What do I even mean by ‘regulation’?

First of all, let’s get one thing straight: the internet is amazing. If you’ve forgotten why it’s amazing, simply read this very comprehensive love letter and you will once again understand the infinite, wondrous treasure-trove that is our internet.

But, through decades of growth and abuse, many bad actors have developed some gross standards, resulting in dark design patterns and questionable practices. So, should we be regulating it, and what does it mean to even do that? Regulation comes in all shapes and sizes — good, bad, silly, pointless, etc. To name a few:

📣 Regulating what we can say: this could take shape as content moderation on social media platforms. Someone would decide what you can and can’t say. But who would that be? The platform itself, or some other organisation?

🌊 Regulating what happens to the data we produce: this is what things like the GDPR does (or is meant to do). So yes, we already have some form of internet regulation in place… but is it even working?

🔎 Regulating what we can see: on a small scale, that would be your internet service provider blocking certain websites. E.g. having a parental filter on. On a large scale that would be your government deciding what the entire country can and cannot see. E.g (you may have guessed) China.

I’m going to take an overview of these three areas: how they’ve been tackled so far, how they are connected, and where they could take us in the future.

1. How do we regulate what we’re allowed to say online?

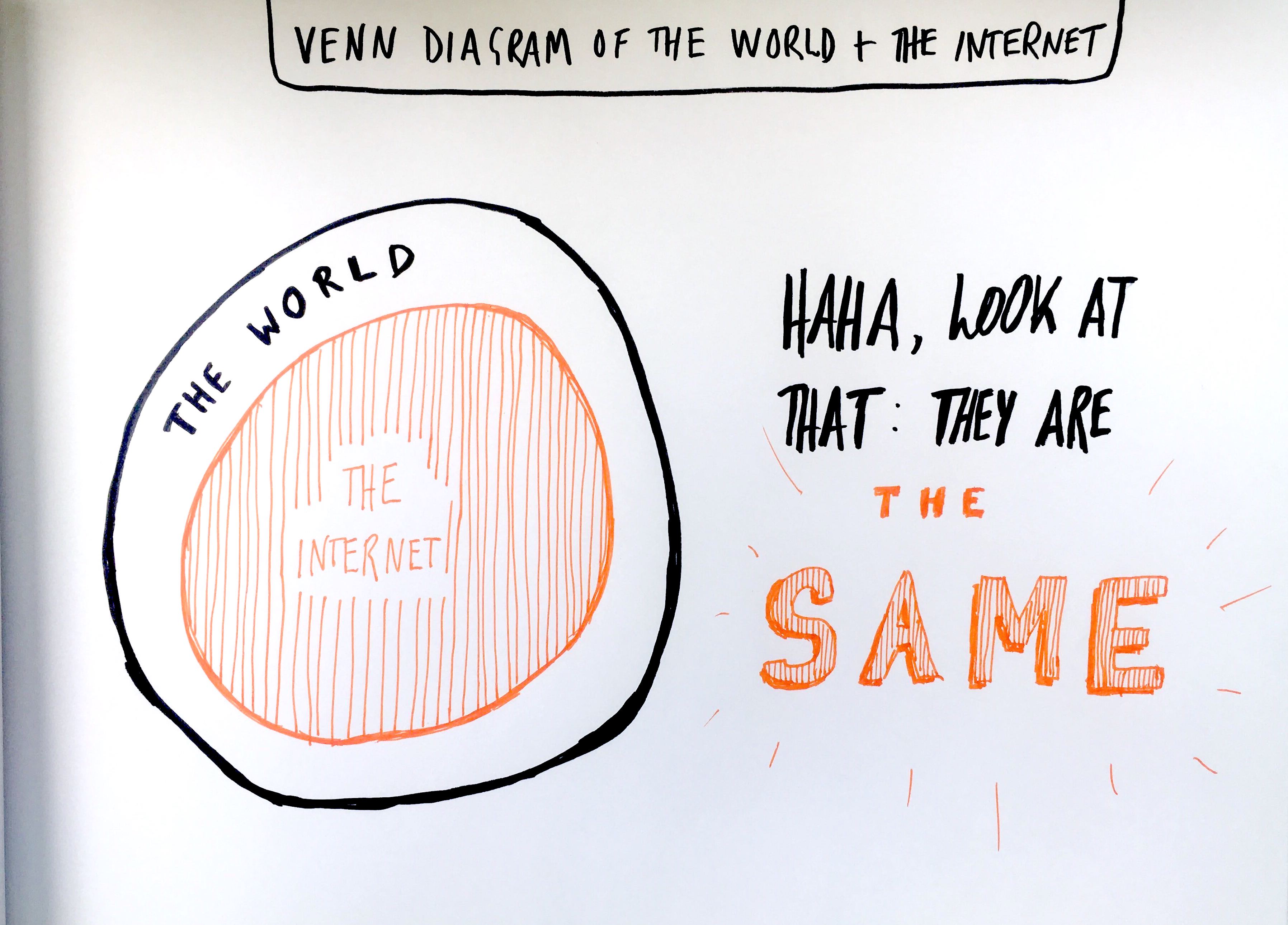

Just as the love letter stipulates, the internet is a free open space full of cheery and enthusiastic people itching to find yet another niche community to be part of. What people routinely forget is that while it may seem like it’s own world, it is actually part of the real world that we live in with our physical bodies.

In the real world, you can find communities, and technically say and do what you want. This is exactly what Alex Jones — raging internet provocateur — did on his Infowars Youtube channel when he consistently and furiously denied that the Sandy Hook school shooting even happened.

The result: the parents of victims were sent death threats from Alex Jones fans. Why was Alex Jones allowed to do this? He’s not — no one is allowed to do this. People were engaging in morally reprehensible and unlawful activity long before the internet came along; the internet is just a new space in which you can do those things.

