The current rhetoric is that data privacy is something you should care about — but in order to truly keep data private, you actually have to value it.

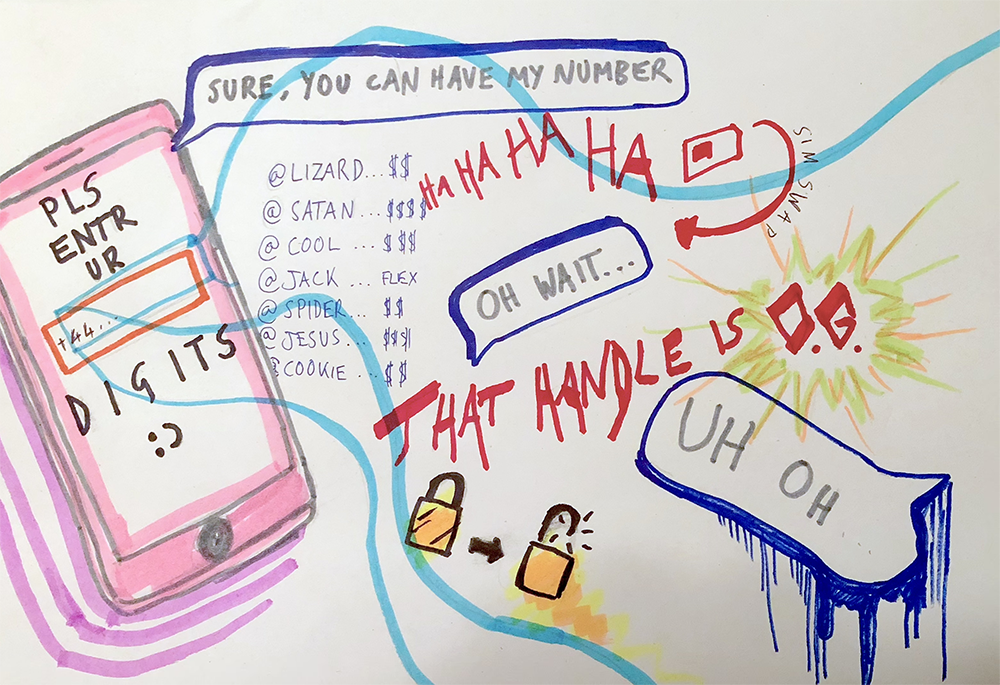

Earlier this year, Twitter CEO Jack Dorsey had his Twitter account hacked into via SIM swapping. How did this happen?

Because SIM swapping is extremely easy: all it takes is one phone call to the victim’s mobile carrier, to request they move their number over to a new sim. Once this is done, the hacker (or Cyber Criminal if you want to be cool), can intercept two-factor authentication texts and get into a social media account by doing a password reset.

The person who hacked @jack was probably not in it for the money — it was likely just a flex. But there are communities who buy and sell ‘valuable’ user accounts. In this episode of Reply All, a woman had her Snapchat account hacked in the same way, and her handle sold for $1500 on a forum called OG Accounts (great name).

Cool handles like ‘lizard’ and ‘satan’ are highly coveted, and therefore extremely valuable. That is why there are communities of teenagers who spend their lives online, bragging about their new Prada shoes (this is not an exaggeration — please listen to the Reply All episode, it is simply life-changing).

Suddenly your phone number, that thing that you type into sign-up forms all the time, has taken on a different meaning — you can see how it has value to other people.

You will never value your own data in the same way that Big Tech does

Mostly because it’s just impossible — data about you is either stuff you just already know (like your name and aspects of your personality) or stuff you can access easily (like your playback history on Spotify).

How do you ascribe value to the various tendrils of data points you produce every day, simply by existing? Let me put it another way: how do you value your own habits and behaviours?

How do you value your own habits and behaviours?

