Greetings reader, here is a short piece of data ethics fiction for you to absorb:

Julia is in prison and every morning has ‘cell inspection’ with her cell mate Aubrey. Aubrey has a smell that reminds Julia of old dead leaves but Julia is now used to this because she’s in prison and there are much worse things about prison than this smell. During cell inspection they have to stand outside their cells, perfectly dressed in their convict uniforms, while a prison guard inspects their cell.

“This is… what is this?” the prison guard points to the ground with their ‘guard stick’ which is used for beatings and other guard-related activities. There is a chess set sitting there.

“That’s our chess set,” says Julia, “we use it to play chess. It helps pass the time. Prison is really boring”

“We carved it out of soap,” says Aubrey.

“Yeah but you can’t actually do that because it’s against prison rules. Soap is for cleaning yourself - not for playing chess. And carving is an activity enjoyed by non-convicts only.”

The chess is taken away, as are the carving materials. Julia and Aubrey go back to being bored. The prison guard continues ‘cell inspection’. It takes roughly three hours of their time. It’s really hard to properly inspect each cell individually for rule-breaking.

The prison guard goes to the president of the prison with a suggestion to make this process more efficient, “every guard has to spend ages checking on every cell - can we not just look at all the cells at once? Then we’ll have more time for beer pong and polishing our guard sticks”

“Cool idea” says the president.

So then they turn the prison into a giant circle. There is a special ‘guard seat’ right in the middle, and all the cells are around the outside. A guard sitting in the ‘guard seat’ can see into every cell very easily, which means no one ever breaks the rules because they know they are always being watched.

But the really funny thing that the convicts do not realise is that there is hardly ever a guard in the ‘guard seat’. They do not realise this because they cannot see the guard seat. They spend all their time not breaking the rules and behaving like ideal convicts, even though someone is only watching them some of the time.

“This is genius” says the president, “you will be promoted from Lesser Guard to Greater Guard”

The guard is happy. The convicts never break the rules again.

Fiction over. Back to reality with you, reader. The new prison design I described in this nonsense story is called a Panopticon, and it’s real. What does this have to do with anything? Very much — please read on.

![]()

The Panopticon model makes it so that the prisoners live with the idea that someone might be watching them at any given moment. ‘Might’ being the operative word here; inside a panopticon you can inspire a widespread change in everyday behaviour from the mere suggestion that there could be someone watching.

Hmm… what does that remind you of then? Ha, yes of course: real life. In the west, almost without anyone noticing, private companies have successfully harnessed the power of the internet and have cultivated an ecosystem in which we are always being watched. Whether it’s a thousand ad networks or someone you just matched with on Tinder, there is always a possibility that you are being looked at.

Eep, scary 😮

* Takes a selfie with a matcha tea latte *

When you post something on social media, there is a possibility that everyone will scroll straight past it without saying anything or paying attention, and it will be like it never happened. But, it did happen, and every time you post something online there is potential for some people — or a lot of people — to notice it. Therefore, all of us, in some way, make sure that what we share is ‘good’.

Now, ‘good’ can mean so many things: cool party, cool holiday, cool outfit, cool new relationship. It can also mean a shared distain for public transport or a really interesting take on politics or new TV show; either way, whatever person you present on social media is most certainly behaving like someone is watching.

This stuff is not new. We’ve been doing social media for ages. In 2019, it’s almost like there are two camps of people. The first camp is the one that lets their food go cold while they take a photo and add it to their instagram story. The second camp is entirely made up of people who just laugh at the first camp.

Dating apps are another thing — I’ve never seen the human race change it’s behaviour as hard as it has when using dating apps. You pick a heavily curated selection of photographs that make you look ‘fun’, or your approximation of that. You try your best to sound charming, witty, and interesting with every single message you send. You give up and get a ghostwriter to do it all for you (that’s a real thing, click here for lols or to get a job as a dating app ghostwriter).

What’s more, if you know someone’s watching you will put measures in place to protect yourself: we download ad blockers, we go incognito, we use password managers. But these things are to do with security and privacy — whether effective or not, these changes in behaviour somehow make us feel safer and more private.