The internet is just a new space in which you can do morally reprehensible and unlawful things.

There’s a blanket solution, and so far, it’s been to simply ban people like Alex Jones from using their platform, which in this case was Youtube. Twitter and Facebook did the same. Essentially what they were saying was, ‘if you’re going to use our platform to say hateful things, we won’t let you use it at all’. So each platform can decide how to regulate themselves. But is this enough? I don’t know… I guess 4chan wouldn’t exist without this model, so make of that what you will.

A Venn diagram with full overlap…

A Venn diagram with full overlap…

Sure, Alex Jones may be gross but the internet can still be excellent — don’t make me get that love letter out again. Where else would a you be able to engage a community of people in an energetic discussion about imperial measurements? Nowhere, you need the internet for that. So is this a failing of the internet, or a failing of how we humans are choosing to use it?

This how and why the Sri Lankan government somehow missed the point when they effectively ‘turned off’ social media during the church bombings earlier this year. This was in the name of ensuring no more violence occurred. A slightly mindless blanket approach because if people want to do more violence, they will find a way without social media. What’s more, the block left victims unable to contact their loved ones.

A dev here at Company in response to the UK’s white paper proposing regulation of social media

A dev here at Company in response to the UK’s white paper proposing regulation of social media

In April, the UK government perked up about this issue and released a white paper proposing some ideas on how to staunch the flow of hate speech and bullying online. But are governments even equipped with enough knowledge or resources on this to even begin tackling such an issue? And next to big tech, do they even have power to do anything about it?

So right now the internet is a space where you are — technically — allowed to do and say anything. Just like how you are — technically — allowed to smash up someones car with a baseball bat. The only difference is, there is concrete process on how to punish you if you choose to smash up a car.

However, at the moment, there is no effective process in place for wrongdoings online — it’s a conflict of interest for big tech, and governments still don’t know enough to make any meaningful changes.

