It’s the thing that turned the likes of Facebook and Google into giants — free services are also advertising networks

Behavioural advertising does what it says on the tin: it’s advertising which is based on your behaviour. Have you ever seen an ad for something you need right now? Or promoted content that actually changes your mind on something? That is behavioural advertising.

This term has been coined because ‘targeted advertising’ is not enough anymore; before, targeted ads were more contextual. E.g. you look at some football results on BBC Sport and see an advert for football boots.

The way we are targeted with ads nowadays is a lot more invasive, because it’s based on your behaviour. This goes beyond just browsing — by using apps that make your life easier such as maps, relaxation and sleep apps, mensural trackers, and specialist coffee shop finders, you are constantly producing data that is used to advertise you even more products.

The things that this article will seek to explain are how companies track your online behaviours, and how that data is taken and used to make adverts.

How the tracking actually happens

So, before anyone can know what advert to show you, they have to know more about you. That means: collecting data. Companies will employ as many methods as they can think of to gather as much data as they can about you, put it together, and compare it with everyone else’s data — all in the name of serving the most ‘relevant’ ads possible.

There are three main methods that track your online behaviour:

1. Persistent Cookies

These kinds of cookies are designed to stay in your browser unless you actually make the effort to delete them yourself. They are commonly used to keep you logged into websites — so that you don’t have to keep logging in as you navigate from page to page, and so that you can stay logged in even if you browse away.

☝️ The important part about persistent cookies is that they uniquely identify you in some way — this feature is necessary because they are used to verify logged-in users.

Now, the other important part about these cookies is how they are used. What I’ve described so far is cookies dropped by the first party. So, if you’re on your favourite blog site — let’s call it Bloggy for the purposes of this article — cookies they drop for things like keeping you logged in belong to Bloggy; they are the first party.

Bloggy could, however, be dropping numerous cookies from third-parties without asking your permission. And this is where the fiendish tracking game begins. How do Bloggy do this? There are so many ways to sneak third-party cookies through. A very common way was just recently found to be unlawful by the EU Court of Justice. Here’s how it’s done:

