Student data in the US is being harvested for commercial profit — it’s amazing what you can do without transparency.

Getting spam is not news. Practically every online activity, from shopping to liking a page on Facebook, leaves a substantial papertrail that data brokers (companies that buy and sell information about internet users from various sources) can easily tap into. Getting spam on your college email account, however, is a little more suspicious. Sure, “no harm” will come from me knowing the cafe across campus has a lunch special. But when I was confronted with the following, I have to admit I was a bit more surprised.

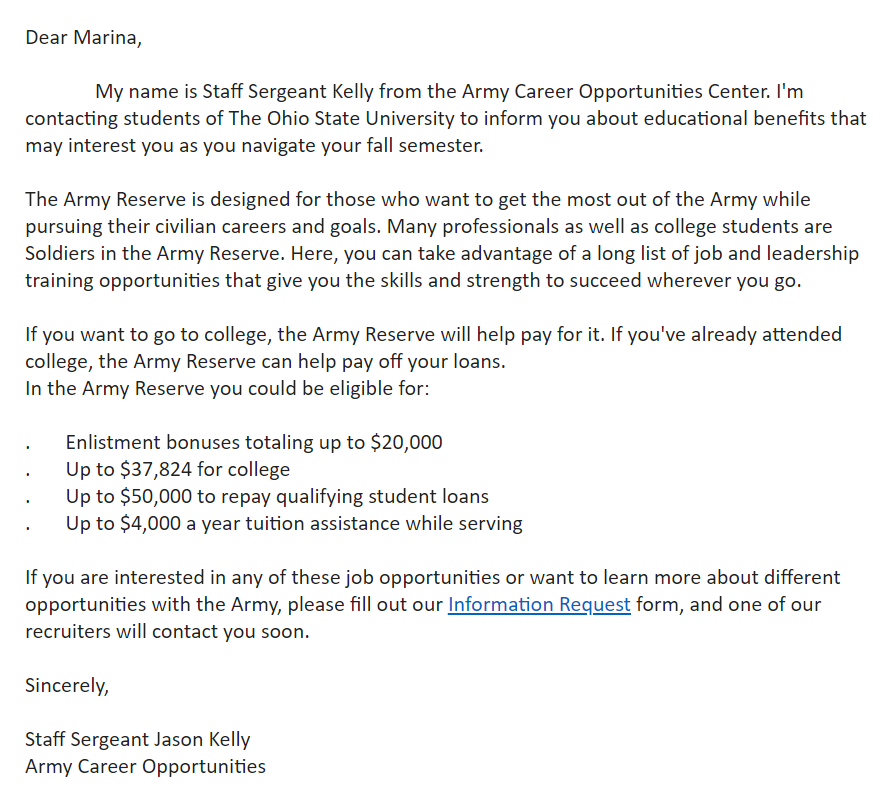

Military recruiters walking around in uniform on a U.S campus is a sight I’m still adjusting to. Who knew I would have to continue to adjust to it, after just finishing my last final. Would online military recruiters follow me, through my college email account, even after graduation?

Surely this was just a mistake. Big data analytics allows for all the scattered information collected through your online footprints to be cross referenced, forming a “user profile”. However, the assumptions algorithms make about the person behind the data are not always accurate. In the case of crime-predicting algorithms, for example, they perform marginally worse than untrained humans at predicting recidivism in criminals.

In the case of crime-predicting algorithms they perform marginally worse than untrained humans at predicting recidivism in criminals.

The email I received is another example. For starters, I am not a U.S Citizen or permanent resident. How could I be getting targeted for Army Reserve jobs, when one of the key requirements is just that? Moreover, how did the “Army Career Opportunities Center” get ahold of my student email? Besides it being my official login to campus computers on a private network, I had not used it on any other platform. I probed around — maybe I had been more reckless than I remembered.

