Wow, that decade flew by faster than a self-driving car…

…which is only about 10mph at the moment. If you somehow can remember as far back as 2010, you’ll know that no one was barking at Alexa to turn on the radio, or worried that their doorbell might be wrongfully profiling delivery workers on a facial recognition database. Well now it’s 2020… what’s happened, and how did we get here?

✨ TLDR: in 2010, Google said goodbye to China. Then in 2011 we all said hello to Siri. Facebook also settled their first FTC charge, while Google tried to launch a social network called Buzz.

2012 was a big year for Facebook; they bought Instagram and then made their initial public offering. Then in 2013 Edward Snowden rang the privacy emergency bell and finally taught us that governments besides China also love to dabble in surveillance.

2014 saw the launch of the Amazon Echo and a court settlement that set a precedent for the right to be forgotten. Facebook also acquired two more big fish: WhatsApp and Oculus.

It turns out 2015 was a pretty slow year, so we’re just going to remind you about the young man who got famous from a photo of himself at work, going viral on the internet without his knowledge or consent (he was okay with it in the end). I am of course talking about Alex from Target.

2016 saw two incredible firsts: an entire nation rejected a Facebook product, and the FBI asked Apple for a backdoor. Then, in 2017 the internet shook with the invention of Deepfakes.

In 2018 the world of data privacy was simultaneously created and turned on it’s head. The Cambridge Analytica scandal was reported, and the GDPR came into effect. The events in 2019 were basically products of the previous year: Facebook announced they were pivoting to privacy, and the fight to breakup Big Tech begun.

That’s a lot of stuff… what do we think 2020 will look like?

2010

🙋🏻♀️ Google leaves China; goodbye China.

In 2010, Google had been running censored version of it’s search engine for Chinese users for four years. Search results included a notice informing the users that some results had been removed. The Chinese government of course disliked this very much indeed. The China-Google relationship was basically a constant head to head battle between two surveillance giants. By 2009, Google had more than a third of the search engine market share in China.

Then, a cyber attack coming from within China compromised the Google accounts of multiple Chinese activists. This was the final straw for Google… but they liked being part of one of the largest economies in the world. So they decided to stay in China, except without the censorship bit, which the government found hilarious. China decided they no longer needed Google to compete in the global tech space. They were right.

2011

👩⚖️ Facebook settles some key FTC charges for the first time

In 2009 Facebook brought forward some ‘recommended’ privacy settings. This somewhat marked the beginning of a trend that in 2020, appears to be ongoing: the default settings are always the worst for privacy. The FTC outline the basis of these charges pretty neatly:

“The social networking service Facebook has agreed to settle Federal Trade Commission charges that it deceived consumers by telling them they could keep their information on Facebook private, and then repeatedly allowing it to be shared and made public.”

The charges in this settlement are pretty serious, and was the first time the breadth of Facebook’s back stage activities were truly brought into disturbing focus for everyone to see. You can read the charges here, but shorthand is:

- Facebook made private information (such as a friends list) public, without saying anything or asking anyone if this was okay

- New controls were brought in promising that you could restrict the sharing of information to ‘friends only’, but for some reason ‘friends only’ information was still shared with third-parties

- The promise of not sharing data with advertisers was completely broken

- It was found that other apps had access to much more Facebook data than they needed to operate.

I expect none of this comes as a surprise in 2020.

🐝 Google tries to launch a thing called Buzz

Buzz was Google’s idea for a social network. This time the FTC were taking no chances, and cut them off before they were even able to implement their version of a like button. Buzz worked like this: if you had a Google account, your Buzz account already existed, and therefore all of your ‘contacts’ were publicly available for all other ‘Buzz users’ to see. There was no way to opt-out of this. It’s almost as if they learned the art of deception from their main competitor, Facebook.

🎙 Siri now exists

Actually, Siri already existed… Apple simply acquired it. You could finally talk to your phone, and it would talk back. What does this have to do with privacy? Well, Siri was very much the birth of the virtual assistant; we now have iterations of these that are doing more than listening to commands — they are also gathering valuable biometric data.

2012

Image credit: Bloomberg via Getty Images

Image credit: Bloomberg via Getty Images

📸 Facebook buys Instagram, IPO’s at 16bn USD

This is the year Facebook got more money in the bank, and more users in the database. They went public and were valued at $16bn. Then they bought Instagram for $1bn, just as the platform hit 50m monthly users.

