Nowadays things like dictionaries are digitised and free (if you mean money)

In the dark simple times of pre-internet, if you wanted to know what the word ‘ostensibly’ meant, you had to go to your book shelf (yes that’s right, everyone had one) and pull out a dictionary which you purchased using money (the physical kind made of paper, gross).

Now that we live in the future we use computers to do everything — including dictionaries. Dictionary.com is free to use, but it drops 118 cookies without asking for consent. Among these are tracking cookies from Amazon and Google.

The results from scanning dictionary.com with TrackerTracker. Merriam-Webster drops 52 and Thesarus.com drops 131.

The results from scanning dictionary.com with TrackerTracker. Merriam-Webster drops 52 and Thesarus.com drops 131.

But how does dictionary.com make money out of this? In the web that use today, the way sites like Dictionary.com make money is not from charging users (because we’ve somehow grown to accept that digital content = not worth money), but from collecting data and publishing ads.

Sites like this (including blogs and anything else that serves ‘free’ content) are known as publishers and while they are free to use, they are not free to build and maintain. Therefore: ads.

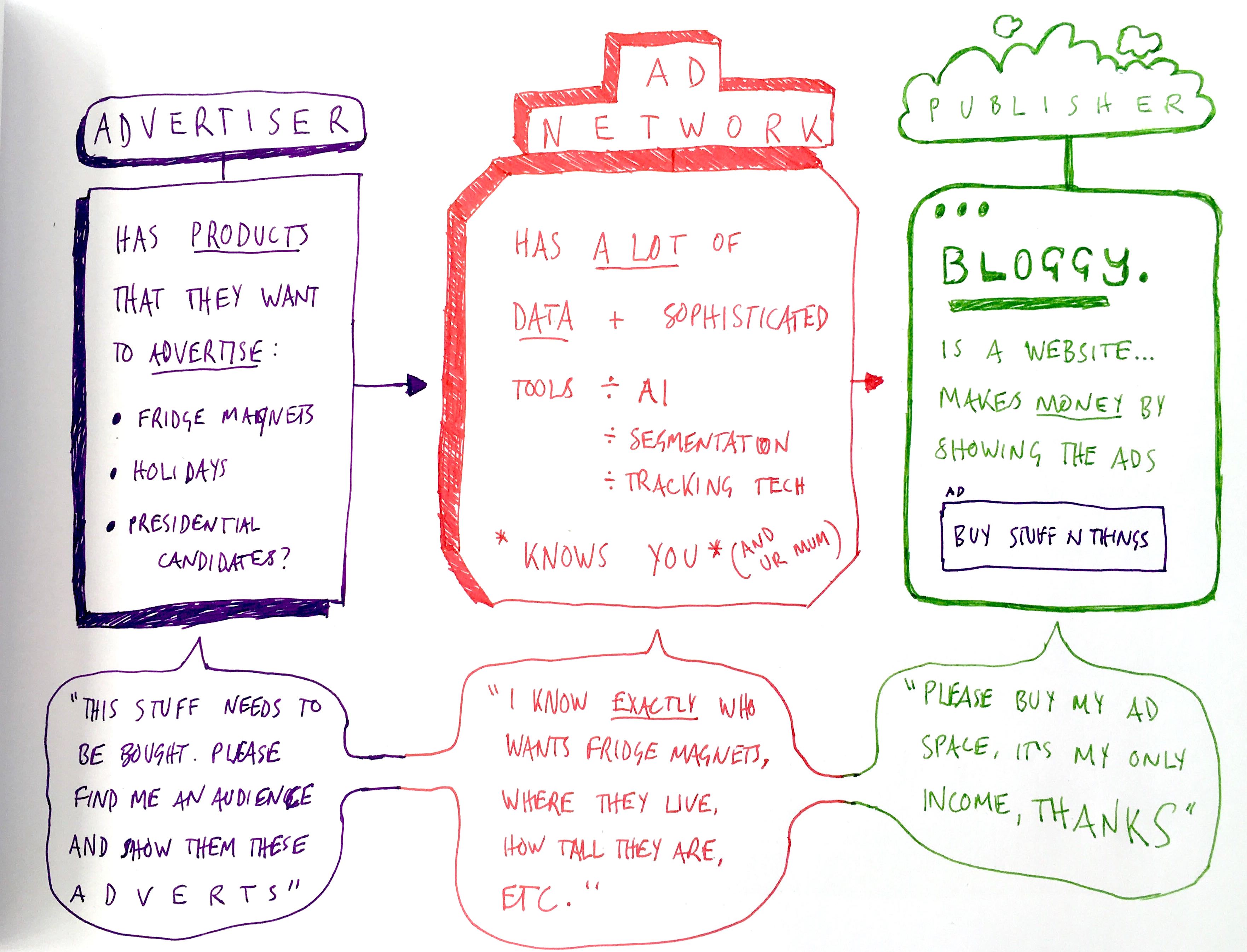

And how is the money even made? This is the ultimate question, and the answer is basically this:

- Businesses need to sell their products, so turn to advertisers.

- Advertisers need to know who these products would appeal to most, so they turn to ad networks (like Facebook or Google) who know what users ‘want’.

- Publishers (like dictionary.com) need money, so make agreements with ad networks to show the ads for money

In case you’re confused, we produced this nifty diagram.

Cookies play an important part in this machine: they are the things that live in your browser, remember things about you, and broadcast those things to the advertisers and ad networks. This is more or less how consumer data flows around the internet; it makes predictions about you that are very accurate because it’s based on your everyday behaviour.

