The world of online advertising is confusing and abstract, so let’s just clear some things up…

It is a model whereby our behaviour, attention, and experiences are made available for profit. For the everyday user of the internet, this is extremely intrusive and annoying.

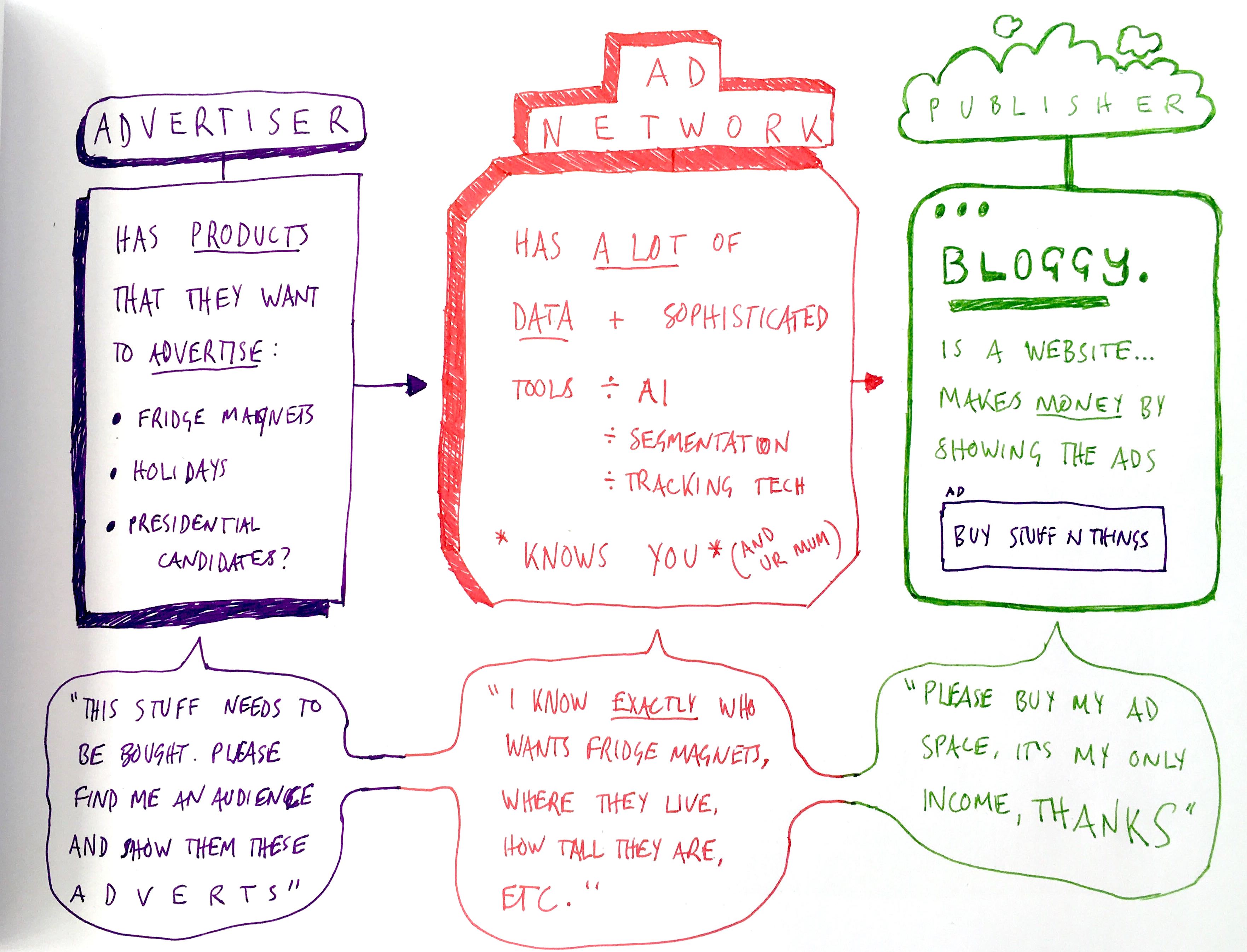

A birds-eye view of the online advertising business

A birds-eye view of the online advertising business

To break it down simply:

🤹♂️ Advertisers want to show their ads — but only to the correct people to increase the likelihood of conversions.