2013

The man we can only see through screens now

The man we can only see through screens now

😮 Edward Snowden blows the whistle

The documents that Edward Snowden released in this year truly began the conversation surrounding individual privacy. Before this, no one even imagined that the NSA were spying on US and foreign citizens to this degree. A tool they’d developed, called PRISM, gave them access to data from Facebook, Gmail, Apple, and Microsoft databases. Snowden described it like this:

“I sat at a terminal from which I practically had unlimited access to every man woman and child on earth”

😳 Sounds like Ed did the right thing. It’s hard to say what this changed practically, but it certainly put new ideas on the map — that we can’t know how much surveillance we are under, because the system has made it that way.

2014

Joining the Facebook pool

Joining the Facebook pool

📣 The Amazon Echo is launched

Just three years after Siri introduced consumers to wonders of voice control, Amazon do their own version with Echo. Thus begins the systematic recording of human voices in everyday situations at a mass scale. Privacy advocates looked on in awe as people willingly installed surveillance devices in their homes; naming your child Alexa was suddenly not an option. None of this mattered though, because now you could control Spotify with your voice.

🤹🏼♀️ It’s a Facebook acquisition frenzy: this time it’s WhatsApp and Oculus

Oh Facebook, you giant innovation hoover, what have you gotten yourself into this time? They bought WhatsApp for a whopping $21.8bn, and, just as with Instagram, they simultaneously gained a heap more users while getting rid of the competition.

But why did they acquire Oculus, who don’t appear to be a competitor in any way? While Oculus didn’t necessarily give Facebook more users, what they did give was more cool technology. Virtual reality opens the door to a million new possibilities — including new kinds of data to study (more biometrics: eye and body movements, facial expressions, gait, etc). It’s all about increasing surface area.

🙅🏻♀️ The right to be forgotten becomes law

In May of this year, Mario Costeja González made a complaint to Google about a link to an article that described an auction on his foreclosed home. This was a debt that he had cleared up, and wanted the information removed from the internet. Fair enough, Mario… but no one has ever asked for something like this before.

The court ruled in his favour, saying that search engines are responsible for what links they surface. This set a precedent: as an individual, you now had the right to ask an organisation to remove data about you from existence. From the 30th of May 2014, Google was required to EU data privacy laws, and immediately received 12,000 requests for data removal.

2015

🎯 #Alexfromtarget

Alex Lee was a sixteen year old who just got home from his shift at Target. He looked at his phone and suddenly had 200k more Twitter followers than he did in the morning, and a request to be interviewed by Ellen Degeneres. Why? A week prior someone took a photo of him at work without his knowledge, and put it on Tumblr — then someone else (@auscalum, which is now a suspended account) put the photo on Twitter, and boom: a new internet sensation was born.

Alex Lee became famous from an invasion of his privacy. His likeness was shared across the internet without his knowledge. He still gets recognised on the street (but it’s okay, I don’t think he minds). This was the first decade in which something like this could happen; this kind of virality was impossible before, and is unlikely to stop being a thing any time soon.

2016

Image credit: Guardia via Getty Images

Image credit: Guardia via Getty Images

✋ India rejects Facebook Free Basics

This decade saw a lot of firsts. In this case, it was the first time a Facebook product was outright rejected by an entire nation. Free Basics is a free portal to the internet, provided by Facebook, for communities that have little or no connectivity. India called it digital colonialism. India just wanted the internet, not Facebook’s version of the internet, where they control what you can see, and process all requests via Facebook’s servers. If Free Basics became ubiquitous in India, Facebook would have first-hand access to all of their browsing — and that is basically a bottomless brunch of valuable data.

Activists set up a site to campaign for net neutrality, and it worked, in part — India does not have full net neutrality, but regulators made it more or less impossible for Free Basics to operate in India.

🕵️♀️ FBI orders apple to unlock phone

By 2016, phones had reached a level of sophistication that meant we were (and still are) carrying around surveillance devices in their pockets. But they were also more secure — only the owner of a phone can actually get into that phone.

This posed a problem for the FBI when they wanted to gain access to the iPhone of the perpetrator of a mass shooting in California. The phone was entirely locked behind a fingerprint, which they could find no way around. So the attorney general filed a court order for Apple to give them a back door.

Tim Cook was furious at this idea; Apple said no. Creating a backdoor for the government would set a precedent — all of the measures they put in place to keep their users data private and secure would just fly out of the window.

