Here’s how Big Tech’s main players are getting their privacy messaging wrong…

When the GDPR bomb finally dropped in 2018, there was a desperate scramble among Big Tech companies — whose business models revolve around the exploitation of user data — to make some changes. But are these changes only cosmetic?

This falls under what I like to call the privacy promise — the persistent messaging we get from Big Tech about how much they value our privacy.

Google’s privacy promise is about control

Google’s privacy promise **is that you’re in control of the data you produce by interacting with their services: you have the power to look at it and delete it. Sundar Pichai has recently come out with the message that “privacy is for everyone” and “not a luxury good”.

🤔But Google’s privacy controls are buried deep within their systems — how many screens in do you have to go before you can actually ask Google to stop logging your most visited locations via Google Maps?

Why is the onus of privacy management sitting solely on the user?

This somewhat dampens the promise of privacy being under our control. This also begs the question: why should we be the ones to control it? Why is the onus of privacy management sitting solely on the user? Surely it’s the vendor’s responsibility to ensure the data they process is kept private — despite their messaging, they are indeed the ones who have ultimate control over this data.

Their messaging of ‘control’ is also a wonderful distraction from what they do best: use your data for advertising. There’s not much talk coming from Google on how to ‘control’, or even just understand, the breadth of information that is shared in order to show you personalised ads.

