The data privacy space contains many secrets and misconceptions — a lot of the time so that companies can continue to receive healthy torrents of consumer data.

Fear not, user of the internet; watch as I demystify this fiendish and confusing space before your very eyes. Remember, the more you know, the more power you have. That is why four giant tech companies currently control the internet. Here are the five most common misconceptions:

1. All cookies are bad

Since the GDPR, cookies have posed a massive problem for data privacy. Please, I cannot say this loud enough, so this eye-catching graphic will have to do:

![]()

Cookies are not a recent thing by any means, and they were not invented to annoy or upset you. Some quick cookie facts for you to digest with your milk:

🍪 They actually predate the internet, because they are just a simple piece of technology designed to remember information. This was then adopted in the 90s and used in browsers.

🍪 Cookies are quite literally part of the foundational fabric that makes websites function correctly: they are the very thing that you need to make a shopping basket ‘remember’ what you’ve put in it, for instance.

🍪 A pair of binoculars can be used to do some wholesome bird-watching. The same pair of binoculars can also be used to spy on your neighbours. Cookies have a similar energy — just like other tech, they can be used as amazing and devastating brands of online surveillance. This is what has brought forth aggressive tracking techniques in the name of targeted advertising.

What GDPR has done for cookies is both give them a bad name, and make them worse. The GDPR is very long, but the interpretation that publishers have jumped all over is the bit that says you need to get consent for non-essential cookies. I’ll cover how we’ve misunderstood ‘consent’ below, so put that bit aside for now.

The consequences relating to cookies are the unsightly cookie banners that both mess up your user experience, and don’t even work. At the moment, a cookie banner will ask you whether or not you accept cookies, but the site you’re visiting would have already dropped them — that means other companies (third-parties) have an insight on your browsing without you even knowing about it.

So what we have now is a strange and distracting consumer fear of cookies. This series of misconceptions has led to these problems:

- Companies can continue to use cookie banners that do not work, to signal that they are doing something about this whole ‘cookie problem’

- A blanket, unintelligent blocking of cookies leading to the rise of many other tracking technologies that replicate what cookies do, and can’t really be blocked.

- A very damaging distraction from all the other problems, such as…

2. You do not need explicit consent for most things

Besides only seeming to be tied to cookies, there are many mistakes in how most publishers manage data consent. And they are:

Mistake #1 is asking for consent all at once: this is not allowed, and it makes no sense. For one thing, as a user, you cannot be expected to make all decisions about how your data should be handled on first glance of a website. That’s why privacy banners and cookie notices are often ignored — people simply cannot be bothered to engage. A solution to this is NOT to block access to content until a user gives consent. Both these methods are against regulation, and do not allow the user the control they are meant to have.

Mistake #2 is a profound misunderstanding of explicit consent: under GDPR, companies must get explicit consent from users for the handling of data which is not essential to delivering their service. An example of giving explicit consent would be clicking a button that says ‘yes’ in answer to the question, ‘would you like marketing cookies?’

Things that do not count as explicit consent are:

- staying on the site for more than 10 seconds

- browsing to several pages

- scrolling up and down the page as quickly as possible

- reading a cookie banner and ignoring it

- anything else passive like that

Mistake #3 is demanding users to give uninformed consent: there is not enough clear information on what is actually happening when you click ‘accept’. Simply presenting the user with a wall of text showing all the third-parties they share data with does not cut it. Users should be empowered to give informed consent, and this is not it.

Mistake #4 is a mismanagement of consent for third-parties: the use of third-parties is everywhere, and in a lot of cases it’s to enhance or improve a service. Just like putting Intercom on your website so your customers can live chat with you, if they want.