2017

Screenshot of video circulated by the makers of Spectre, an exhibition of Deepfakes

Screenshot of video circulated by the makers of Spectre, an exhibition of Deepfakes

😳 Reality falls apart entirely with Deepfakes

This was the year when this part of AI suddenly got really good, and computer-generated faces went from “this is just a blurry mess” to “omg is that actually Jennifer Lawrence?”

The deep learning technology behind deepfakes had become so proficient that almost anyone could superimpose Donald Trump’s likeness onto their dad, if they wanted (luckily no one seems to want to do that). Essentially, it went from being able to recognise individual human faces, to flat out generating them with very little information to go on.

Deepfakes really started a new conversation; they turned someones likeness into data, which was a brand of privacy invasion that no one had really come across before. It essentially forced us to think about this question: if there was a video bouncing around the internet which showed a very accurate, AI-generated impersonation of you — but it wasn’t you — would you care?

2018

🔎 Cambridge Analytica scandal reported

This is it, everybody: the year everything got turned on it’s head. In March, The Guardian reported that a data analytics firm called Cambridge Analytica was harvesting the data of millions of Facebook users. What for? Technically, for whatever anyone would pay them for. But the thing that everyone was upset about: swaying political opinion.

Many believe that the use and manipulation of this data was used to sway the 2016 US presidential election, and the UK EU referendum. The belief is that data was used to run highly targeted political ads to those who were likely on the fence about which way to vote… and push them in the ‘right’ direction.

That aside, it’s still widely agreed that the sharing of that much personal data with a private firm was completely inappropriate and a massive invasion of privacy — Cambridge Analytica should never have had access to it at all.

This event did a lot to open the eyes of the regular internet user to the idea that what they’d been doing over the past few years is tell a private company all their secrets — and that company did nothing to guard those secrets. For many, their trust in Facebook went down the drain, along with their faith in democracy.