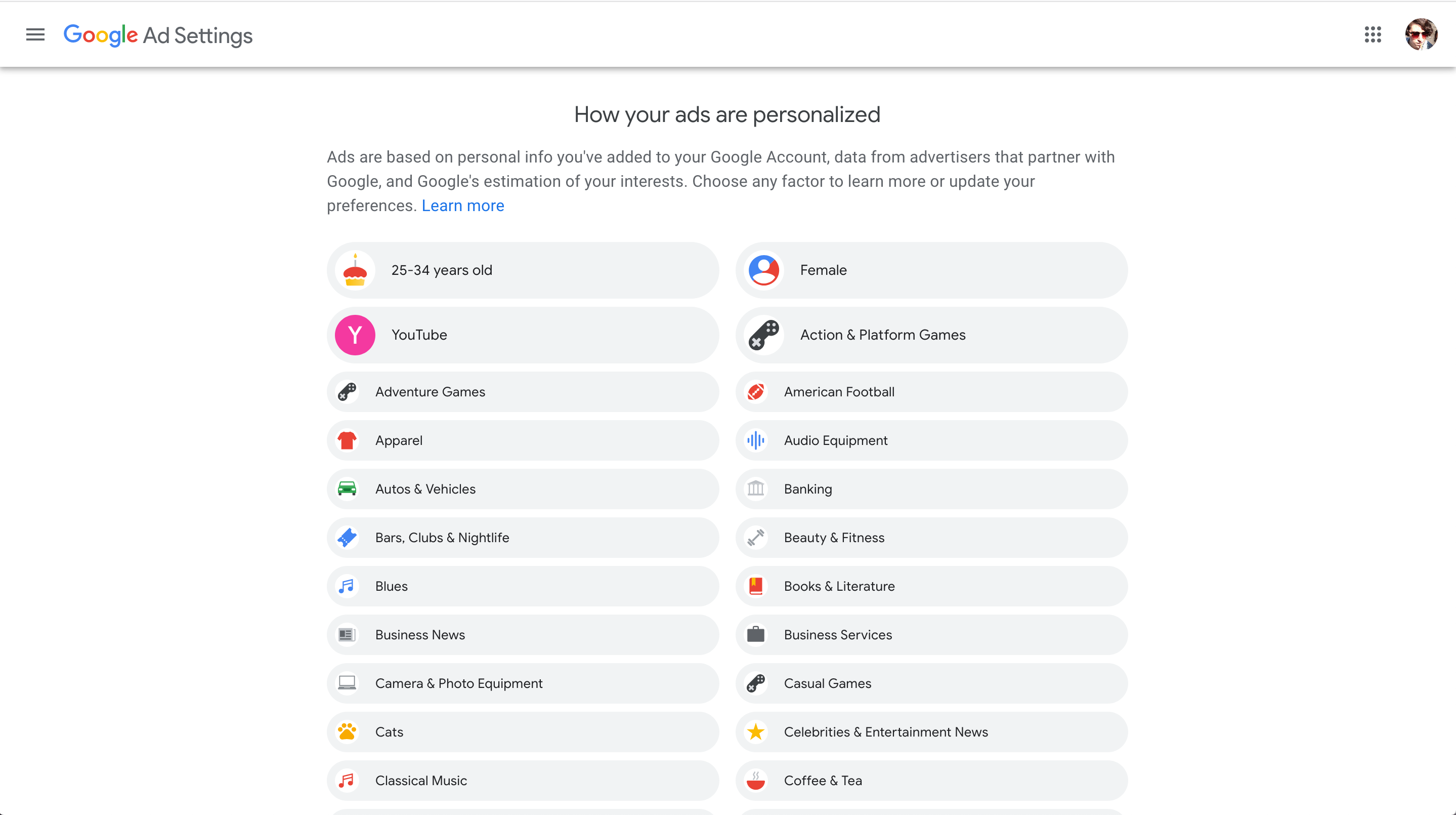

If you want to flat-out turn Google’s ad personalisation off, visit adssettings.google.com

This is how your ad settings look. You can either individually select things to turn off or just blanket turn everything off. There’s no information on how this data was gathered, and exactly how it’s being used…

This is how your ad settings look. You can either individually select things to turn off or just blanket turn everything off. There’s no information on how this data was gathered, and exactly how it’s being used…

Facebook’s privacy promise is about private interactions.

Facebook’s privacy promise focuses on championing private interactions, and how much control you have over who can see what you share on Facebook. This is not dissimilar to Google, because these controls barely scratch the surface of what it means to keep data private, and are also a distraction from Facebook’s ad network.

Private interactions have almost nothing to do with maintaining the privacy of your users.

Their messaging consists of a celebration of this so-called ‘living room’ feel of social media: smaller group interactions as opposed to the bulletin-like announcements of the news feed. During F8 Mark Zuckerberg boasted new features such as a ‘close friends’ tab, and end-to-end encryption.

☝️I cannot stress enough how end-to-end encryption should not be a feature you show off about — it should simply be default. What’s more, as 2019 comes to a close, Messenger is still not end-to-end encrypted by default. (To enable encryption, tap on your profile icon in the top left of the app, and scroll down to ‘secret conversations’).

Facebook’s promise centres around the pleasure of private interactions — but private interactions have almost nothing to do with maintaining the privacy of your users. It also has nothing to do with Facebook’s participation in passively tracking you around the internet.

What do I mean by ‘passively tracking you around the internet’? Well, if you pay a casual visit to buzzfeed.com you will receive 47 cookies without being asked if this is okay — and without clicking on a single listicle. Among these cookies, are Facebook trackers.

![]() The results of a TrackerTracker scan — try it on your own domain.

The results of a TrackerTracker scan — try it on your own domain.

Apple’s privacy promise is that “what happens on your iPhone, stays on your iPhone”.

