The GDPR was put in place to protect people’s data — unfortunately some players are finding ways to weaponise it.

Yes, as if GDPR was not hard enough, we have a few bad actors out there making it harder for the rest of us. Many do not have malicious intent, but they definitely working with a gross misjudgement of what the GDPR exists for. In all cases, there are detrimental effects for users or organisations.

Subject access requests: how they went from ‘what’s one of them?’ to ‘how can I use them to irritate you?’

A subject access request (SAR) is where you contact an organisation who may have data about you, and ask to see it, delete it, change it, or any other number of things which I go into more detail about in this other article. Essentially, a SAR is a way for you to exercise your data rights.

The two main issues with SARs right now are that they have a terrible, non-descriptive name that the average user may not understand. The other issue is that many organisations, even this long after the GDPR was put in place, are not equipped to handle them. And it’s via this latter issue through which they are being weaponised.

Imagine you run an e-commerce store with just a few thousand customers. You may only get five SARs a week. You’d need to make sure you get every inch of data about those users (and , package it up in a readable format, and send it back to them within 30 days). This all takes up a lot of resources — it could put an entire department out of action for a day or more.

That baddest of bad actors that we’ve come across are Ship Your Enemies GDPR who’s site is designed to spam enemies with subject access requests. Firstly: who, besides Bond villains, actually has ‘enemies’? Secondly: this is exactly the gross misjudgement that I was talking about. In their FAQ, under why they built this site, the answer is “because GDPR is fucking stupid”.

Mr Lebowski is correct: ‘GDPR is fucking stupid’ is just an opinion…

Mr Lebowski is correct: ‘GDPR is fucking stupid’ is just an opinion…

Interesting opinion, but here’s a fact: even if it’s not perfect right now, GDPR was put in place to help create a world in which user data is handled more ethically.

What Ship Your Enemies GDPR may have failed to realise is that all they’ve done is built a tool that makes it easier to do something which would otherwise be annoying — it’s actually useful, despite the unethical angle they’re spinning.

Giving you control for the sake of control

There are organisations such as Tap and Rightly who essentially do the same thing as Ship Your Enemies GDPR, but with a completely different message: that users should have more control over their data.

The ideas that Tap and Rightly are selling are about seeing who has what data about you. Their approaches are interesting but raise some questions:

🤹🏼♀️ Organisations now receive requests from other organisations (Rightly, Tap, etc) on behalf of the user instead of the user directly. How can an organisation verify whether or not these middle-men are acting in the user’s best interests?

💭 Is making a bunch of SARs even useful? Does the average consumer even care about this? Most of the information you ‘get back’ from an organisation could be stuff you already knew (because it’s about you) or stuff that is totally useless. It’s possible that other makers may find this data interesting to play around with and use to build things but these services are certainly not aimed at engineers.

🧩 In facilitating SARs, is there some stuff they could be missing? Individual control is great, and making sure people are aware of their data rights is a good idea. But these methods do not foster trust, which is what we need if we want to really start thinking about things like data portability and open data platforms.

The takeaway: organisations should be more prepared to respond to SARs, but is flooding them with SARs the right way around this?