‘Being private’ isn’t really a thing right now - but it also doesn’t matter

What does it even mean to be ‘more private’? Are people scared of being attacked somehow? In actuality, as you browse the vast depths of the internet, the punishing number of tracking technologies being tacked onto you are there to serve you more personalised ads — not to spy on you in order to attack you.

So yes, on the whole, a ‘lack of privacy’ (e.g. being watched all the time like in a panopticon), really just means ‘being open to floods of targeted advertising’. It’s quite hard to fully stop this from happening, and does it really matter anyway? An ad is just an ad, do you even care if it’s personalised?

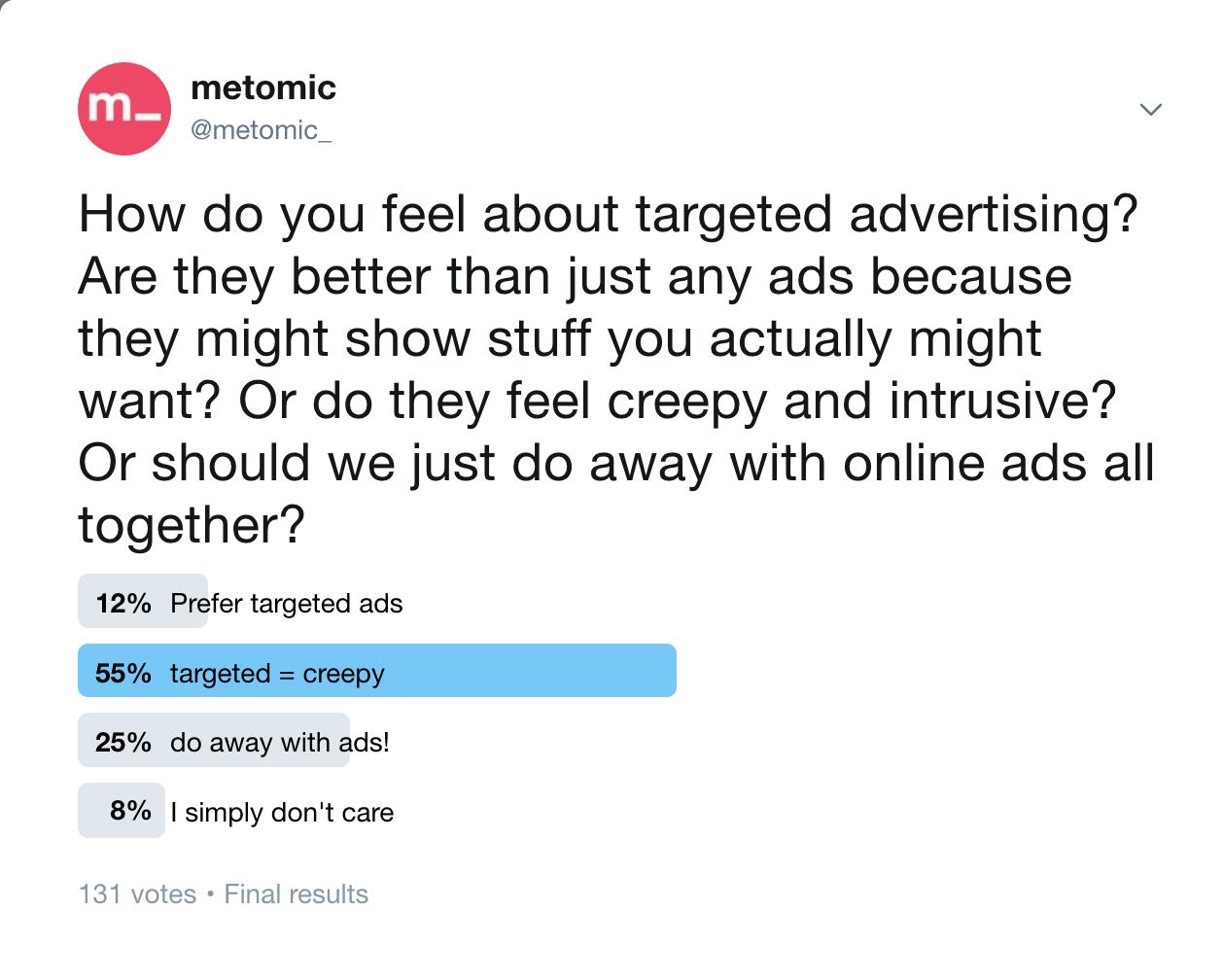

We actually did a Twitter poll about this recently and it turned out that those who voted just found targeted ads plain creepy. So does this mean the intrusiveness of a targeted ad out-weighs the benefit of being advertised a product that you might actually want to buy?

Perhaps it’s the very idea that an abstract, virtual, cluster of networks somehow knows that one of your closest friends has a birthday coming up and really likes Batman doesn’t sit well. Also, your behavioural and personal data being processed and compared with other similar data manifesting as a shockingly accurate targeted ad can make you feel like you’ve been tricked, in a way.

So what I’m saying here is that the need to ‘be private’ is purely an emotional reaction to something that we cannot control. I’m already resigned to the fact that there are faceless, powerful, entities that know a lot about me and what I might do next. I do not feel intruded on anymore — I’m just mad that they are constantly profiting off of it and, thanks to a blinding level of opaqueness, there’s no clear way to stop it.

This nonsense was perfectly illustrated in Mad Men when Betty Draper unwittingly fell into a marketing trap set up by her own husband. Don Draper, advertising extraordinaire, decided that the US citizens who were most likely going to buy Heineken (fancy imported beer), were housewives from rich families. So his wife was the market and he targeted her with ads. She threw a dinner party and bought the beer and had no idea what was going on, which in turn made her feel silly and embarrassed.

Betty Draper planning a dinner party

Betty Draper planning a dinner party