2. How do we regulate what companies are allowed to do with data?

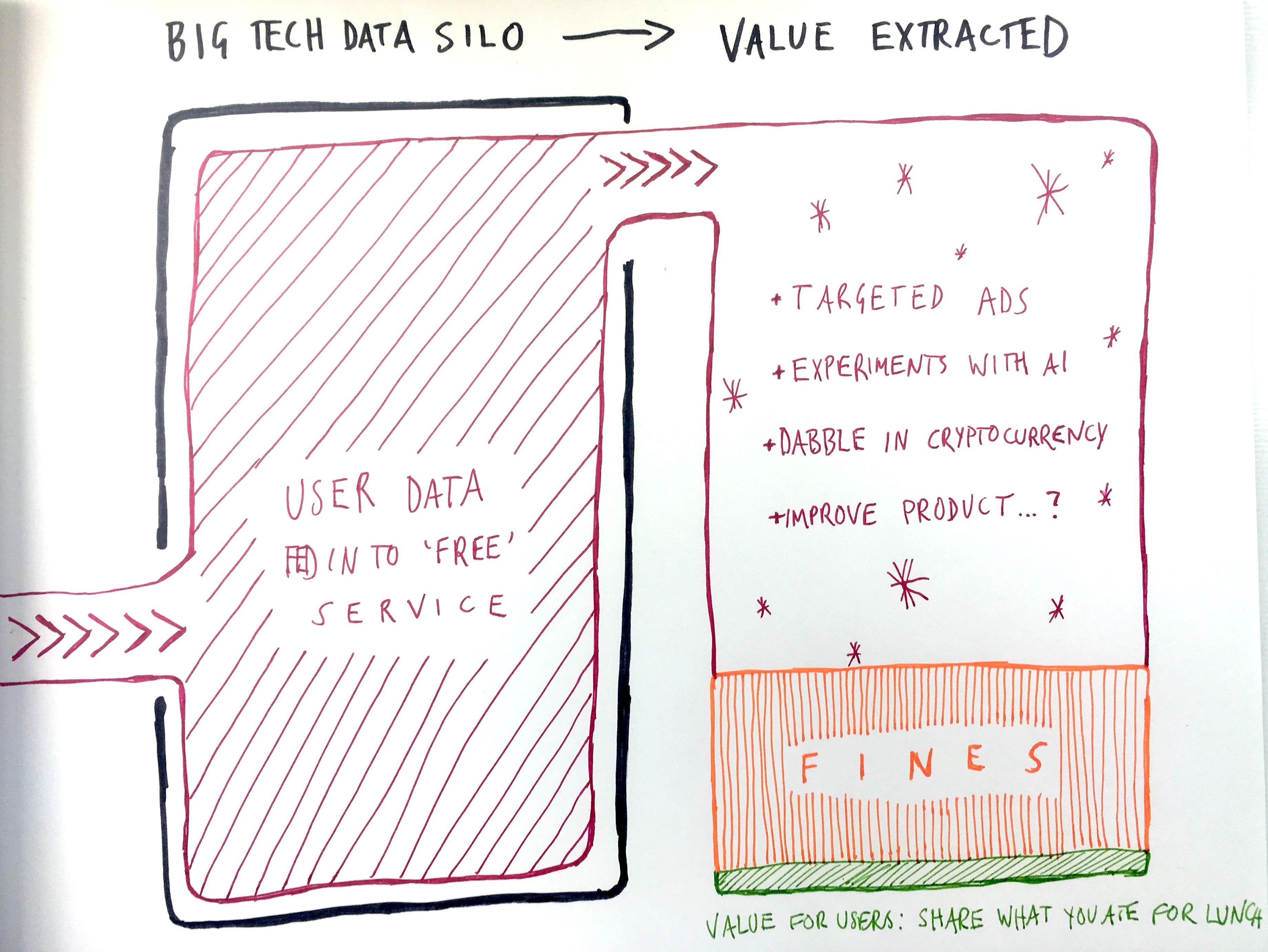

Regulating what the users of the internet say online is one thing, but what about those providing services to the users? At the moment, we’ve sort of gotten to a point where it’s like this:

Free online products exist → people use them, and produce data for those products → makers of the products use that data however they see fit: to improve the product; to make money from ads; to predict what the average consumer will do before they even know themselves 🤔. Now that is something that sounds like it needs regulating.

Good news: the R in GDPR stands for regulation, so let’s start there. To be compliant, an organisation now needs to get explicit permission for collecting user data. This is exactly why cookie banners now exist (I know, yuck). However what this regulation has inadvertently done is focus our attentions on just one area that needs fixing (cookies) , and caused some unfortunate repercussions:

- Cookie banners that ruin user experience, and don’t even work anyway, coupled with a wilful misinterpretation of what it means to ask for consent.

- A blanket, unintelligent blocking of cookies leading to the rise of many other tracking technologies that cookie banners don’t even account for

- A profound mis-categorisation of cookies themselves: some are entirely necessary for websites to function, others are a fantastic brand of 21st century surveillance.