📣 As I type this I can hear each and every reader say, “but I use an ad blocker”. That’s nice, you belong to 30% of internet users. The rest do not block ads — the money is made from that lot. This doesn’t even include mobile browsing — ad blockers on mobile are used a lot less, and are not as powerful. Just think how many random articles you half read on your phone as opposed to your laptop browser.

If websites are free for users, but they still manage to make money, that’s win-win, right?

Not really. First of all, it breeches regulation. Under GDPR, you have to get user consent for any non-essential cookies you set. A ‘non-essential’ cookie is anything that sits outside of delivering the service your site offers. In the case of dictionary.com, that would be giving us definitions of words. That function does not require any cookies at all…

Secondly, it perpetuates a lot of problems — ones that regulations are trying to solve. Dropping cookies without consent lacks transparency, and therefore eats away at user autonomy.

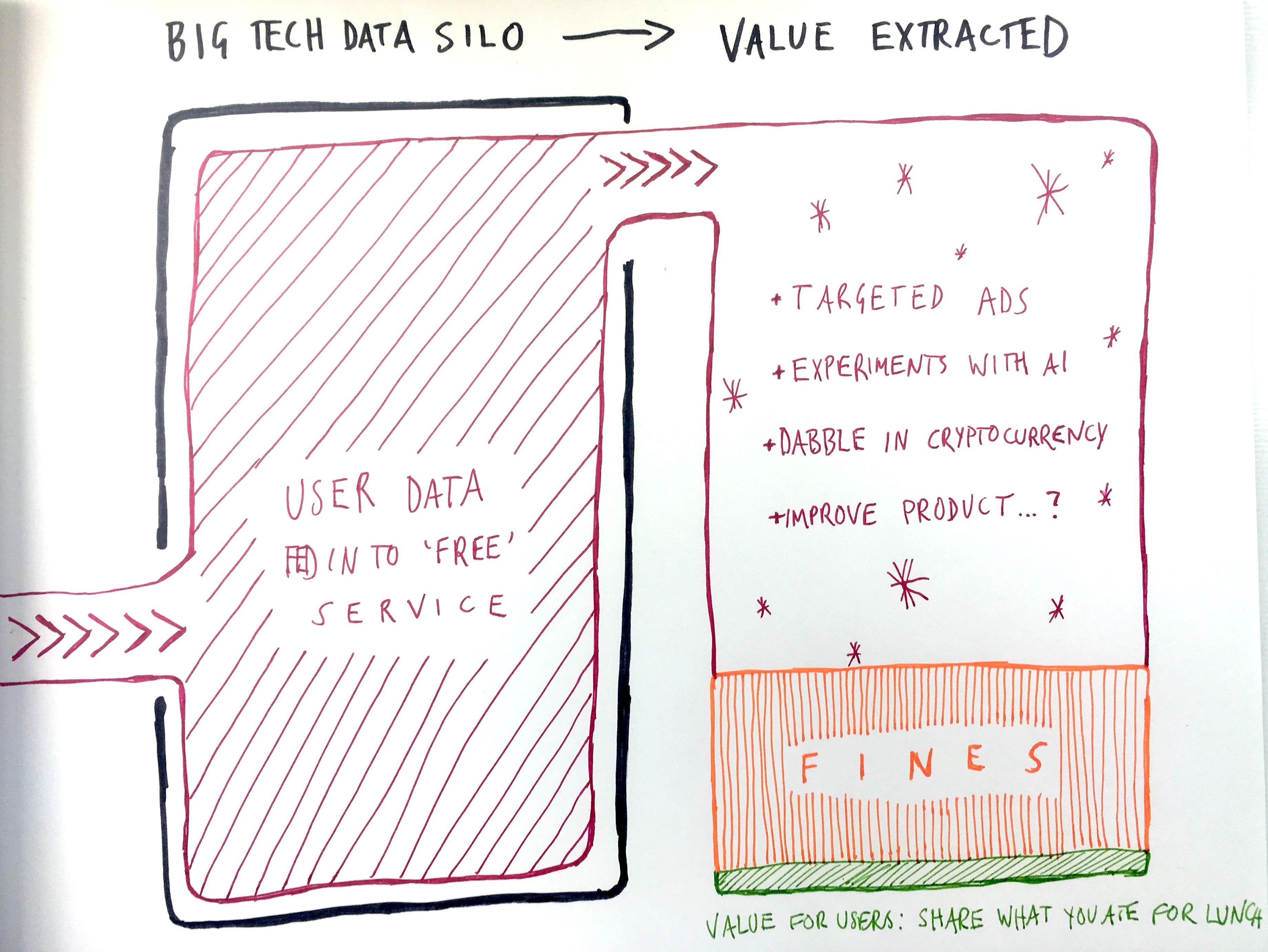

This system also disproportionately benefits ad networks. They are the ones with all the data, and therefore stand to make the most money. Publishers rely on them to make money, and then users get to look at a free site.

But the value you get out of learning what the word ‘ostensibly’ means doesn’t really compare to the value of the millions of ad impressions popular publishers (like dictionary.com) rack up.

Impressions make money. Money makes scary new-age ideas a reality: such as Libra, Facebook’s way of disrupting our banking system, and Google’s TensorFlow, a powerful AI platform used by the military.

☝️ To conclude, dictionaries still aren’t free, you simply pay with something other than money: your data.

To further conclude: now that you probably don’t want to visit dictionary.com yourself, ‘ostensibly’ means: as appears or is stated to be true, though not necessarily so; apparently.