This marketing experiment would not have worked if Don told Betty about it beforehand — she’s not going to buy Heineken just because someone flat out asks her to buy Heineken. She’s going to buy Heineken because she (thinks) that she wants to buy it. She had no idea that she had been identified as a viable market for Heineken, so had no chance to change her behaviour in any way.

Betty’s reaction is so inline with how you or I could respond to a targeted ad; buying Heineken for her was the result of a powerful machine that she cannot fully comprehend (Don’s advertising agency) knowing her better than she knows herself. She just thought she was buying cool beer for her party.

Well, we just think we’re browsing Facebook, booking flights, and buying birthday presents, I guess. And we are, but the person in the old ‘guard seat’ in the middle of our panopticon is taking very thorough notes.

What if you just didn’t know or care about being watched?

Now, if at Betty’s dinner party, Don and his colleagues decided to not laugh at her and reveal the sneaky marketing ploy, she would have most likely trotted through life without a care in the world, enjoying Heineken without feeling so seen.

That’s all cool for her though because she’s a fictional character from a TV show set in the 60s. Us nowadays-consumers are living in contemporary society online, and we can see the crap that our panopticon model produces more and more everyday. This article neatly explains what demographics you are stuffed in for the purpose of advertising. Some people have seen ads so timely and specific that they genuinely believe Facebook are somehow listening in via their microphone. Others go on using free services, not fully aware of how much large corporations value the data they unwittingly produce.

Right, but, many of us just don’t care. My girlfriend loves playing Candy Crush because it’s fun and fills up idle time. She knows that out of every game you can play on your phone, it’s probably the one collecting and processing your data the most. She does not care about this — she gets to play an engaging game entirely for free.

She’s right (takes a lot for me to admit that about her, so she MUST be right). We should not have to put up with this nonsense for the sake of Instagramming your lunch or trying to organise a birthday party via Facebook. All these products and services are free, but the majority of users do not understand why they are free.

Data needs to be collected, but there must be a middle ground that doesn’t leave you feeling like a put-upon Betty Draper, organising a tragic dinner party in your panopticon cell.