If all your behaviour is recorded digitally every day, so is your health

If you’ve read Incognito before, you may have come across April, our fictional dummy for privacy related experiments. Last time we saw her, she used an app that was putting all her data on a blockchain, making her unable to delete it. We also had a look at what might happen if her data was made more easily accessible to her, the government, and her employer (sucks for April).

Consistently gathering behavioural data on a mass scale has a lot of potential — this data is very versatile, and is used by ad networks to predict what we will do next, so they know what products to sell us.

In April’s case, her behaviour has been changing recently, in the following ways:

🚌 April’s commute time to work is now fifteen minutes longer: she’s started taking the bus instead of the tube. This is clear because she spends the commute either reading articles on Medium or listening to music on Spotify, and the respective use of these apps has gone up by fifteen minutes. How much she spends on her commute daily is the same cost as two bus rides in London.

👖 April just bought some new clothes: lot’s of different basic items like jeans and tops, and they are all two sizes smaller than her last online clothes shop.

👾 April is spending more time watching TV and playing computer games: she accesses her Steam or Netflix accounts every evening and uses them for several hours.

🍻 April hardly ever goes to a different location after work: nowadays she normally just goes home. This has become quite obvious from her passive location data — she hasn’t used CityMapper or Google Maps to calculate any new routes and she hasn’t responded to any Facebook event invites for the last couple of months.

Interesting… what can we glean from all this without actually asking April directly?

- April is spending less time socialising, and more time at home. Perhaps she just wants to be alone, or has less money to spend on drinks or dinner out at the moment.

- She’s buying smaller sized clothes which suggests she’s lost some weight.

- She’s also taking a different route to work, even though it takes longer. Taking the bus is cheaper — it’s possible, again, that she’s trying to save money. The bus, especially when compared to the tube at that time of the morning, is significantly less crowded, and means she doesn’t have to go underground.

An ad network like Facebook or Google may look at this data, and — using what they already know about other people similar to April — deduce that she has become depressed and socially anxious. How is it that we got to this conclusion? Because all data is health data.

Collective behavioural data is one of our most powerful resources.

Okay okay, this assumption about April’s health was a big one to make. But this is exactly how our data is examined: entities who exploit our data, will work to fill in the gaps. You can’t do that with small amounts of data from one person, but data collected over a longer period of time, from a large group of people.

That is how such inferences about health can be made — even without any data that explicitly relates to health. It’s almost like big ad networks go through a process like this:

- Hmm, looks like April’s behaviour has changed over the past couple of months

- We know like 100k other people who are just like April: they are in their late 20s, female, have a full time job, live in London, etc.

- Out of those 100k people, the ones who behave like this seem to suffer from depression — it’s a good chance April suffers from depression too, then.

Creating inferred health data is particularly intrusive and terrifying, because these inferences are being made by big tech companies as opposed to, you know, qualified healthcare professionals.

Inferences about April's health are being made by big tech companies as opposed to qualified healthcare professionals.

If April is indeed depressed, it’s possible that she’s unaware — but hints could trickle through via behavioural ads: “Come to our one week yoga retreat to unwind and learn about mindfulness.”

What options does April have now?

Let’s see, I’m pretty sure she doesn’t want to accidentally find out that she might be suffering from a mental illness via a complex pattern of ads and recommendations. Nor would she want anyone, except an actual doctor, to give her this news.

Cool so, I guess she should stop sharing her health dat- oh yeah, right… she doesn’t share health data at all. It’s companies who passively track our daily behaviours through our various devices, who should stop making guesses about her health.

Is April now just trapped in a world where Google will make money from peddling life-extending products because they know when she's going to die?

Is April now just trapped in a world where Google will make money from peddling life-extending products because they know when she’s going to die? Well, the answer to that is complex and speculative — big tech data practices are black boxed, so it’s hard to say ‘how much they know’.

As we continue on our forward march through linear time, big tech will expand the surface area on which they can capture data. Where before it was simply through phones and computers, nowadays behavioural data is collected via anything from your TV, thermostat, or any other smart devices you use.