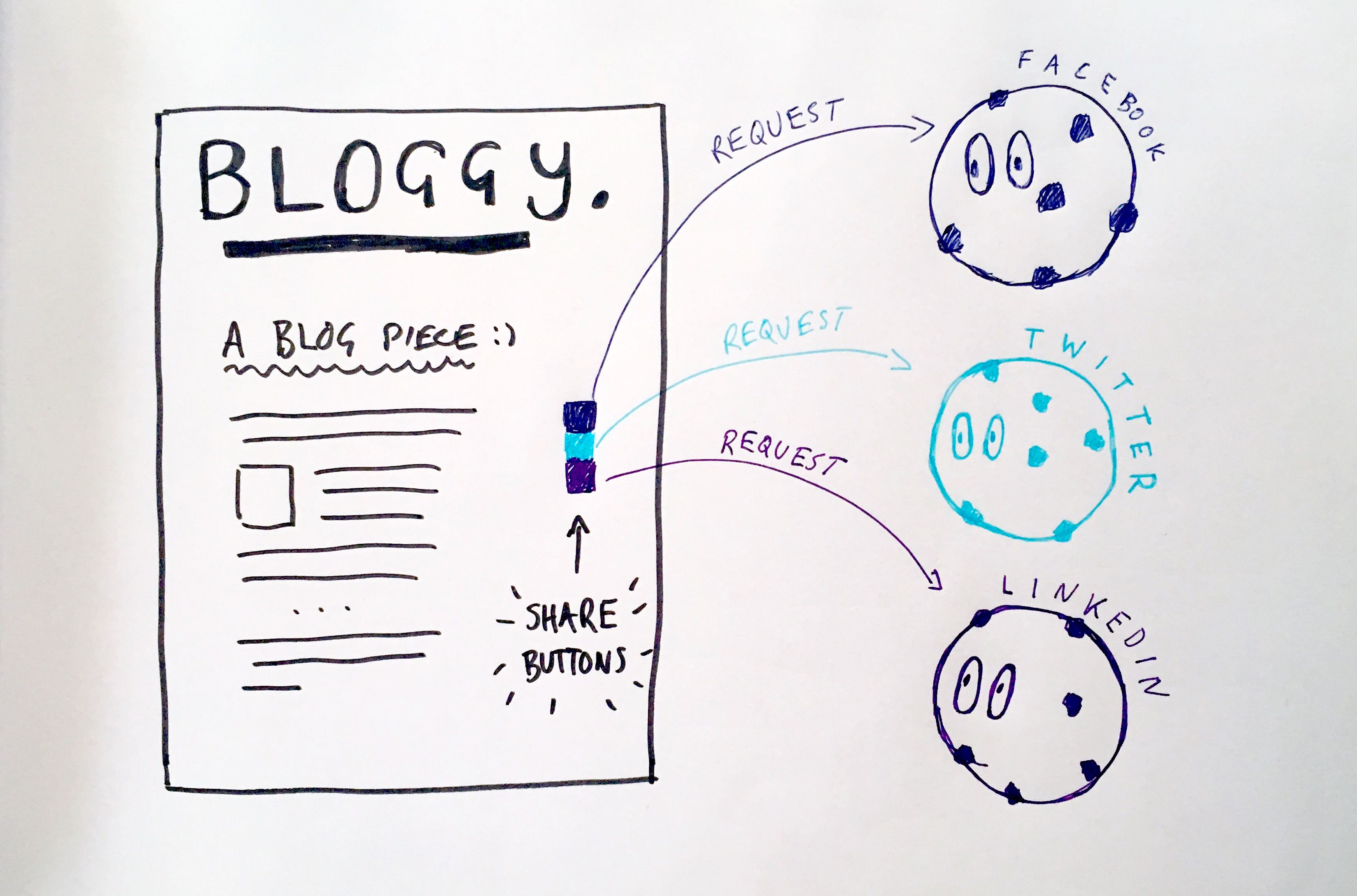

- Every article on Bloggy has social media buttons for Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn; this is so you can easily share an article on one of these platforms

- In order for Bloggy to even display these buttons, they need to ask each platform to send it over from their servers

- So that means, while you’re on Bloggy, they are making requests to Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn’s servers, regardless of whether or not you click on any of these icons.

In other words: if Bloggy were a house and you were a guest there, the owners are saying Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn are welcome to come in and do whatever they want — including forcing you to eat some cookies.

How innocent share buttons on Bloggy produce cookies… with eyes

How innocent share buttons on Bloggy produce cookies… with eyes

Whether or not you have an account with any of those platforms is actually irrelevant — they will put persistent cookies in your browser via Bloggy either way. Just like cookies that keep you logged in, these cookies contain unique identifiers. This is how companies build and maintain advertising profiles.

A lot of the time the cookies are just there in the background, with no visible presence on the site, adding no value for the user.

They may not know your name, but they know you are the user who visits Bloggy everyday at 5pm and reads for roughly half an hour. So abstractly, Facebook, Twitter and LinkedIn could know you as something like ‘user-xyz’.

So let’s say you then browse away from Bloggy to read some news and then to buy cat food. Facebook, Twitter, and LinkedIn are very good at making sure their cookies are present on as many websites as possible so you inevitably bump into them pretty much everywhere you go online.

A quick scroll through all the third-party cookies Forbes has — Facebook, Google, Twitter, and LinkedIn are all present.

A quick scroll through all the third-party cookies Forbes has — Facebook, Google, Twitter, and LinkedIn are all present.

So all these other websites you visit are, just like Bloggy, making server requests to many third-parties at a time, verifying you as user-xyz. “Pet owner” and “votes Labour” has now been added to your advertising profile based on what you just bought, and what you just read.

☝️ Another important note to remember: what I have just described is just one way in which cookies are secretly dropped into your browser. Hiding them behind sharing and like buttons may seem passive and underhanded but a lot of the time the cookies are just there in the background, with no visible presence on the site, adding no value for the user.

The next two methods achieve the same effect as all of this, but are harder to block — because they are not cookies.

