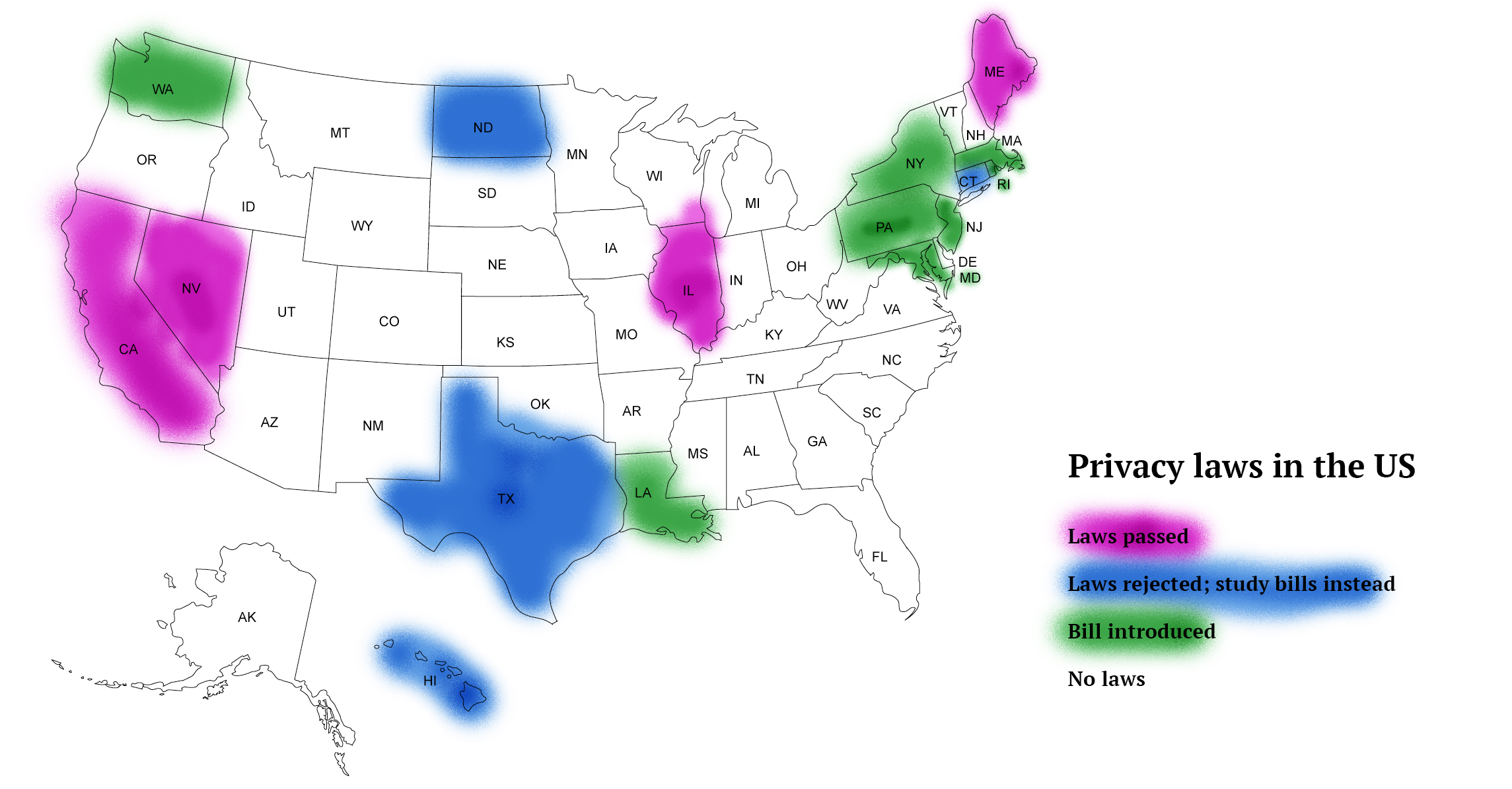

So far 2019 has seen a surge in US bills relating privacy at a state level — which states, and what bills?

State laws in the US are usually more specific than federal laws because they are sort of plugging the gaps that federal laws may not have accounted for. It’s also much harder to lobby for or against fifty or more separate laws with their own nuances than one general law for the entire country.

Big tech companies with global reach most likely prefer country-wide, or even continent-wide laws (hello, GDPR). But in the USA, it’s much quicker to pass state laws, so following the EU’s regulation, various states have been piping up about putting together their own versions.

Which states have passed laws?