However, there are other repercussions too…

GDPR definitely started a trend

The FTC recently fined Facebook $5bn as means of telling them off. The FTC are an enforcement authority, flexing their enforcement muscles, but does this count as regulation? If the purpose of this fine was to stop Facebook from being so irresponsible with consumer data, it most likely will not work — Facebook’s gargantuan level of revenue means that the only lesson they will learn from this fine is simply to budget for fines. Which they did.

Facebook's gargantuan level of revenue means that the only lesson they will learn from this multi-billion dollar fine is simply to budget for fines

Here’s a thought: if big social media’s answer to someone like Alex Jones is a blanket ban from all platforms, then why don’t we just ban the data-hoarding sites and services from the internet? If only it were that easy. Big tech has amassed an unprecedented amount of power — so much that even they can’t manage it.

That’s how things like Cambridge Analytica happen, and that’s why the Sri Lankan government chose to put a temporary block on social media during the church bombings. The former is a result of the staggering influence of unregulated data processing, and the latter is a result of fear of an great and unknown power.

Now that the GDPR is in place, it has started a very important conversation, and if the good players are loud enough, we can collectively start to make a difference. So on this side of internet regulation, the GDPR is certainly very powerful, but it’s still young. And so are we, in terms of knowing how to use it.

Is the General Data Protection Regulation… too general?

Ah yes yes the GDPR is great and everything but is it a bit too much G for its own good? It’s possible there is a lack of nuance in this particular regulation. The GDPR does not, for instance, account for the complex network of third-parties that connects many businesses. Cookies for third-parties require consent, but how do you manage consent for the third-parties of the third-parties (so… fourth-parties)? You just have to find a way.

Next question: does a regulation really do any regulating if it’s not enforced? At the moment, an organisation can coast through the internet without complying to GDPR, and just hope that they don’t get fined. Here’s a list of all organisations that are fully GDPR compliant:

[this is a blank space where the list should be, sorry]

That isn’t a placeholder for content — fully compliant organisations simply do not exist. This isn’t a dig at organisations, or the GDPR. It’s a piece of regulation that many facets of our dear internet was in desperate need of. It’s not perfect, but luckily it’s not set in stone either — we shouldn’t accept it as a standard, but consider how we might maintain it and make it better.

Regulating data is regulating power

What we’re seeing here is that data = power. Data keeps big tech churning, and all we do is continually produce it for them. So how do we expect they will ever stop growing? Recently there has been talk about breaking up big tech. Law makers have vague ideas to do so, and the co-founder of Facebook even wrote this piece on it.

Data keeps big tech churning, and all we do is continually produce it for them. So how do we expect they will ever stop growing?

As I’ve said before, we currently operate on a model where big tech companies milk consumers like data cows and only leave us with enough milk for one cup of tea a year. The value that they extract via the abuse of consumer data is so great that, yes, of course they can afford to pay the billion dollar fines designed to punish them for that very abuse.

A worthy, but unlikely, solution: make data more portable. This means, data you produce for one service can be transferred very easily to another. So for instance, you could use Spotify for five years but then want to switch over to another streaming service. Spotify have collected a lot of data about you over the years to help them figure out what music you like. Having the ability to move that data to another service gives you a lot more control and choice.

How big tech extract value from the data of others; they get to make a billion sundaes. We get one cup of tea. Seems fair.

How big tech extract value from the data of others; they get to make a billion sundaes. We get one cup of tea. Seems fair.

It’s a worthy solution because giving the consumer the power to freely move data around means that they do not begrudgingly rely on one service. At the moment Spotify is the best out there, so we continue to pump it full of data and it continues to grow. This is how tech giants become giant, and stay that way.

If a Spotify alternative cropped up and had access to the same amount of consumer data that Spotify do, they might be able to do something new and interesting with it, instead of just fading into obscurity while Spotify maintains its large user base. So data portability has the potential to both empower users and breed innovation for organisations.

The value that big tech extract via the abuse of consumer data is so great that of course they can afford to pay the billion dollar fines designed to punish them for that very abuse.

It’s an unlikely solution because the ability to move that kind of data around from service to service means that it would have to be somehow standardised. And that is the bit that requires regulation. Who would dictate the standard? Singapore have already been talking about data portability as a country-wide initiative. But the internet doesn’t care (much) about countries. It has to be bigger than that if it’s seriously going to make a difference.