2. Browser fingerprinting

The thing about cookies is, they are specifically used to identify you, even if they aren’t the tracking kind (e.g. to log in to a website). Savvy users and sophisticated browsers often block and delete cookies. So another way to built up user-xyz’s advertising profile is browser fingerprinting.

So we learned that Bloggy was dropping third-party cookies from social media sites, without really asking — they also load scripts from third-parties. These are snippets of code which when executed, perform an action. In this case, the execution is triggered by you visiting Bloggy, and the action is to (in the background) collect data about your browser.

This sounds like nothing, but the data these scripts are able to collect include things like:

- your location

- your IP

- what extensions you have (including ad blockers, ironically)

- what fonts you are able to display

- screen resolution

- hardware you have

Each of these data points vary enough from user to user that they can essentially fingerprint your browser. Data will be matched and compared until they narrow down that you are user-xyz. As with cookies, once they know who you are, they know where you’ve been, and what devices you use.

3. Tracking pixels

Again, the goal of tracking pixels is exactly the same as cookies and browser fingerprinting: to collect data, learn about you, and use that for ads. Think of a pixel (any pixel, even the non-tracking kind), as a unit of measurement for digital images; an image could be 500x200 pixels — that’s not all that big, so a single pixel is more or less invisible to the naked eye.

The most infamous is the Facebook pixel. Bloggy definitely use the Facebook pixel — Facebook probably knows more about the human race than anyone else. Therefore, they know best who should see what ads. Here’s how it works:

- You visit Bloggy, and they load up their site + one pixel provided by Facebook

- Just like with the social media sharing buttons, Bloggy has to ask Facebook for that pixel by making a request to their servers

- Once again, the Bloggy house is open, and Facebook are in.

- Ah, there you are user-xyz. Reading Bloggy articles again. Noted — on the profile it goes.

This pixel is invisible, because it’s just a singular pixel that blends in with the rest of the Bloggy. Your ad blockers, or your browser’s cookie blocking capabilities will not even notice it because you can’t ‘block’ a pixel.

And that’s just web…

These three tracking methods are only a portion to what you’re exposed to, because these are limited to general browsing (via Chrome, or Firefox, or whatever browser you use). Other, similar tracking technologies are also employed in the apps you use, giving third-parties insight on what games you play, what utilities you use, and what content you stream.

How this turns into adverts

Fast-forward one year: you’ve bought a lot more cat food, read a lot more news, and interacted with thousands of products and services via your laptop, phone, and TV. User-xyz’s advertising profile is hefty. After learning about how all the data collection and tracking happens, you likely have a very burning question…

Why would Bloggy, my most favourite blog, just let all these third-parties in?

The answer is simple: money. You get to read Bloggy for free, so Bloggy do what they can to make money out of your data. Or rather, the data associated with user-xyz.

They do this by publishing ads 👀. Blogs have lots of eyes looking at them, so naturally advertisers want a piece of that. Bloggy will sell ad space, and publish ads that are ‘personalised’ for you.

So Bloggy are a publisher, make money from advertisers buying ad space for their behavioural ads. The next question is…

What is it that actually makes these ads on Bloggy… ‘behavioural’.

Great question (I’m aware that I asked the question, but it’s still a great question) — this is where advertisers and publishers (like Bloggy) come together. The things that enable these ads to exist are…

✨ ADVERTISING NETWORKS ✨

Please remember that term — ad networks are what make all of this possible. The next thing to remember is that Facebook is an ad network first, and a social media site second.

Think about it: it’s a platform that exists to literally learn everything about you: who your friends are, what events you go to, what groups you interact with, how happy you are, how sad you are, how anxious you are. We willingly hand over all these things about ourselves via our Facebook profiles — and they’ve been gathering that data since 2004. Just think how much they’ve learned about the human race in that time. Knowing humans this well really helps when it comes to targeting them with adverts.

Facebook is an ad network first, and a social media site second

Google are also an ad network: your searches, your emails, your map data — this all paints an excellent picture. This is why this kind of advertising is called behavioural. Your interactions with Google and Facebook products alone have created a dense and detailed profile for user-xyz. Your advertising profile likely contains details as intimate as your sexual orientation, political alignments, and religious beliefs.