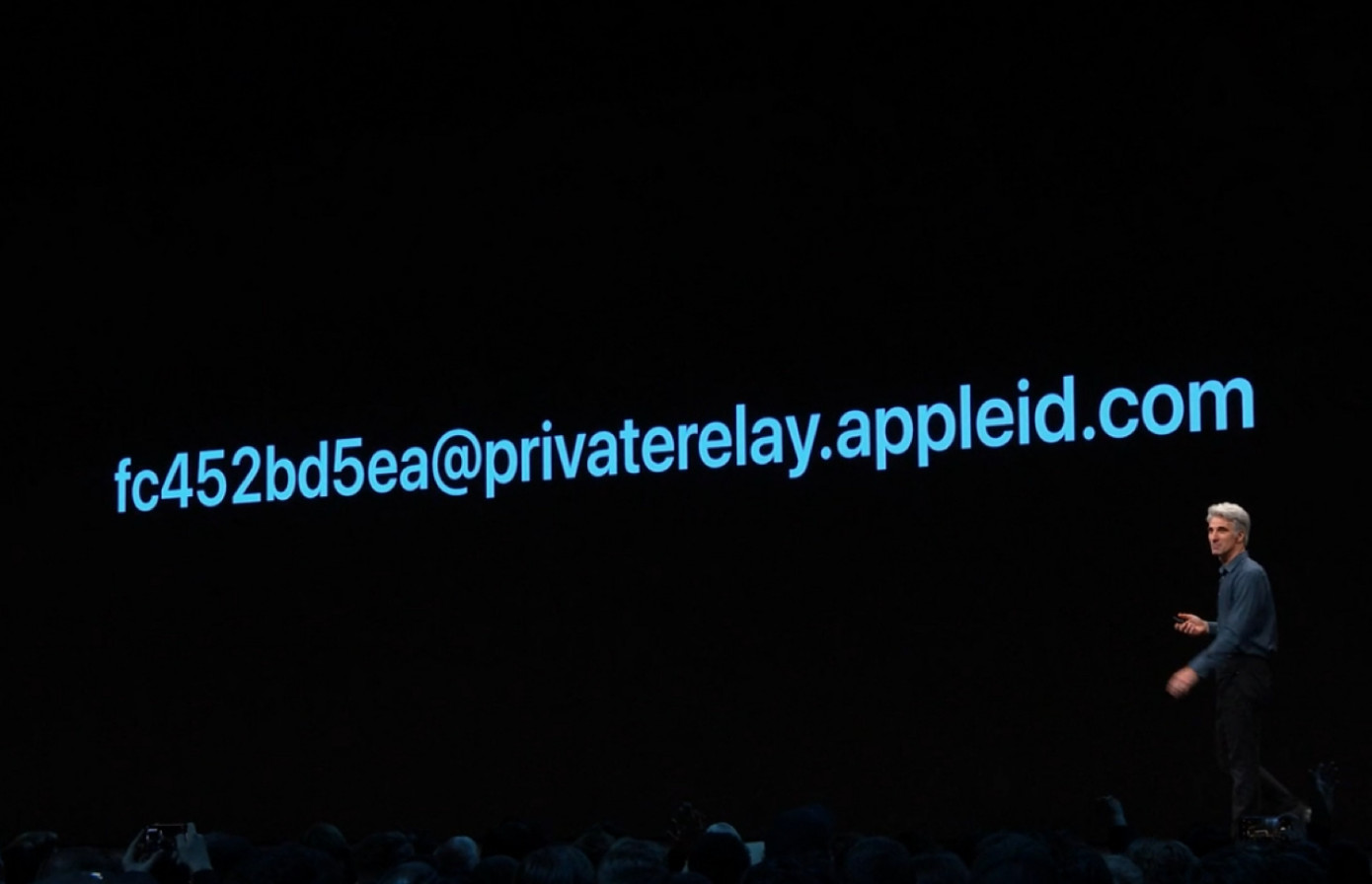

…and this would be true, especially if you consider things such as apple sign-in, where you are authenticated via the device you are using and not by each individual app or website. This is great, because it means **you don’t have to share your email address with every single vendor vying for your attention.

This means an iPhone with nothing but native apps on it is probably the most privacy-centric device you could use… but who on earth relies solely on Apples native apps? The privacy promise dissolves as soon as you install any third-party apps, because Apple have failed to hold other apps to their standard.

An iPhone with nothing but native apps on it is probably the most privacy-centric device you could use

It’s easy to forget that third-party apps are very similar to websites, in that they all have their own privacy policies that you don’t read, and they all engage in the use of tracking technology.

A relay address provided by Apple so you don’t need to use your own.

A relay address provided by Apple so you don’t need to use your own.

Using third-party apps (anything: your weather app, your favourite news app, etc.) therefore enters you into a contract which says it’s okay for ad networks (such as Facebook or Google), data brokers, and small companies you’ve never heard of, to gather your data. Charlie Warzel from The Privacy Project explains how this works:

“The data is transmitted — or in some cases leaked — via software development kits (SDKs). They are essentially developer shortcuts, a set of tools or a library of code that developers can import from a third party so that they don’t have to build them from scratch.” Charlie Warzel, The New York Times Privacy Project

Part of the problem is how useful SDKs are, and who they are provided by. For example, using Facebook’s SDK for your little app takes it’s value from 0 to 30 with almost no effort at all — suddenly you will understand a lot more about the kinds of people who use your app, which helps you improve it and add new features.

The lack of consumer knowledge is precisely what's being exploited — these privacy promises demonstrate that perfectly.

☝️How these SDKs are used also breaks Facebook’s and Google’s privacy promises: liberal (but understandable) use of Facebook’s SDK is exactly how personal data from period-tracking apps gets sent to Facebook without users being asked or notified. Privacy International wrote a report about this if you care to read more.

The privacy promises are not meaningless…

But the meaning they do carry is different to what’s on the surface: these promises, whether empty or not, are indicative of a foundational shift of priorities. Consumers now have an appetite to care about their privacy, but don’t quite understand how to control it — and Big Tech companies are capitalising on that.

However, there are organisations out there who try to help users understand why their privacy is important — some make privacy management tools, which means you can quite literally be a privacy-first business.

During this time of changing ideas surrounding privacy, we have a chance to learn as much as we possibly can about this, because at the moment the lack of consumer knowledge is precisely what’s being exploited — these privacy promises demonstrate that perfectly.

In twenty years time, it’s very possible that we will look back on ourselves and laugh at our daft concerns regarding Google Home secretly recording your conversations, and Amazon’s Ring profiling delivery workers on a facial recognition database. These problems will be a thing of the past, because we would have learned how to tackle the problem of data privacy.