What does this mean? On the surface the internet will be made available for communities who would otherwise go without

This is a good thing, right? Yes. End of article. Just kidding, don’t be silly. This new wave of connectivity provided to the world raises many questions: if big tech become the providers of the internet, what does that mean for their control and influence over the data we produce for them?

Facebook, Google, and Amazon are currently putting a lot of money and resources into projects to deliver internet to those they refer to as the ‘under-bandwidthed’ (that term is a Jeff Bezos original). The solutions coming out of this span from gargantuan subsea cables to constellations of low earth orbit satellites. It’s all very futury, and it could lead to causing a mess in what is already a messy internet.

If big tech become the providers of the internet, what does that mean for their control and influence over the data we produce for them?

Each tech giant has their own way of doing this; below I shall provide a snapshot of the various projects that are being undertaken so you can get a fairly simple overview of what is being planned, and the sheer scale of it.

Loon

Earlier this year Google got a hefty cash injection for project Loon; a network of stratospheric balloons pumped full of broadband. They work like this:

- It’s a cell tower, but in the air: wireless internet signal is beamed to the balloons from the ground from a network operator (a partner — not owned by Loon); the balloons carry that signal and pass it on to devices which would otherwise be out of reach

- They are solar powered: the sun keeps the balloons going during the day, and charges a battery for night time usage. They stay up for over 100 days before returning to the ground in a soft, cushiony landing

- They live above the clouds: and planes, and weather. In the stratosphere, basically. High up enough that planes don’t crash into them and low down enough that they don’t float out into space.