This overwhelmingly rich tapestry of data about consumers would give anyone with access great influential powers — this is why advertisers pay through the nose to use ad networks. So I guess the next question is…

How do ad networks… work?

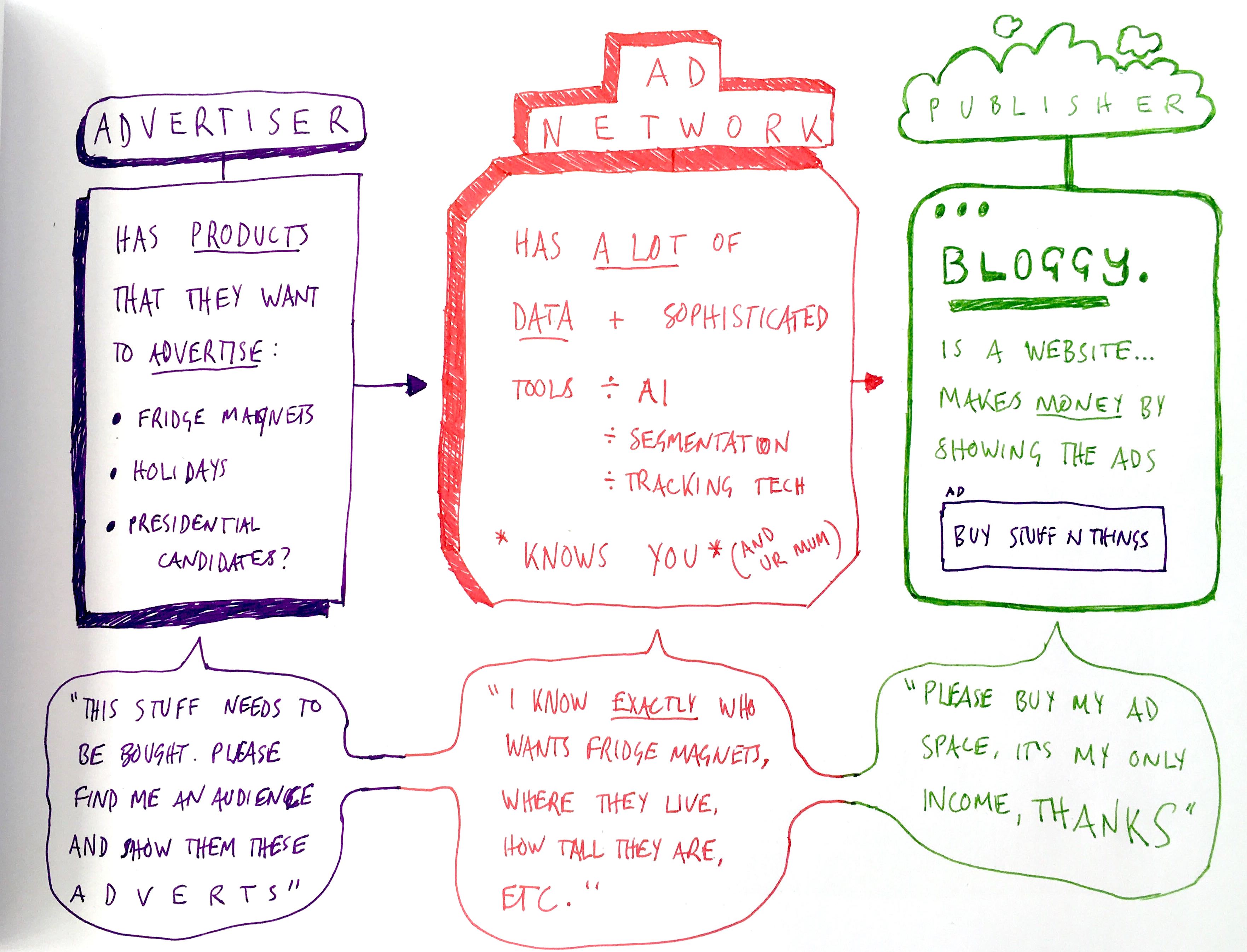

The basic function of an ad network is to act as the connecting point for advertisers and publishers. So it flows like this:

Advertisers have adverts that they would like to show people → they give those adverts to ad networks who have all the data and resources to serve ads to the correct audiences → ad networks then distribute ads to publishers who show the ads to just the right people.