So this sort of regulation would break up big tech by spreading the dense clusters of data out there across many, if not all, organisations. Instead of just four or five. This would require some large regulating body who’s influence transcends all of big tech put together. Stepping into the next section, you may get an idea of what I mean.

3. How do we regulate what we’re allowed to see online?

Aaaaand here we are… the big one. This type of regulation teeters dangerously between simply keeping things in check and straight up censorship. The latter is what many argue the Chinese government is doing — they have in place what is referred to as the Great Firewall of China: this blocks certain foreign sites and services for the entire country. So apps many of us use everyday, like Whatsapp, are literally not available in China.

Technically, having a fully domesticated, self-contained internet solves many of the problems that I’ve outlined in this article. Think about it:

- Spreading hate online as per an Alex Jones type would not be possible, because there are no such sites where you can even express an opinion.

- Using messaging apps to organise some kind of violent or peaceful protest is impossible because you can only use government-approved chat apps. Which are… monitored by the government.

- There is no tech giant with global power and influence to feast on your data and continue to grow; you only have domestic products and services available to you so the data you produce only goes to those.

Sounds just great, doesn’t it?

Please remember that I did say ‘technically’. What the Chinese government have accomplished here is an unsettling, expert manoeuvre of modern surveillance; citizens do no wrong on the internet, because of the constant threat of being seen. Is this regulation, or just an authoritarian nightmare?

The internet without authority: what you can achieve without regulation

So in the rest of the internet-world, we have very little regulation on what people are allowed to see. That is to say, you can open a new tab right now and probably browse to any website that you want, as long as it exists.

But don’t forget who is controlling that: it’s your ISP (internet service provider; Virgin, BT, etc). They control your speeds, and can control what you see if they want. Most ISPs come with very basic parental controls — that means you can choose to block certain sites you may not want your kids seeing. Therefore, your ISPs need to know what sites you visit, so they know which ones to block.

What the Chinese government have accomplished here is an unsettling, expert manoeuvre of modern surveillance. Is this regulation, or just an authoritarian nightmare?

Now, ISPs are privy to your browsing because they are literally the ones you provide you with internet… they are in charge. They are allowed to block things and throttle speeds and turn off your connection because there is no regulation.

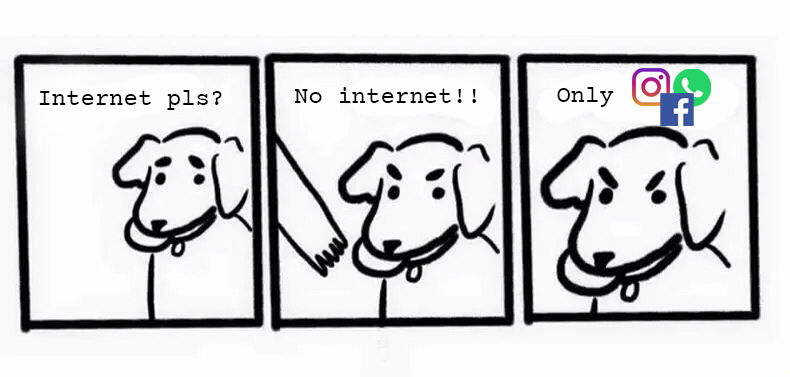

No regulation means that there are no rules on what ISPs are allowed to charge for providing the internet to customers. And that is what brought about data packages like this one, where certain apps and sites do not count towards your data allowance. Which ‘certain apps’? Why, Facebook, WhatsApp, and Instagram of course (to name a few).