A Loon ballon. It’s actually the size of a tennis court :o

A Loon ballon. It’s actually the size of a tennis court :o

International subsea fibre-optic cables

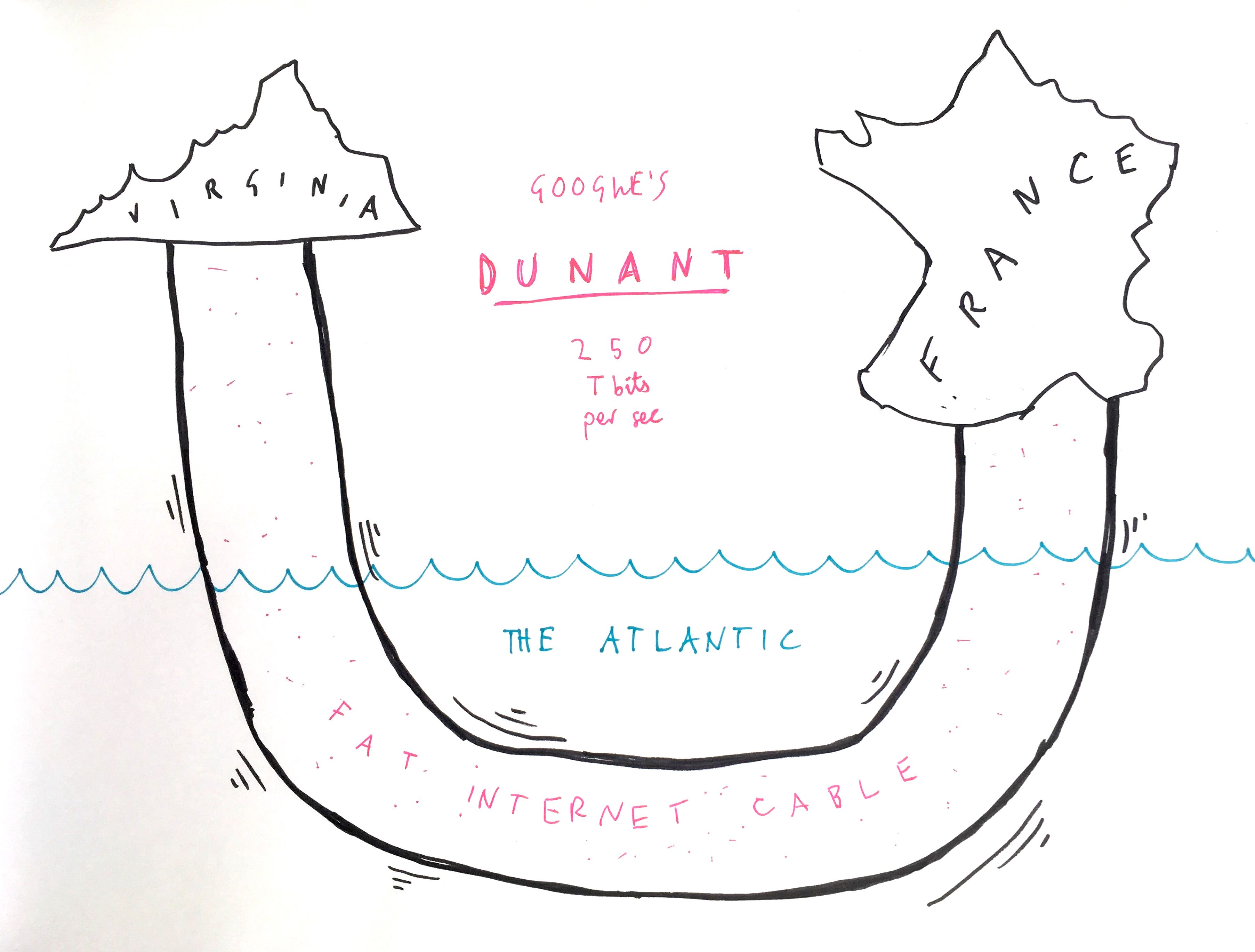

By 2021 Google will have three private cables running around the world. The point of these is both to transfer data quicker, and provide more connectivity in places that need it. Once having the tallest building or the longest bridge was how you asserted your dominance; we’ve added bandwidth to that pile of weird flexes now.

Dunant is coming in 2020 and will run from Virginia to France. It will be able to send 250 terabits per second. This is because Dunant is the fattest fibre-optic cable so far. The most fibre pairs we’d seen in a cable before this was eight. Dunant one has twelve. So… yep that’s pretty fast.

Curie was completed earlier this year and connects California and Chile. This won’t be as fast as Dunant but it’s the first new cable they’ve had in Chile in twenty years. It will be the main data pipe for that region.

Equiano will go from Portugal to South Africa and will be complete by 2021. This one will very much be serving the unconnected — there will be many branching units along the way, the first being in Nigeria.

Once having the tallest building or the longest bridge was how you asserted your dominance; we've added bandwidth to that pile of weird flexes now.

Now it’s important to bare in mind that all these cables are private: they are entirely owned by Google. So they have full control, and get all the bandwidth, allowing them to funnel data back and forth faster than ever before. For you, this means that video chat is about to become a lot less laggy and annoying. For them it means something else. Read on to find out.

Amazon

Amazon have nothing concrete yet, but have announced project Kuiper which will launch over 3,000 satellites into low Earth orbit. The details are not yet clear but the reasoning is the same as Loon: give internet to those who don’t have it yet. They want their satellites to span from the southern-most point of South America, to the top of Scotland. That should theoretically cover 95% of the population.

This is also more cost-effective way of doing it. Believe it or not, a constellation of satellites in the stratosphere is cheaper to execute than traditional ground-based satellites, and even has lower latency. For these to work, however, you of course need a network of stations on the ground for the orbiting satellites to talk to. Luckily, Amazon already have this and will not have to outsource, like Google is with Loon.

Simba

Facebook actually already have a transatlantic cable named Marea, but they’re sharing that with Microsoft. At the time, this cable broke all sorts of barriers but Google’s Dunant has made it look as impressive as hanging a cup and string from your bedroom window to your treehouse. They’ve recently announced project Simba, which will be an under sea cable circling the African continent.

What Facebook are also using (which is smart and cheap) is using what the industry calls dark fibre. These are cables that are just lying there, completely abandoned, taking up space. Facebook has been making use of these for a while, and now they are in use “pretty much everywhere” according to Najam Ahmad, Facebook’s vice president of network engineering.

Free Basics

This isn’t new but it’s part of what I’m talking about here, which is dominating internet provider space. Facebook Free Basics provides a gateway to a selection of websites and services, in ‘light’ mode — so you can read the news and (obviously) use Facebook without having to pay for data.

If a tech giant own the channels through which people receive an internet connection, then that tech giant has first hand access to what you do online.

Free basics leads me perfectly to the problem: if a tech giant own the channels through which people receive an internet connection, then that tech giant has first hand access to what you do online. If that’s the case, are things such as tracking pixels still necessary?

Sounds amazing, right?

Getting more people online is most certainly a good thing, but the players driving this change present some issues. Think about it: if Google or Facebook or Amazon ‘own the pipes’ through which you get your internet connection, are they not essentially a high-level ISP?

The cables and satellites I’ve talked about here are mostly privately owned. That means if they wanted to, the owners can block or prioritise traffic. E.g. connecting to the internet via Google would make all Google services fast and free, and everything else unavailable unless you pay.

This already happens on a smaller scale; service providers such as VOXI will give you an unlimited data allowance, as long as you’re using it for social media. While on the surface this is a good deal, all it does is pump more data into big tech, who already hoard it to support their own interests. If the ‘free internet’ only consists of Facebook, Amazon, and Google, where does that leave everyone else?

It limits power and choice for the user, and it makes innovation more of a challenge for smaller companies. In other words, it becomes a data governance issue.

What this all comes down to is the regulation of the internet. Should this be pursued or is it a dangerous game? On the one hand we have the systematic, private regulation via big tech. On the other hand, there’s regulation at a government level. The question is: who do you trust more with your data?