How ad networks facilitate behavioural ads

How ad networks facilitate behavioural ads

So ad networks have two key things that advertisers don’t have:

Thing One: user data, consolidated into advertising profiles, and cleverly segmented into very specific audiences

Thing Two: very sophisticated internal tools to aggregate data, and get as much out of it as possible — including using AI to make inferences about users. E.g. moving away from watching your behaviour, to simply predicting it.

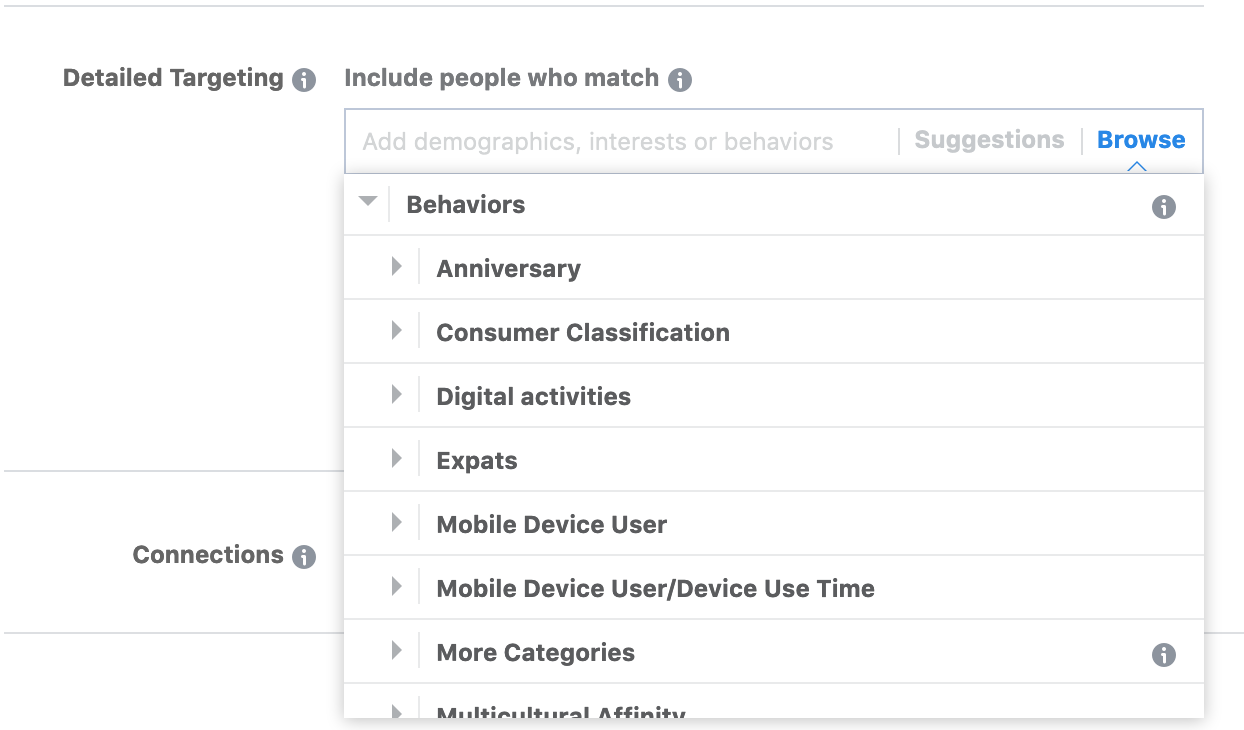

So, all an advertiser has to do is tell the ad network what product they are trying to sell, and who they want to sell it to. So for example, Facebook’s advertising tools include things like ‘detailed targeting’. When they say detailed, they mean details you probably never would have considered.

