Don’t be scared of this regulation, it could actually end your cookie headaches.

The new cookie consent rules that the ePrivacy Regulation will give the internet will plug some holes that the GDPR does not account for. Here are the broad strokes of these new cookie rules:

👐 The responsibility of cookie consent management could be spread out a bit more: handling this messy problem does not need to be limited to cookie banners — this regulation says that it could be done at a browser or operating system level.

🧱 Notices that essentially block access to an entire website are allowed, as long as users can view a version of the site that does not set or send cookies/other third party requests

👩⚖️ The standard for what qualifies as ‘consent’ for accepting cookies is pretty much the same as GDPR, but with more exemptions, which makes it a bit more… realistic, in practice.

Let’s look at these three things in more detail…

1. You don’t need a cookie banner

Something that stands out about the cookie rules in the ePrivacy Regulation is that they have — indirectly — highlighted how tired users are of cookie banners. They have used the phrase (in previous drafts) ‘consent fatigue’ which refers to users being overloaded with requests to accept cookies. The latest version says that all these requests “can lead to a situation where consent request information is no longer read and the protection offered by consent is undermined”

In other words, people just ignore cookie banners now, and that makes them a bit useless. The regulation goes on to heavily recommend the following:

- That ‘providers of software’ should be the ones who provide clear, user-friendly controls for cookies

- In this case, ‘providers of software’ means not the websites, but the browser or even operating system

- Users should be able to ‘whitelist’ whatever providers they want, meaning they accept certain (or even all) cookies set by those providers

This is a game-changer: it means users could literally decide that they are fine with whatever cookies yourcompany.com will set in their browser (because they trust that company), and can make that known at a browser level — no need for yourcompany.com to set up a cookie banner 😱.

2. Putting walls in front of content is fine — if you offer an alternative

Surprisingly, walls that block content, forcing users to make a choice, are allowed. But note:

- You can’t just say ‘either accept cookies or you can’t come in’ like some backward tea party

- You must offer a viable alternative if someone doesn’t want cookies or tracking technologies — e.g. a version of your website that does not set such cookies.

- If your site is there so that people can access a public service, you cannot use any kind of wall; you may be offering a service that some people have to access, because they rely on it. Blocking them from using the service until they accept cookies is not allowed.

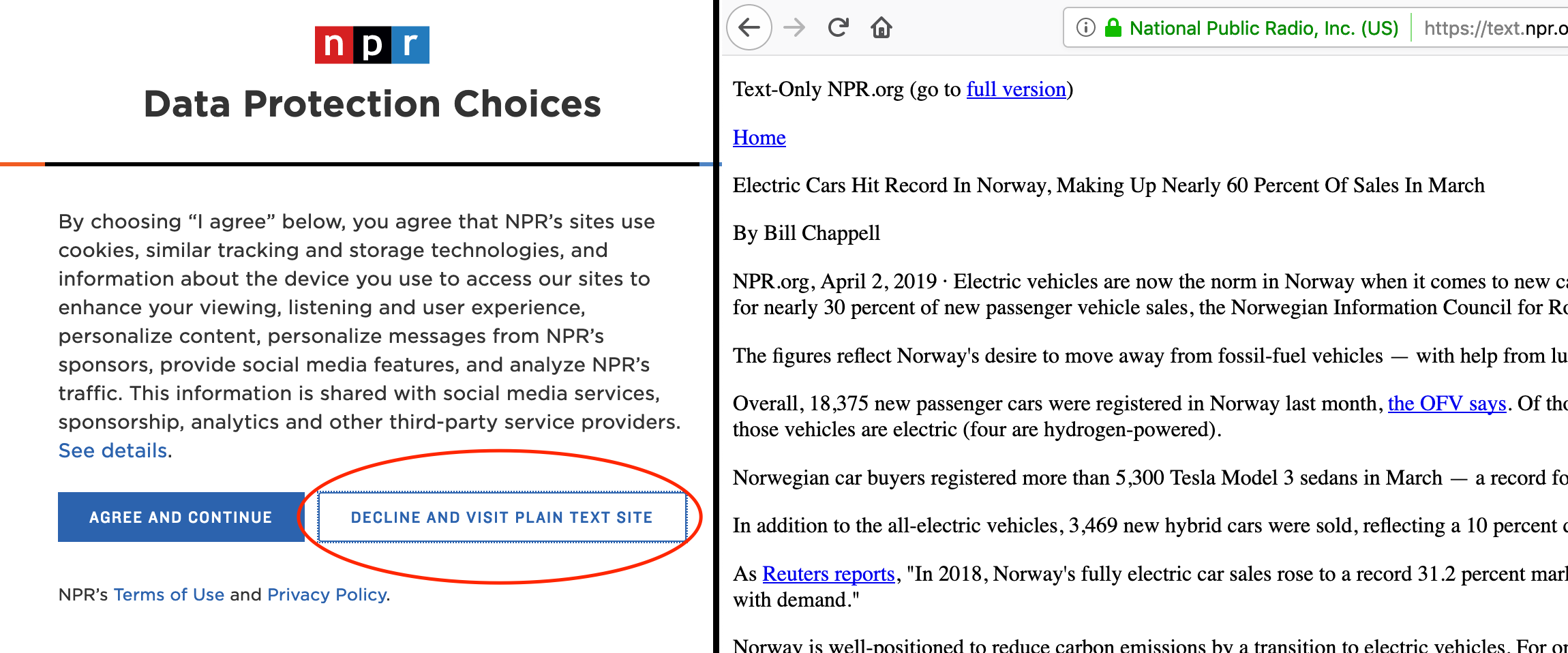

No frills, but no tracking: the left shows the message from NPR before you are allowed to read the article, and the right shows the plain text article

No frills, but no tracking: the left shows the message from NPR before you are allowed to read the article, and the right shows the plain text article

There are sites that are already doing versions of this; news site NPR have taken a no frills, no tracking approach: the above screenshot shows a wall which gives users a choice between being tracked while visiting the normal site, or rejecting all of that but only being shown a plain text site. Not sure if this is NPR’s best idea, but plain text is less distracting I guess? 🤔

3. The exemptions when it comes to consent

The ePrivacy Regulation says that when it comes to cookie consent, the GDPR standard must be followed. So that means, you need consent to set or send any cookies that are not absolutely essential to deliver your services to your users. According to the latest draft of the ePR:

“This may include the storing of cookies for the duration of a single established session on a website to keep track of the end-user’s input when filling in online forms over several pages, authentication session cookies used to verify the identity of end-users engaged in online transactions or cookies used to remember items selected by the end-user and placed in shopping basket.” Recital 21, ePrivacy Regulation draft 4

☝️Note: within the scope of these rules is also the general storing and retrieving of information to and from people’s devices — so that includes any scripts or tags that may send requests, etc.

But, here’s the burning question: when are you allowed to send/store information without consent?

⌚️ When the user is interacting with the Internet of Things: if a watch or smart thermostat needs to send or store information in order to perform a function that the user specifically requested, it should be left to its own devices (pun very much intended)

📊 When gathering anonymous site/web app statistics: e.g. ‘how many visitors did this page get?’ or ‘how many of my users access this dashboard every week?’

🕵️♀️ When fixing vulnerabilities and bugs: if you need to store things on users’ devices, like when patching or updating. As long as doing this does not effect that user’s current privacy settings, and the user can postpone or turn off automatic updates.

To conclude: these cookie rules are a lot more rigorous — and aligned with real-world usage of websites — than what we have now, so much like GDPR did, they could change the way the web as a whole ‘handles’ data privacy.