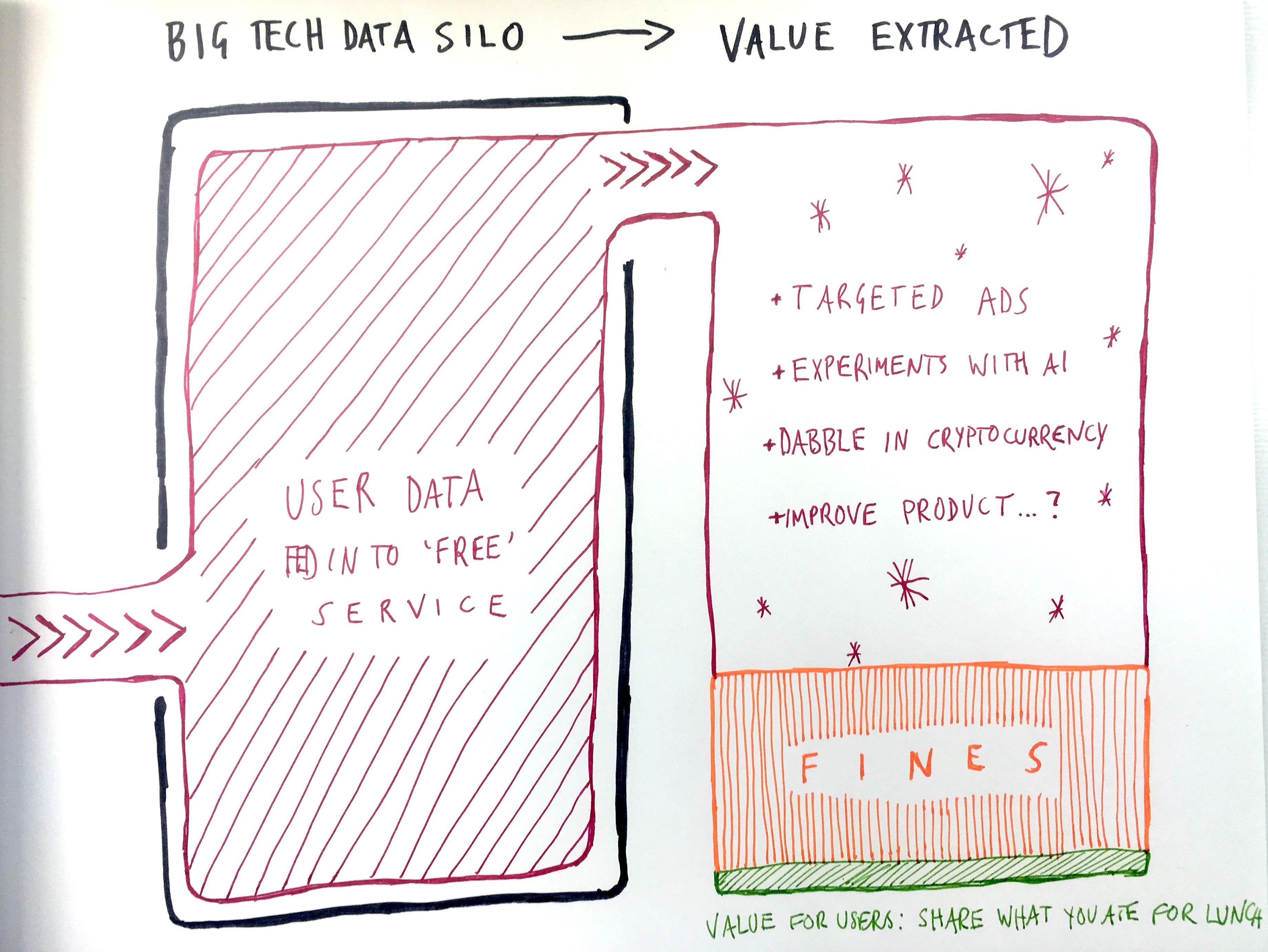

In this piece about behavioural advertising, I outline how ad networks such as Facebook and Google can extract so much more value from the data we give them than we can. We get to Instagram our brunch, while they get millions of dollars to invest into AI platforms and cryptocurrencies. 🙃.

This is why the model works: just like a phone number, the seemingly banal information we siphon into products like Facebook, Google, and Amazon has so much potential value that only they can unlock. Then you get a powerful cycle like this:

Data makes money → money makes more powerful resources → those resources extract even more value out of the data → rinse and repeat.

Although we do get something out these products, the consistent tracking of our behaviours takes away our autonomy: our digital lives are governed more and more by increasingly sophisticated machine-powered personalisation and recommendations.

We get to Instagram our brunch, while Big Tech get millions of dollars to invest into AI platforms and cryptocurrencies.

Maybe this is great because it helps you discover new things. But maybe you hate a machine telling you about ‘something you might like’, and the continual blurring of the line between human decision and machine recommendation. In which case, is all the surveillance and tracking worth it?

A beautifully illustrative example is an app created by the University of Alabama to track the location of students at football games. The university wanted students to stay at games for longer, so offered them points and rewards (like better tickets for big games) if they stayed until the very end of every home game.

Not only is the students’ behaviour monitored, but it’s also changed because they have knowledge that they are being watched. Opting-in to this surveillance has the clean-cut benefit of getting better seats at games in the future. But the cost is having an app govern your behaviour.

What if we get something in return for our data?

The thing that you get in return should be indicative of how much you value that data — and that, in many ways, is the true meaning of data privacy. One of the most prominent common misconceptions about data privacy is that it’s all about keeping your information secret; in fact, it’s actually about how much you value your data.

This is data I gathered about myself over a couple of weeks. What use does it have? How can I value the fact that I watched a lot of Die Hard movies in rapid succession?

This is data I gathered about myself over a couple of weeks. What use does it have? How can I value the fact that I watched a lot of Die Hard movies in rapid succession?

In part one of this piece I asked the whole Company team to choose between living under heavy surveillance in exchange for free products and services or keeping control of their data, while living a fairly inconvenient life.

Essentially I was asking: is the cost of refusal greater than the cost of participation?

Data privacy is not about keeping your information secret; it's about how much you value your data.

Many said that they simply ‘didn’t care’ about being under surveillance, because ‘I’m not that interesting’. This attitude proves my point completely: whether or not your interesting is irrelevant. Companies don’t spy on us for the thrill of it — they collect data, monetise it, and make profit.

The reason why data privacy can be so challenging to manage is because we all value data in different ways. It’s hard for me to ascribe any kind of meaningful value to data points about myself such as my height and my name — this stuff describes me, but I don’t have true ownership over it. I can’t do anything with my first name besides give it to Starbucks to write on a cup.

If we are not equipped to value the data we produce in a meaningful way, will anything ever change?