper safeguards must be provided (iii) The messages sent out by political parties must identify their electoral nature and (iv) The receiver of such messages must be provided with a simple and free means of opting out.

If all conditions are met, this use and collection of data by political parties is to be considered in the public interest. The public interest designation makes this collection and use lawful under Spanish law.

Why is this bad news?

Article 58 bis, as it stands, can give legal basis for the collection and processing of data by political parties in order to mass-send political spam. Moreover, it opens up a pandora’s’ box to facilitate the creation of “ideological profiles” by political parties during election season.

If it is so bad, how are lawmakers justifying it?

Those who stand behind the legislation wield GDPR Recital 56 as a democratic guarantee, as Article 58 bis is allegedly based on the GDPR Recital 56. The GDPR Recitals are important, as they provide additional information on the meaning of the articles, which in turn helps nation states adequately implement it into national law.

Recital 56 establishes that personal data relating to people’s political opinions may be processed if the following conditions expressed are met:

- The operation of the democratic system in a Member State requires that political parties compile such personal data and

- Appropriate safeguards are established.

Recital 56 has been ineffective in shooing away the concerns of those who detect Cambridge Analyticas’ ghost in the machine of Article 58 bis. The fact that Article 58 bis unanimously passed through Congress, without a single political party opposing it (what a coincidence!) hasn’t helped.

The language of Recital 56 is imprecise and allows Member States to define both elements of the justification: Who decides whether the democratic system of a country requires political parties to compile such personal data? Who defines what type of safeguards are appropriate, and oversees their implementation before any data is collected? Who will ensure that political parties delete all data collected once election season is over? The ocean of unethical implications is vast, particularly when the personalisation of electoral messaging is currently being sold as the end all be all of voter reach - on par with its widespread success in marketing contexts.