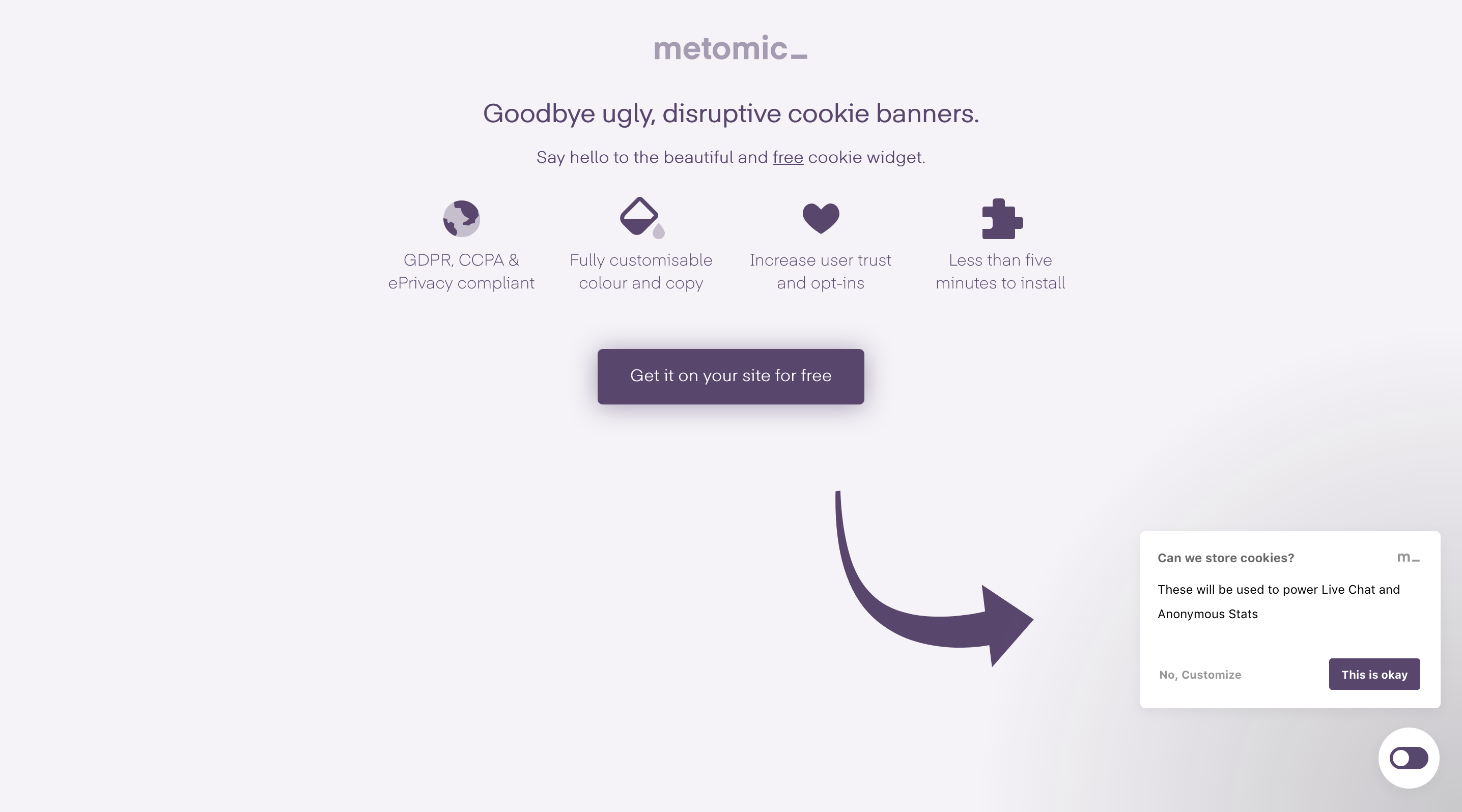

👩⚖️ GDPR comes into effect

With almost expert — but purely incidental — timing, the General Data Protection Regulation comes into effect on the 25th of May. From this point on, any business collecting data in Europe would have to abide by these rules.

What did this do to the internet?

- The word cookie took on a new meaning — suddenly websites had to start asking us if it was okay to put them in our browsers.

- Many organisations and websites got it wrong, of course, and the fines started rolling in.

- The general public became slightly more privacy aware in general, most likely because of the unfortunate rise of intrusive and confusing cookie banners on nearly all websites.

This regulation is of course one of the most important events in the last decade of data privacy — it’s a signal of where we are and where we’re going, and it’s changed the way companies (old, new, non-existent) do business.

2019

♻️ Facebook ‘pivot to privacy’

In a scramble to maintain user trust, Mark Zuckerberg baffled his stakeholders by announcing a sudden change to his business: that he would now shift his focus to privacy, with every Facebook product. Changes that would soon roll out were things like:

- Strong enhancements for groups and private messaging to put emphasis on private interactions, as opposed to the bulletin-style announcements of the news feed.

- Reducing permanence: basically Instagram stories… but on everything.

- Interoperability: which is the merging of Messenger, WhatsApp, and Instagram messaging.

These three things don’t necessarily have anything to do with putting privacy first. Essentially, all Facebook did here was change their messaging, and not much else.

🥊 Antitrust fight begins a call to break up big tech

Around the same time as Zuckerberg’s above announcement, the world finally starts to get tired of how so much power seems to be centralised to only a handful of big companies.

- Elizabeth Warren, a US presidential candidate writes this piece calling to break up Big Tech.

- Chris Hugh’s, a co-founder of Facebook says we should break up Facebook, saying that “Mark’s influence is staggering, far beyond that of anyone else in the private sector or in government.”

- All 50 US states begin an antitrust investigation into Google.

- The idea to break up Big Tech completely transcends partisan politics, because both Alexandra Ocasio-Cortez and Ted Cruz — two American politicians who couldn’t be further apart on the political spectrum — agree it needs to be done…

The anti-trust laws in place to regulate this sort of thing also seem to be wildly out of date — they were written back when monopolies were being built from products of the industrial revolution; like the railroad. Many believe that we need new laws to help us through this other kind of revolution: a technological one.

2020

What will this year look like after a decade like that? Here are some ideas…

Cookie banners will slowly disappear

Why? Because we won’t need them anymore. Towards the end of last year, we started to see more cookie controls being put into the browser itself. Firefox now block tracking cookies by default, and Chrome have even started adding more control

People are using tools like Company

Another reason why cookie banners will disappear — because the need for better privacy tools has never been greater. You can get a cookie widget right now and even look at new features we have such as Autoblocking, which automatically finds third-party scripts on your site for you.

Soon to be released is also Contextual Consent, where your users can consent to third-party cookies as and when they need to — e.g. the moment they click play on an embedded Youtube video. It’s a neat and simple solution that requires no cookie banner.

🙋🏻♀️ Happy New Year, internet users.