Showing the drop down of subcategories under ‘behaviours’ in Facebooks ad targeting tools

Showing the drop down of subcategories under ‘behaviours’ in Facebooks ad targeting tools

With Facebook’s tools, you can define your audience within three major categories: demographics, interests, and yes, behaviours. The latter includes looking at stuff that people have tended to do in the past, and using that to predict what they might do in the future.

That’s because, with segmentation tools this powerful, an advertiser can specifically advertise to:

- Someone who’s just moved back to London from Brazil and likes going to the Gym — they might want a gym membership.

- Someone who’s in a relationship, their partner has a birthday coming up, and neither of them have been on holiday in ages — show them a deal for two at this spa

- Or what about user-xyz? Has a cat, spends most of their time at work, cares about the environment — maybe they’d like sustainable pet food delivered to their door.

So… I will just be the subject of tracking forever, and the data I produce will be used to target me with ads for as long as I live?

No, of course not. Because — unexpected twist — with the advertising technology available, your data could contribute to behavioural ads long after you die. Hahaha yes, what a nightmare. How is this possible?

Because of very advanced guessing techniques made possible by artificial intelligence. Why bother continuing to learn more about the human race when you can get machines to do it for you?

That’s why there’s almost no need to improve tracking technologies anymore — what we have now is an ad network race to develop the best AI: a super-computer guessing machine that knows who you’ll vote for in the next election before you’ve really decided yourself.

Ad networks don't have to watch you anymore, because with this digital projection they already know what you're going to do next.

So you stopped feeding the advertising profile for user-xyz a long time ago — machines are feeding it now. They took the profile, learned from it, compared it with other profiles, and have made something completely new — user-xyz has actually disappeared, and in its stead is an online, digital projection of someone who talks, thinks, and behaves almost exactly like you. Ad networks don’t have to watch you anymore, because with this digital projection they already know what you’re going to do next.

You and people like you probably have the same taste in pineapple

You and people like you probably have the same taste in pineapple

With this model an ad network does not necessarily need to ‘know you’ but know who is like you. That way, if you buy a decorative gold pineapple you will of course not receive any ads for another one — but people who are your age, also have a cat, and also read Bloggy will likely see the ad because they are just about enough like you to also want a decorative golden pineapple.

Accurately guessing your behaviours on a mass-scale then leads to things such as loyalty predictions: how likely it is that you’ll abandon a brand for another one. In cases like this, advertisers and ad networks will either push alternative brands, or try and make the current chosen brand more appealing with sweet deals. It’s possible that we no longer decide things anymore — we just passively rely on machine recommendations.

In this way, behavioural advertising breaks the barriers of data privacy, and moves straight into the abject persuasion and influence of internet users.

Are we doomed or is there anything I can do?

We are not necessarily doomed, and there is some stuff you can do. But it’s important to note that while you can do as much as possible to exercise good data hygiene, there’s no such thing as wiping the slate clean — even if you throw all of your devices in the sea and go live in the woods.

Some recommendations for having a little more control instead of just flat out being controlled:

- Use browsers such as Brave or Firefox: they have excellent privacy settings — even the defaults are pretty good. They let you manage cookies, and even block other tracking technologies.

- Try a couple of add-ons such as Privacy Badger which blocks trackers, and also learns what not to block, and uBlock Origin (do not confuse with ‘ublock’) which is much more than just an ad blocker

- Use private browser windows where ever possible — every browser has this capability

- There are quite a few tools out there that can help with online experiences; from understanding dark design patterns to understanding privacy policies

- Always question what is ‘required’ of you when using products or services. E.g. anything that requires an app to ‘set up’ like these Bose headphones. Most of the time nothing ‘needs’ an app — it’s just an excuse to have access to your phone or device.

Most importantly: free apps and services may not cost you any money, but your digital life will become easier as soon as you start to look at it as a trade. Reading the terms of service on any product you interact with will outline what you are trading in exchange.

These recommendations are not meant to help you avoid doom — they are meant to help all of us get to a more fair and transparent internet, where data flows freely and ethically, and not into the hands of greedy tech giants.