Enter the Friday List

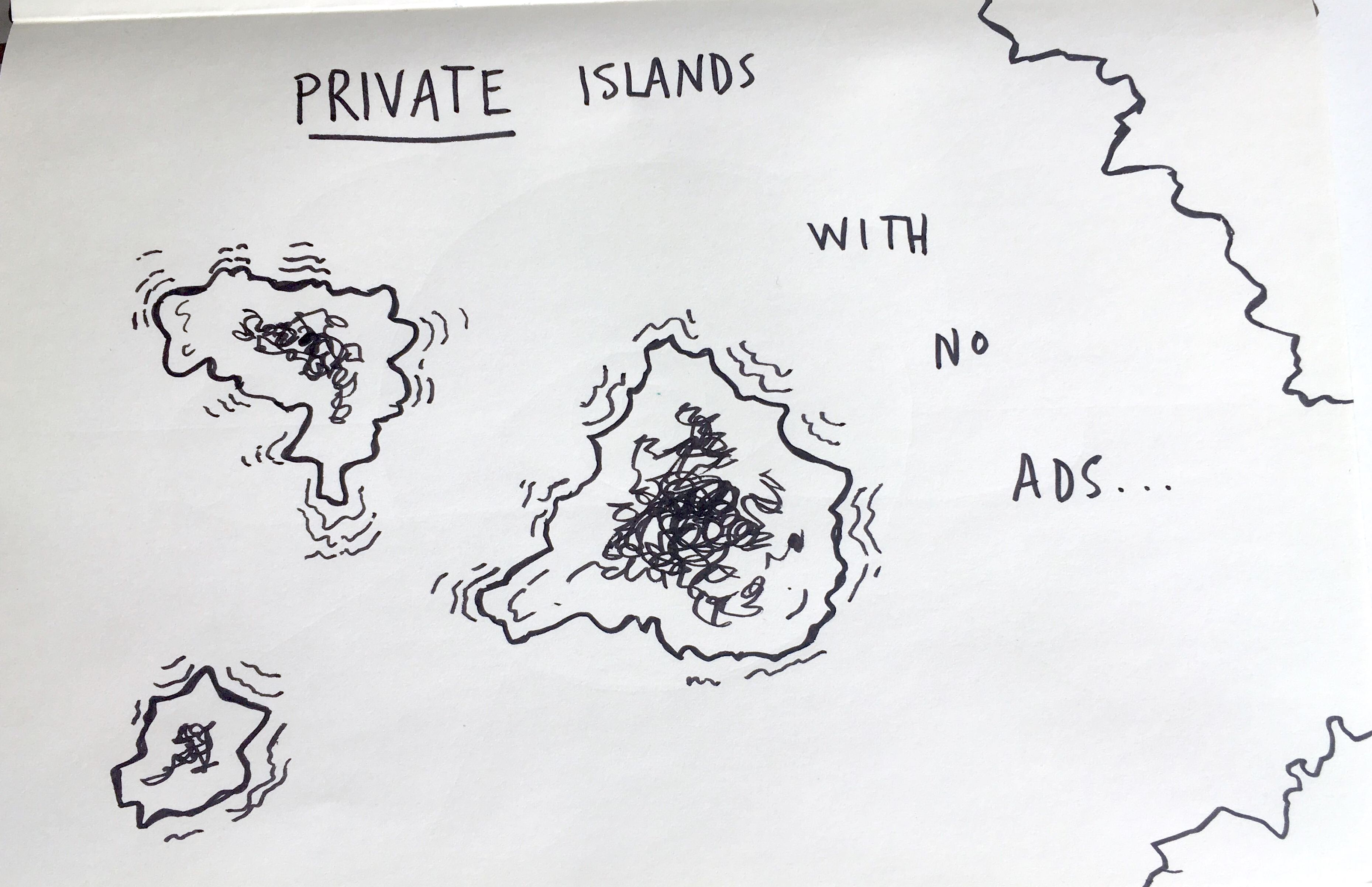

The Friday List is inspired by the “Robinson List”, executed by the Spanish Agency for the Digital Economy back in the 90s, in which citizens could voluntarily register in order to block publicity and advertisements from being sent to the registered email. The concept that inspired the name of the list, a reference to castaway Robinson Crusoe washing ashore on an island “where advertisements can’t reach”, is carried over by the Friday List.

The lack of an official watchdog has kick-started a civil society movement seeking to hold political parties to account, including an official recourse being filed with El Defensor del Pueblo (the Parliaments’ High Commissioner, operating independently from the institution). The Friday List, carried out by a group of privacy and data protection experts under the name of Secuoya Group, complements these institutional checks and balances by giving power back to the electorate.

So how does it work?

- The Friday List is open to any citizen who wishes to sign up and register their wish to not have mass electoral spam sent to their registered email, phone number or any other messaging service including Whatsapp — the largest messenger service in Spain.

- The Friday List is managed through the Foundation for the Defense of Privacy and Digital Rights, created by a subset of the Secuoya Group members. Its working capital, used to keep the website running and ensuring the safe processing of data, is 100% raised through a Goteo.org crowdfunding page.

- Its privacy guarantee is a double-blind encryption system. This allows political parties to know which contacts are off-limits without ever having access to Friday List data they previously didn’t have. Simply put, it is a matching game. If Citizen A is on the Friday List and is also on the list of people Party B was planning to spam, Party B can now cross Citizen A off their own list. Conversely, the lists’ management team never has access to the political party database.

Despite its clarity of purpose, transparency and privacy-by-design architecture, the list has no binding effect. The founders themselves admit that political parties are legally allowed to completely ignore it. However, the hope is that with a high amount of registration political parties will be forced to recognise it and scrub their own databases accordingly.

So far, March saw instances of up to three different political parties reaching out to a teenager over Whatsapp before electoral season had even started - outside of the permissible time frame. His mother, a Lawyer who specialises in Privacy and Data Protection Law, was quick to sound the alarm. Since then, multiple party-centric Whatsapp groups have been shut down - albeit as a result of infringing Whatsapps’ own terms and conditions, not as a result of public institutions reeling in the broad scope of Article 58 bis.

With the election over I reached out to interview Jorge Garcia Herrero, one of the founding members of Secuoya and architect of the Friday List, for a follow up and a personal reflection on the project.

“No political party has contacted us.” He tells me. The high number of registered users (around 6,000) has served to raise awareness among citizens, putting privacy on the frontline of a highly polarised election, but has not been enough to pressure political parties into voluntarily scrubbing their databases. However, Secuoya group is not giving up the fight.

After presenting a complaint to the Constitutional Court of Spain the same day that the Friday List was launched, Secuoya Group recently presented a similarly-worded complaint to the European Commission. Jorge hopes its outcome will prove more than just a slap on the wrist. The complaint, written in no-nonsense language, denounces the waiving of GDPR Article 9.2.g (Substantial Public Interest) and Recital 56 as justifications for this type of data processing. It equates it to the legislative body “washing their hands clean” of responsibility — leaving citizens’ rights to data protection in political parties’ hands.

Whether the parties will choose act in good faith regardless, letting go of all the data collected during election season now that it is over, remains to be seen. As of today, there is still no official watchdog. The Spanish Agency For Data Protection issued a list of suggestive safeguards that political parties ought to follow, but this is insufficient, Jorge says. As stated in the complaint, such safeguards should have the power of law in order to protect the rights of data subjects and enact any sort of binding effect on political parties.

It’s important to not be discouraged, however, as that is when most rights are lost. Frequently, in the realm of privacy, rights have a tendency to be freely given in exchange for some sense of convenience. The Friday List is a commendable example of swimming against the current, encouraging citizens to take an active role — demanding that national institutions ensure an adequate protection of the rights conferred to us through the GDPR and denouncing each legislative instance that aims at chipping away those rights.

The Friday List is an independent effort undertaken by scholars and lawyers, so other EU countries could implement their own versions if they so desired. It is likely that with such a push, legislative bodies would take note that citizens are not passive in defending their rights. In a sea of data-driven politics, islands of privacy can only exist if we organise to keep wandering sharks at bay.

Marina is working towards a LL.M certification at Ohio State University Moritz College of Law. Marina likes to look at the human side of technology, surveillance, privacy, and the governance of those things.