California

There’s been a lot of talk about the California Consumer Privacy Act recently — it will go into effect on the 1st of January 2020 and it’s pretty punchy. It centres around giving consumers a comprehensive set of rights over their data. No other US law in effect has such emphasis on data rights.

What this law means for the state: California residents will now have some shiny new rights; they will have the power to make certain requests to businesses, such as deleting their data, or stop it from being sold on. It’s important to remember the businesses effected could be based anywhere — this law applies if they have customers in California.

The penalties: a business could get fined $2500 per violation. Consumers can also take businesses to court if they find that any of their rights have been violated.

Nevada

Interestingly, Nevada already had an online privacy law, but this year they decided to update it so that businesses now must allow customers to opt-out of the sale of their data. Like the CCPA in California, they also have to disclose what types of data they collect, and for what purposes. Nevada does not have a solid set of data rights for consumers. This updated legislation is actually already in effect (as of 1st of October 2019).

What this law means for the state: basically, ever so slightly more control over the flow of data for Nevada residents, in that they are now allowed to ask a business to not sell their data anymore.

The penalties: a fine of up to $5,000 per violation, and temporary or permanent injunction

Maine

The regulation in Maine is much more focused on internet service providers (ISPs) — and it only applies to providers operating within the state. The regulation reads that ISPs may not “use, disclose, sell or permit access to customer personal information” without prior consent. ISPs will also be prohibited from making their services unavailable or more expensive to those who do not consent to their data being used in this way.

This will come into effect on 1st June 2020

A couple of things:

- This regulation defines ‘personal information’ pretty well, but perhaps not as detailed at the CCPA. However it covers enough to make sure ISPs are more limited in how they can engage in behavioural advertising. E.g. browsing history, device information, health information.

- To get consent ISPs will have to provide “clear, conspicuous and non-deceptive notice at the point of sale” as well as on their website — would be interesting to see how that manifests, and how ‘non-deceptive’ is interpreted.

What this law means for the state: it’s pretty good for consumers, because it’s based on opting-in: the default is to keep personal information more private. But, it’s strange that this is restricted to ISPs. Sure, they have first-hand insight on people’s internet activities, but there are plenty of non-ISPs that can get their hands on such information, and more.

The penalties: they don’t seem to have those yet…

Illinois

I’m including Illinois because they have had a Biometric Information Privacy Act since 2008, to regulate the collection of biometric data (e.g. your face, your fingerprint, etc). The supreme court made an important ruling earlier this year regarding this law: Six Flags took the fingerprint of a 14-year old without parental approval, and argued in court that the family suffered no damages because of this. The supreme court ruled that no one had to suffer damages for this to breach regulation:

“A person need not have sustained actual damage beyond violation of his or her rights under the Act […] Whatever expenses a business might incur to meet the law’s requirements are likely to be insignificant compared to the substantial and irreversible harm that could result if biometric identifiers and information are not properly safeguarded.”

What this law means for the state: this ruling has set a precedent; the courts have said that ‘damages’ are basically irrelevant when it comes to penalising businesses. It’s a simple message: just don’t collect biometric data without consent.

The penalties: private right of action — all you can do is sue. A class action involving this regulation against L.A. Tan Enterprises, Inc had a settlement of $1.5M in 2016, which was between $125-150 per claimant.

Which states have tried and failed to pass laws?

I think it’s important to have a quick glance at states who are thinking about the privacy of their citizens but for whatever reason have not managed to get a law passed. The following states are instead doing study bills and advisory boards where they spend time learning about other state laws, and coming up with best practices around privacy.

Connecticut seem to have tried to pass the most laws out of the following state. Here are some that failed:

- Stop retailers using facial recognition for marketing purposes.

- Stop social media sites accessing a user’s contacts for marketing.

- A requirement for internet service providers to register with the state, pay a fee, and essentially be treated like a utility. This would have been state-level net neutrality.

Texas wanted to pass one law about limiting personal information collected from certain businesses, and another to regulate biometric data usage with financial institutions.

North Dakota wanted to apply regulation to data brokers and punish them with a penalty.

Hawaii are waiting to hear back about a law that wold give consumers certain rights to request what kinds of data are collected by businesses. The governor vetoed a law saying that the sale of location data collected from satellite navigation was not allowed without consent.

👉 To conclude it’s clear that each state is thinking about privacy a whole lot more, and each have their own priorities within that. Even though these laws are just at a state level, they have the potential to effect the entire country and beyond. This is why Facebook and Google have tried, over and over, to fight the biometric law in Illinois.

The California regulation is the most comprehensive, and affords the most rights to consumers; once in place it may inspire other states to do the same which could spark massive changes in the US data privacy landscape.