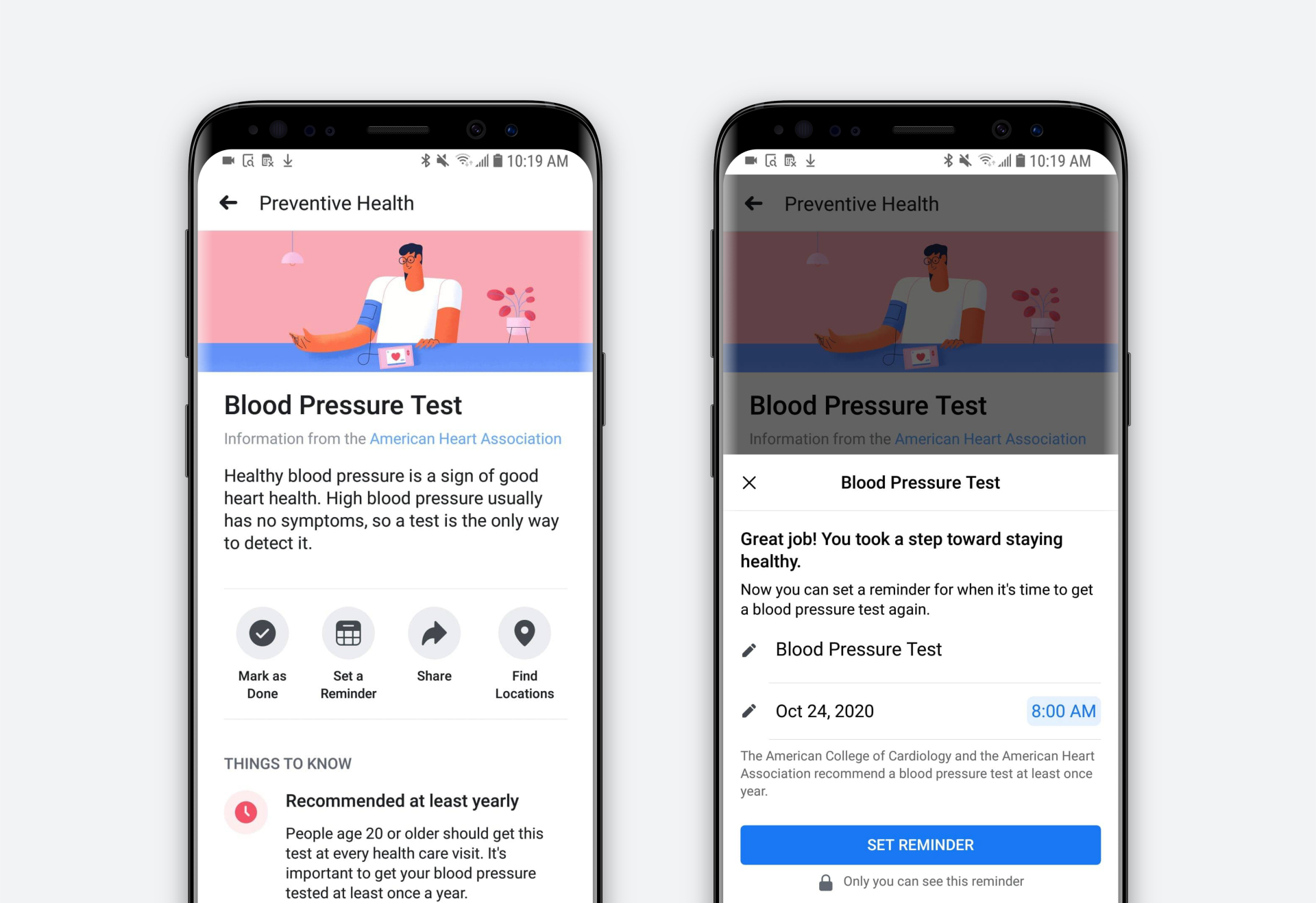

Facebook’s health tools — giving them access to your blood pressure

Facebook’s health tools — giving them access to your blood pressure

For instance, things like the Facebook Portal and an Amazon Echo record your voice, your face, and the way you move around the house — this is biometric data, another entry point for big tech to learn more about you. I try to keep a limit on this by owning no smart devices besides my phone.

This is exactly why Google recently acquired Fitbit, and why Facebook have launched healthcare tools — even though all data is health data, capturing it first hand is easier and more efficient. And this kind of health data is arguably the most valuable, because it pertains directly to our own mortality: the very thing we care about the most.