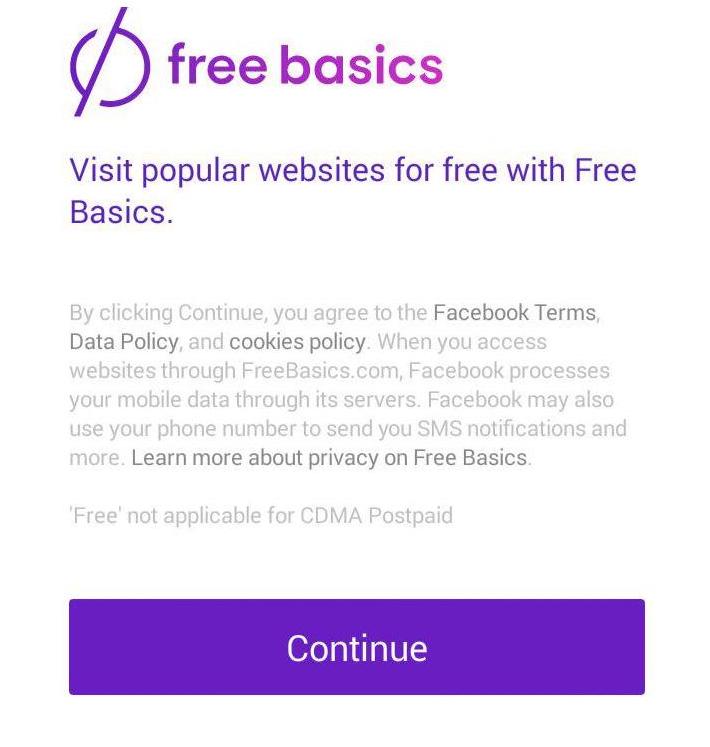

Facebook themselves have taken this one step further: with Facebook Free Basics. This is an app which acts as a free gateway to the internet, providing access to a number of websites and services. This is how Facebook describe it:

Free Basics acts as an onramp to the broader internet, with services such as news, health information, local jobs, communications tools, education resources, and local government information. Taken from Facebook Free Basics homepage

Before you sign up to VOXI and celebrate this free internet revolution, ask yourself this: what are the pros and cons of using a service that is already free on an internet connection which is also free?

The fine print: what it means to use internet provided by Facebook

The fine print: what it means to use internet provided by Facebook

The pros:

✅ If you can’t afford to pay for a large data allowance, you can still use social media, read news, and look at job boards without worrying about it costing more.

✅ Having access to the internet without being restricted by income is liberating, and fair.

The cons:

❌ Increasing access to the internet via only a select few apps only compounds the the problem of continually and dangerously feeding big tech with our data.

❌ Further to that, Facebook Free Basics means that Facebook is the internet service provider for the communities that use it. This completely removes the need for embedding the sneaky Facebook Pixel into every website because Facebook already have a god-mode first-hand view of your browsing.

❌ If only certain bits of the internet are free, and you cannot afford to pay… does that not mean that someone else is controlling what you can see? Is that not kind of like… regulation?

Okay, what just happened? How has a lack of regulation led to something that looks and feels a lot like regulation? I guess if there are no restrictions to speak of, organisations will put in place ones that suit them.

A new kind of ISP, a new kind of regulation

Free Basics has already been adopted in several countries, extending the reach of big tech and tightening their grasp on consumer data. Places such as Ghana and Tanzania seem to have embraced it. Whereas two years ago, India rejected Free Basics as digital colonialism.

India were already colonised once — they aren’t going to go through that again Anosh Malik, developer

Facebook aren’t the only ones bringing the internet to communities that would otherwise go without. Other big tech companies are investing heavily in connectivity: by 2020 Google will privately own three subsea fibre-optic cables. Google also provide internet via a network of low-orbit satellites called Loon. Amazon and SpaceX have similar plans to beam internet from space.

So, if big tech company’s like Facebook, Amazon, or Google can:

📣 Control what we say through content moderation on their extremely popular social media platforms

🌊 Control what happens to the data we produce by using them, and in turn control what we buy, where we go, and how we present ourselves to the world

🔎 Control what we see by becoming the ISP through models such as Free Basics, or even building infrastructure, such as privately owned low-orbit satellites and subsea cables

Then why are we asking if we should regulate the internet? These above three points are exactly what I used at the very beginning of the article to explain what internet regulation is. It looks like the internet is already regulated.

The only difference between what we have, and the heavily surveilled domestic internet in China, is that we are not fully aware that we are being surveilled.

Don’t assume that this paradise of deregulated internet access is so far removed from the highly regulated model in China: the only difference between what we have, and the heavily surveilled domestic internet in China, is that we are not fully aware that we are being surveilled.

While China did this through government, the rest of the internet-verse achieved this via private companies providing us with free (if you mean money) services. This way, they dominated the internet right before our eyes while were Instagramming what we had for lunch that day.

So… is Internet regulation a good idea? Well, we’re already there — you tell me.