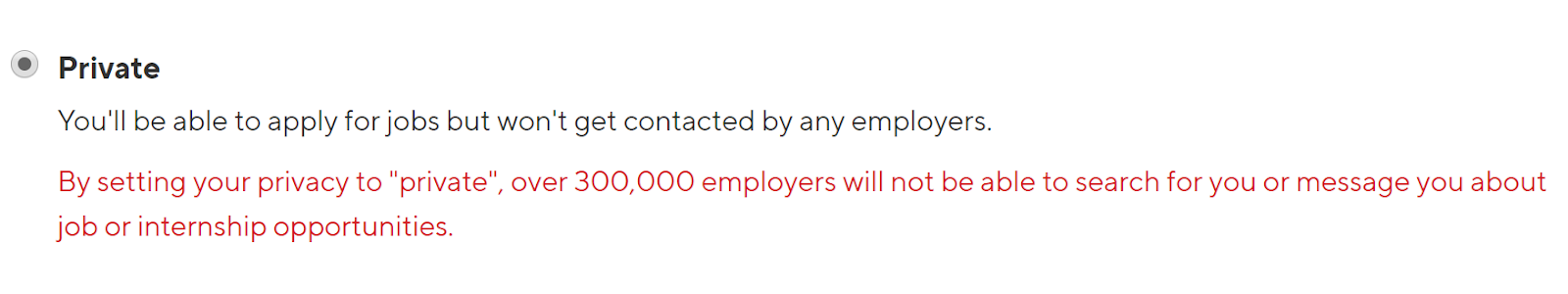

The jobsite platform with which my university had partnered was the only place I had ever used my student email as a login. Despite its passive-aggressive language, I had set up the most restrictive privacy settings.

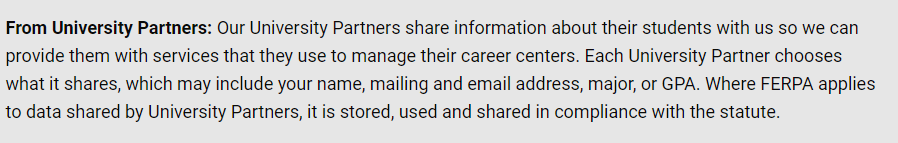

So, what does the job platforms’ privacy policy look like?

This got me thinking — was the patchwork of privacy legislation scattered across all 51 states allowing this to fall through the cracks? Was a legal loophole responsible for my name and student email being up for grabs? Was the marketplace for student data regulated at all in the U.S? Turns out, yes and no.

The legal framework

Currently, there is no federal privacy law in the United States that specifically targets the use, retention or resale of student data by private-sector data brokers. The information bought and sold by data brokers can be used for many purposes, such as analysing trends, or selling lists of contact information for various categories of consumers for commercial advertising or direct marketing. This is what leads to your student inbox getting cluttered with solicitations, from lunch special coupons to (you guessed it!) military recruitment.

So what potentially applicable laws are there?

- The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA) is a federal law that prohibits schools and teachers from sharing information from a student’s educational record (this includes contact information, demographics or performance/grades). However, FERPA does not directly apply to private-sector data brokers and some student data types fall outside of FERPA’s scope. This out of scope information is highly valuable to data brokers because it often includes metadata obtained from the student interacting with an app or a third party service.

- FERPA provides strong protection because it prohibits the disclosure of educational records unless a student provides express written consent to such disclosure. However, there are exceptions that allow various types of data disclosure to fall through the cracks - as schools and teachers do not require a student’s consent to disclose them. One of them is the Directory Information Exception. Data designated by the school or district as directory information is considered public and may be disclosed without consent. Examples of directory information about students include name, address, telephone number, email address, date and place of birth, grade level, sports participation, and honors or awards received. Pretty broad!

- The 121 state student privacy laws passed since 2013 place strict requirements around student information held by local and state education agencies (known as LEAs or SEAs), or data that third parties obtain in order to fulfil a school function for an LEA or SEA. However, data brokers remain largely unaccounted for. Ohio, as I found out, regulates LEAs or SEAs directly but does not regulate third parties or vendors.