📊 Advertisers call on ad networks, e.g. Facebook or Google. Because these guys are the ones with all the data and resources — they know who likes what.

🧩 Ad networks will distribute ads to the correct publishers (blogs, news websites, etc) so that they reach the best audiences. Which is why websites like The Guardian set so many cookies. Those are the ad networks, working their magic.

Some issues with this model: besides the fact that it doesn’t respect people’s data, it also just is not that effective. Publishers only receive about 4% more revenue from behavioural advertising than they do from the non-targeted kind. Furthermore, one of the main reasons why people use ad blockers is because they find online ads irrelevant and annoying, completely dispelling the idea of ‘personalised’ ads.

😮 And now for another interesting fact: it’s very possible you are reading this from within the bubble of tech-savvy internet users who enjoy utilising ad-blocking technology on their browsers, but: less than half of us are actually blocking ads, globally. In the UK, only 22% of internet users were blocking ads in 2018.

But that’s just ads, what about cookies and other tracking technologies? Even fewer people use more nuanced tools such as Privacy Badger which learns to block trackers as your browse. Tools like this try to make things like real-time bidding (RTB) much harder for advertisers.

RTB happens all the over the web to serve users ads; it’s about time we had a look at how it works so that all of this ad talk gets a little less abstract.

Real-time bidding is fast and automatic, and it doesn’t care if you use an ad-blocker.

Forget about the internet for a minute (just ONE minute). Let’s take this into the real world so we can actually see what’s happening. Here’s how RTB would feel if websites were physical shops:

You’re walking down your local high street, and you go into a bunch of different shops. You browse around the T-shirt shop, but you don’t buy anything. Shop assistants stare at you and take notes. As you leave, they put a sticker on your back with the shop logo on it.

You go to the trinket shop, pick up a candle stick, regard it with cold indifference, and put it down again. As before, there are shop assistants taking notes. When you leave you get another sticker on your back.

This happens at every shop you visit. You don’t buy anything at any point… you’re just browsing around and passing the time. You now have several stickers on your back, and an extensive profile of information about you compiled by all those nosey shop assistants.

Now it’s time to do some serious shopping. You go to a giant shopping centre where everything is cheaper (how dare you — please support your local economy). From the moment you walk in, all the information about you that was gathered on your local high street is now broadcast to every single outlet in this shopping centre.

✨ Choose your own adventure: do you block ads or not? Here are two different scenarios:

Without an ad-blocker droves of people start vying for your attention: “I see that you’ve previously expressed an interested in candle sticks. Come to our candle shop for the best candle deals” and “It looks like you’re in your late 20s and have visited an outdoor sports shop recently… would you like to buy some camping gear?”. Everyone is very annoying and they are actually making it harder for you to find what you need.

With an ad-blocker, the same droves of people swarm around you trying to get you to buy things — but now you have a special pair of sunglasses that blocks them from sight, and some noise-cancelling headphones.

Methods as aggressive as RTB still happen in the background, whether you block ads or not. What happened in the shopping centre was a result of data that had already been gathered about you. Therefore, the trick is to stop the tracking in the first place.

There’s hope, because trends are changing

By 2018, 64% of tracking cookies were blocked by browsers. This is promising, considering the lengths ad networks such as Google will go to in order to keep RTB alive.

In 2019, Firefox started blocking tracking cookies by default. There appears to be a rising trend of this — even Chrome are dabbling in tracker blocking. If browsers can successfully duplicate the functionality of blockers as sophisticated as uBlock Origin and Privacy Badger, the responsibility to maintain privacy goes out of the user’s hands, and to the browser.