Getting compensated for the data you produce

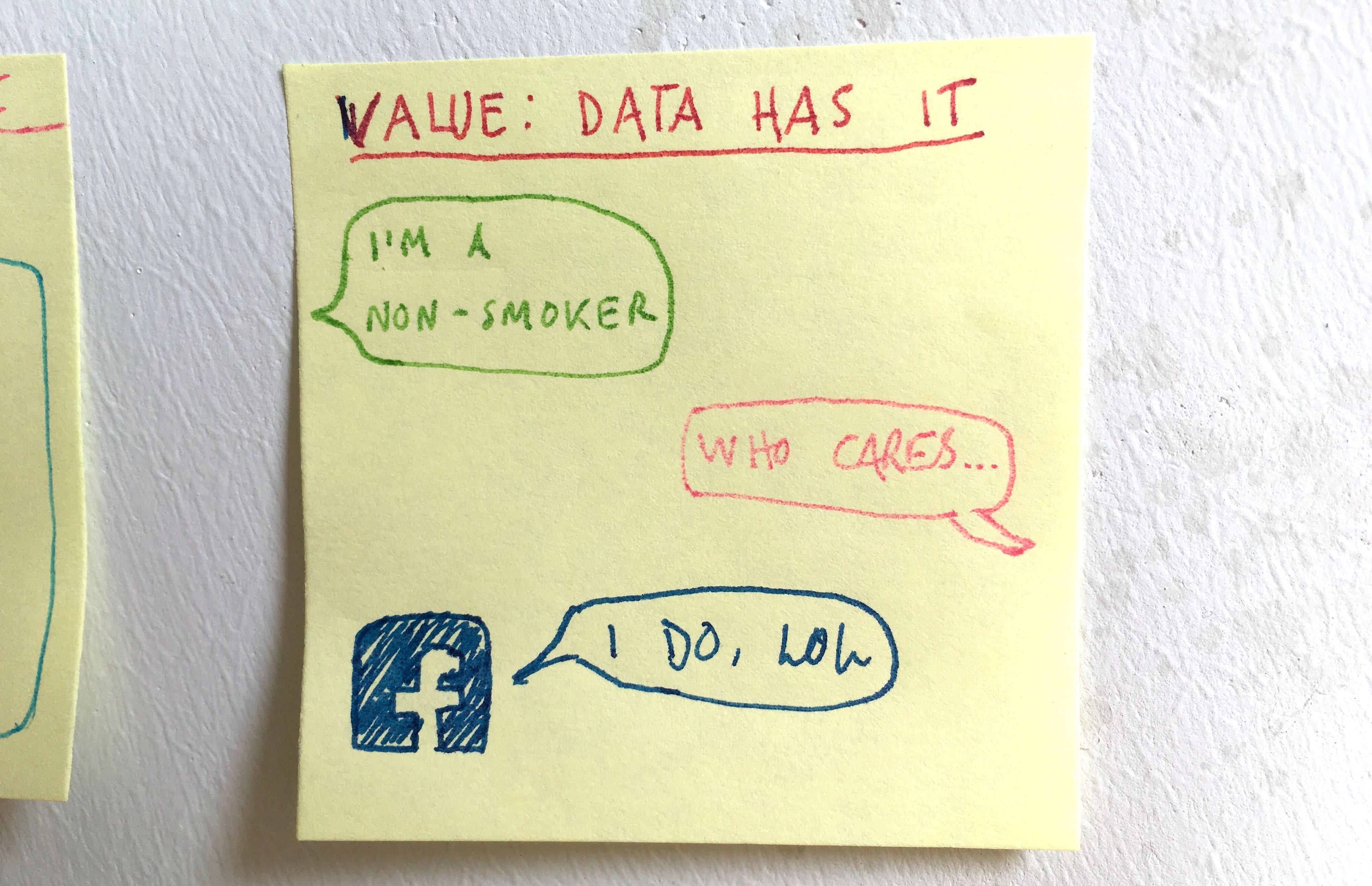

Some services like Datacoup say that the data we produce as consumers has a lot of value, and most of that value is extracted by big tech companies — very little is left for the consumer. That’s because a lot of products and services (like Facebook and Google) are free but they need data to work.

Monetising data is the problem. Monetising it further is not the answer.

Datacoup are right, and data regulations such as the GDPR have really brought these ideas surrounding the value of user data to the fore. Datacoup’s product allows users to turn their data into money. Their thinking seems to follow this logic: ‘if data brokers are making money from this, so should you’.

💸 Do not get distracted by money: monetising data is the problem. Monetising it further is not the answer. This isn’t even a bandaid fix — sure, it might get you a bit of extra cash in your pocket, but does this truly help you get value out of your data?

“It’s about time you earned more than a ‘free service’ for your data […] Datacoup is changing this asymmetric dynamic that exists around our personal data. The first and most important step is getting people compensated for the asset that [you] produce.” Taken from Datacoup website

Saying we should ‘earn more than a free service’ only crystallises user data as a financial product — the data we produce has so much more value to it than just money (one value is to make the ‘free’ services better).

Datacoup’s model solves one problem — it helps you get more value out of your data — but if this trend caught on, it would inadvertently make it harder to explore more solutions that make data a collective source of value for everyone.

So even the GDPR itself can be abused

…but it’s entirely possible that many of the people and organisations abusing it don’t realise they are doing so. What we are seeing here is an extrapolation of tiny facets of the GDPR; a tunnel vision focus on these facets may lead some to overlook key data privacy trends — e.g. in five years, subject access requests may not be necessary any more

It’s understandable that things like this would happen — the GDPR is vast, complex, and open to interpretation. There are those who act maliciously, but there are others who run with ideas that try and help users — and sometimes those ideas accidentally hinder too.