Why is that a problem? A cluttered inbox never hurt nobody…

That’s true, but that does not make me feel any better. The problem with the marketplace of student data is its fundamental lack of transparency. Data that was allowed to be collected under the law for a certain purpose (educational) ends up being used for another purpose all together (commercial) — and no one can tell where things went wrong.

A recent study by the Center on Law and Information Policy (CLIP) at Fordham University points out that it is nearly impossible to find just where the data is coming from. Data broker companies have a habit of changing names and merging amongst themselves, which further complicates the task of figuring out who they are and whose data they manage. The school districts in question deny selling directory information other than to regulated LEAs or SEAs — but the emails just keep coming. From the 232 commercial solicitations that the students in the study received, over 90% were categorised as related to education, including financial aid products and military recruitment. Under the current law, these are still considered “acceptable” uses.

The problem with the marketplace of student data is its fundamental lack of transparency.

However, emails from Scholarship.com, for example, where students can input a huge amount of data (from allergies to immigration status) to check their eligibility for available awards, is managed by a company called American Student Marketing. This data broker, among many others identified in the study, packages student data into different categories and sells it for purposes wholly unrelated to education. It is no leap of the imagination, then, to connect the over 20 non-educational emails received by the students in the study (from insurance companies offering premium rates to a company marketing trips to Niagara Falls) as the end result of that data journey.

The “opt-out” labyrinth and the promise of the “free service”

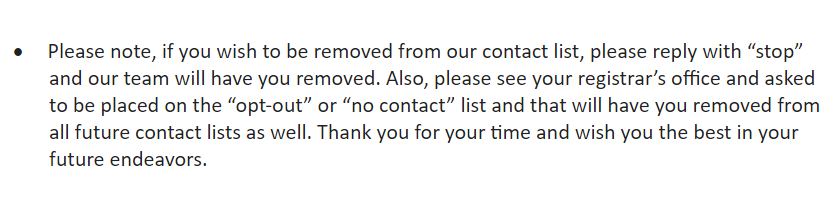

A lot of data brokers defend their collection and use of student data by pointing to the opt-out options in their privacy policy. That was certainly the case for the Army Careers Opportunity Center that reached out to me, as seen below:

The problem with the opt-out process, in some cases, is that it is ineffectively circular. As stated previously, data brokers have affiliate relationships — frequently merging, buying and selling data from one another. There is nothing in the law preventing data brokers from requesting that you opt out of their particular data collection each time your data changes hands. The case of military recruitment provides a clear example. You can opt-out at the registrar’s office at your school, but you cannot opt out of JAMRS.

The Joint Advertising Marketing Research Studies list is a massive registry of 30 million Americans between the ages of 16 and 25 administered by the Department of Defence for military recruitment purposes. Much of the information obtained is through engagement with data brokers — particularly companies that specialise in collecting information about youth. After settling a suit challenging the constitutionality of the database, the Department of Defence is now forced to keep the information only for up to three years. However, there is no technical way to get your name out of the database. According to the DOD’s opt out procedures, if you ask nicely in the opt-out form they will keep your name in a “suppression file” — supposedly out of hands of the recruiters. There is no mention of the suppression file being kept away from the grabby hands of brokers, through, and so the cycle continues.

Companies offering educational services, such as scholarship.com, also frame their relationships with data brokers as ‘necessary’ to keep their services free. Kevin Ladd, the vice president of Scholarship.com, is quoted as saying “It’s like anything else. You can either pay for something and not have the ads, or you can get it for free and have the ads. That’s life in the digital age.” But surely, the same cannot be said when you are bartering with sensitive data tied to a student’s ability to continue to study, right? More so if that initial data, provided by the student with a clear aim to improve their situation, is then used against them to market products they do not want or need? Despite the CLIP study stating that it is an undeniable public policy concern, the law remains silent.

What does this mean, then? Will I continue to know about the lunch special across campus and about gracious military service funding way after graduation, even after I cross the pond? Most likely.

Marina is has a LL.M certification at Ohio State University Moritz College of Law. Marina likes to look at the human side of technology, surveillance, privacy, and the governance of those things.