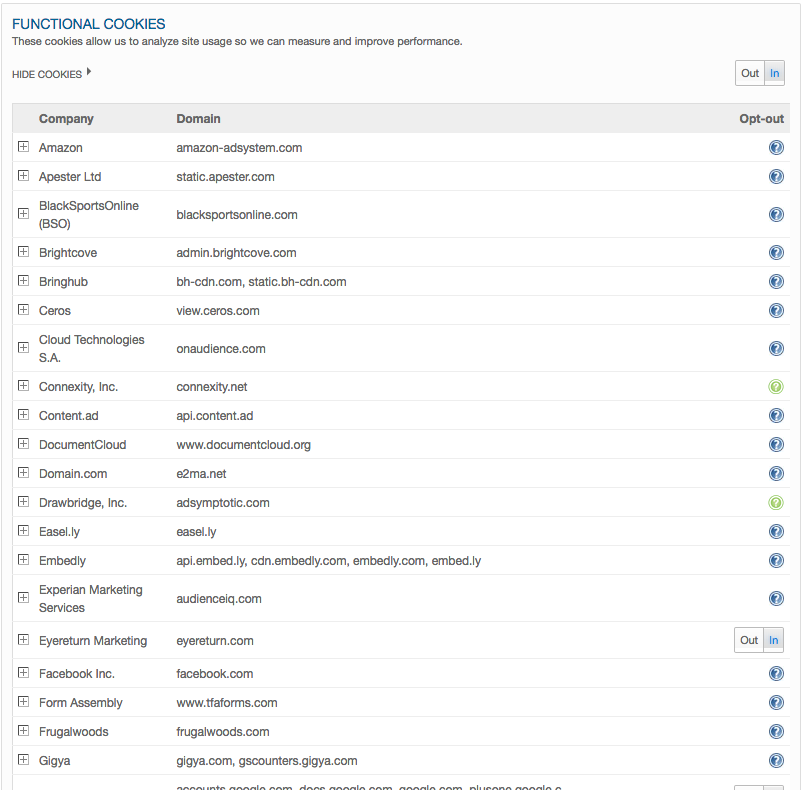

But Intercom is not essential to delivering your service, therefore you have to ask for consent before you can load it up. Intercom is just one example — sites share data with many third-parties, and this is often for advertising. Just like this list of third-party cookies from Forbes; they’ve named these as functional, and therefore do not wait for explicit consent before dropping these in your browser. Collecting data for advertising purposes has nothing to do with helping your site function better.

Mistake #5 is not taking into account the chain of third-parties: the most unfortunate thing about this mistake is that there is no clear way to avoid it right now. As I explained here there is no straightforward way of managing consent for the third-parties of third-parties (otherwise known as… fourth-parties 😳)

E.g. if you use Intercom on your site you need to ask your users if they are okay with that. However, Intercom use Google Analytics. So Intercom need to also need to ask your users if they are okay with that. How do they do that inside a tiny chat widget?

This last mistake leads nicely into the third common misconception…

3. Being GDPR compliant is an objective status

It seems as though the attitude to GDPR compliance is that you either are compliant or not. Incorrect: it’s more nuanced and subjective than that, and there is no shame in not being ‘fully’ compliant.

Striving to be fully compliant to the GDPR is completely unrealistic — this is obvious just from the Intercom example above. There is no way — at the moment — of getting an overview of a user’s data as it flows from one site through a chain of third-parties. All that data processing was never really consented to, so technically none of the companies in the chain are compliant.

This isn’t the regulation’s fault, or the fault of businesses processing data. This is actually a deeper problem, with the current climate of the internet itself. The problems that one might face in trying to be compliant are too nuanced for the GDPR to account for.

It’s also not enforced properly. The threat of being fined is not enough for companies who’s revenue is so large that they simply budget for any fines thrown at them.

So full GDPR compliance is a tough thing to achieve — mostly because it will be hard to even convince anyone that you have.

4. Your users own their data

‘Owning’ data is not a thing — users produce data by using products and services. Those products and services then use the data in a number of ways. So how can the data really belong to anyone?

Nobody owns data; but different people have different levels of access to data, sometimes regardless of who produced it. Having access to a lot of data gives you a lot of power.

You create data for Facebook all the time — they have full access to that data, and that of every other Facebook user. They use this to generate quite a lot of ad revenue, and to amass more power and influence. All through data that they did not produce.

You own the information you share on Facebook. This means you decide what you share and who you share it with on Facebook, and you can change your mind. Taken from Facebook’s privacy principles

This statement is technically correct but doesn’t help. It’s not saying anything new — you’ve been able to control who sees what you share on Facebook for years, and this says nothing about who Facebook are sharing it with. It implies you have some special level of control.

And you do, but that information is often buried. If you actually read a privacy policy (which no one does) on any website, you may see a section called ‘your rights’, and it’s often at the bottom — this is basically an outline of what control you have over the data, and that is what a subject access request is.

Ultimate common misconception: doing a subject access request for the data that a company has on you is not the same thing as asking them to delete it. You are simply requesting to have access to the data. With access to the data, you can then do the following:

- Change it

- See it (not delete it)

- Actually delete it

- Move it to another service — e.g. if you wanted to stop using Spotify and start using some other streaming service with your Spotify data

- Restrict it — that is, tell the product or service that you do not want them using the data in certain ways. Like for advertising.

This is the control you have over data you produce; the fact that this is not common knowledge means that companies are not equipped — or willing to get equipped — to fulfil such requests. In Spotify’s case, this complex work around suggests there’s no way to even transfer data to a new Spotify account, let alone a different streaming service.

So when it comes to data, ‘ownership’ is not a word that applies: it’s about who has access to the data, and what they can do with it — such as users making subject access requests.

5. My business is based outside of the EU — GDPR does not apply to me

The GDPR is a regulation imposed by the EU. However, it still applies to you, even if you’re not based in the EU.

Having a .com makes no difference — as long as you have users or website visitors from the EU, you have to follow the GDPR standard for those users.

So just like the whole internet, data privacy is infinitely complex…

There are actually many more misconceptions out there, but these five are the most prominent. These are things that most people — users and businesses — are not fully aware of. In turn, this lack of knowledge is what maintains the status quo which larger, more powerful entities continue to exploit. Understanding these things is the beginning of rebalancing that power.